Chinese Painter, Who Finds Cubism Conservative, Teaches ‘The Fluidity of the Triangle’ in New York

Ten pupils, of assorted ages and nationalities, study in tenement.

By Joseph Mitchell

Pittsburgh Press Special Writer

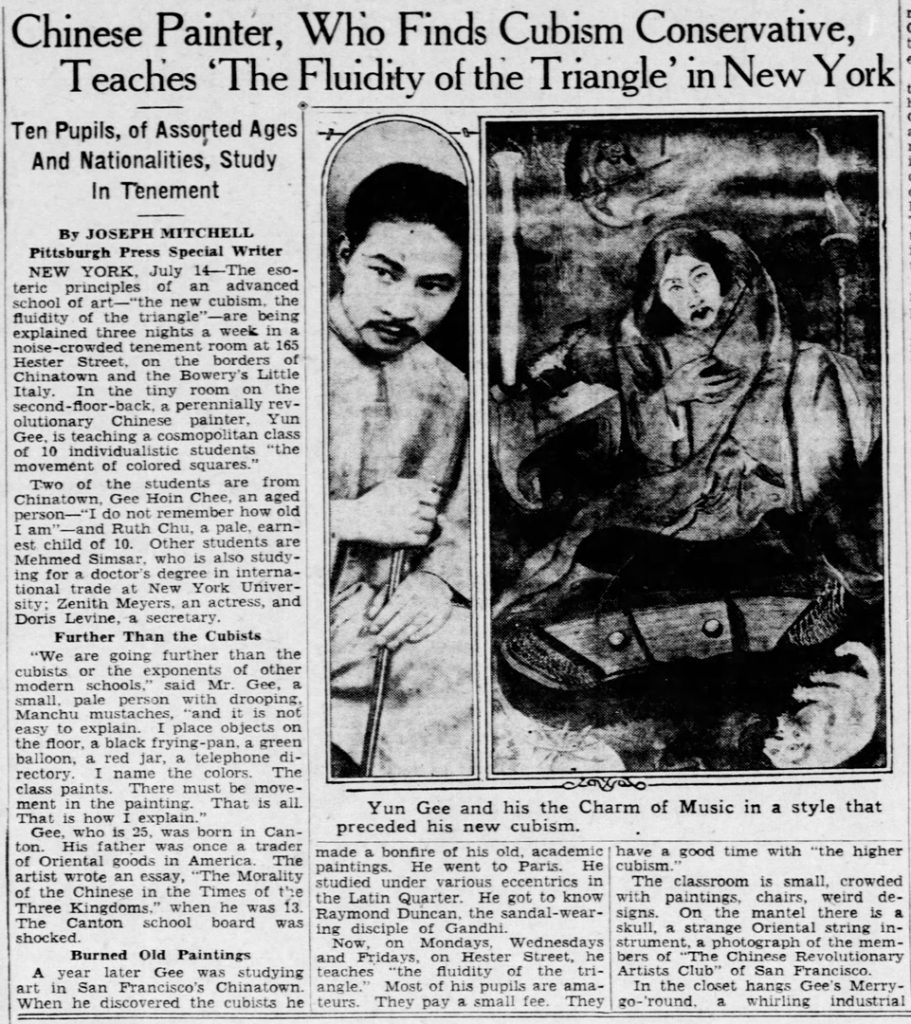

NEW YORK, July 14 – The esoteric principles of an advanced school of art – “the new cubism, the fluidity of the triangle” – are being explained three nights a week in a noise-crowded tenement room at 165 Hester Street, on the borders of Chinatown and the Bowery’s Little Italy. In the tiny room on the second-floor-back, a perennially revolutionary Chinese painter, Yun Gee, is teaching a cosmopolitan class of 10 individualistic students “the movement of colored squares.”

Two of the students are from Chinatown, Gee Hoin Chee, an aged person – “I do not remember how old I am” – and Ruth Chu, a pale, earnest child of 10. Other students are Mehmed Simsar, who is also studying for a doctor’s degree in international trade at New York University; Zenith Meyers, an actress, and Doris Levin, a secretary.

Further Than the Cubists

“We are going further than the cubists or the exponents of other modern schools,” said Mr. Gee, a small, pale person with drooping, Manchu mustaches, “and it is not easy to explain. I place objects on the floor, a black frying-pan, a green balloon, a red jar, a telephone directory. I name the colors. The class paints. There must be movement in the painting. That is all. That is how I explain.”

Gee, who is 25, was born in Canton. His father was once a trader of Oriental goods in America. The artist wrote an essay, “The Morality of the Chinese in Times of the Three Kingdoms,” when he was 13. The Canton school board was shocked.

Burned Old Paintings

A year later Gee was studying art in San Francisco’s Chinatown. When he discovered the cubists he made a bonfire of his old, academic paintings. He went to Paris. He studied under various eccentrics in the Latin Quarter. He got to know Raymond Duncan, the sandal-wearing disciple of Gandhi.

Now, on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, on Hester Street, he teachers “the fluidity of the triangle.” Most of his pupils are amateurs. They pay a small fee. They have a good time with “the higher cubism.”

The classroom is small, crowded with paintings, chairs, weird designs. On the mantel there is a skull, a strange Oriental string instrument, a photograph of the members of “The Chinese Revolutionary Artists Club” of San Francisco.

In the closet hangs Gee’s Merry-go-‘round, a whirling industrial mural painted for a Rockefeller Center competition and exhibited at the recent mural show at the Museum of Modern Art.

The noises of the tenement enter the classroom and compete with the halting, involved explanations of Gee. The small Chinese girl looks at the green balloon and paints a rough green circle. Gee examines it and smiles. He goes into the closet and returns with a portrait of himself by his wife, the Princess Paule de Reuss, who lives in Paris. The students are not bothered by the noises made by radios, whimpering babies and children playing in the street.

Gee disregards the tenement noises. He is absorbed in his explanation of the new cubism.

“This is the first time an art movement was born on Hester Street,” he declares proudly.

•BACK•