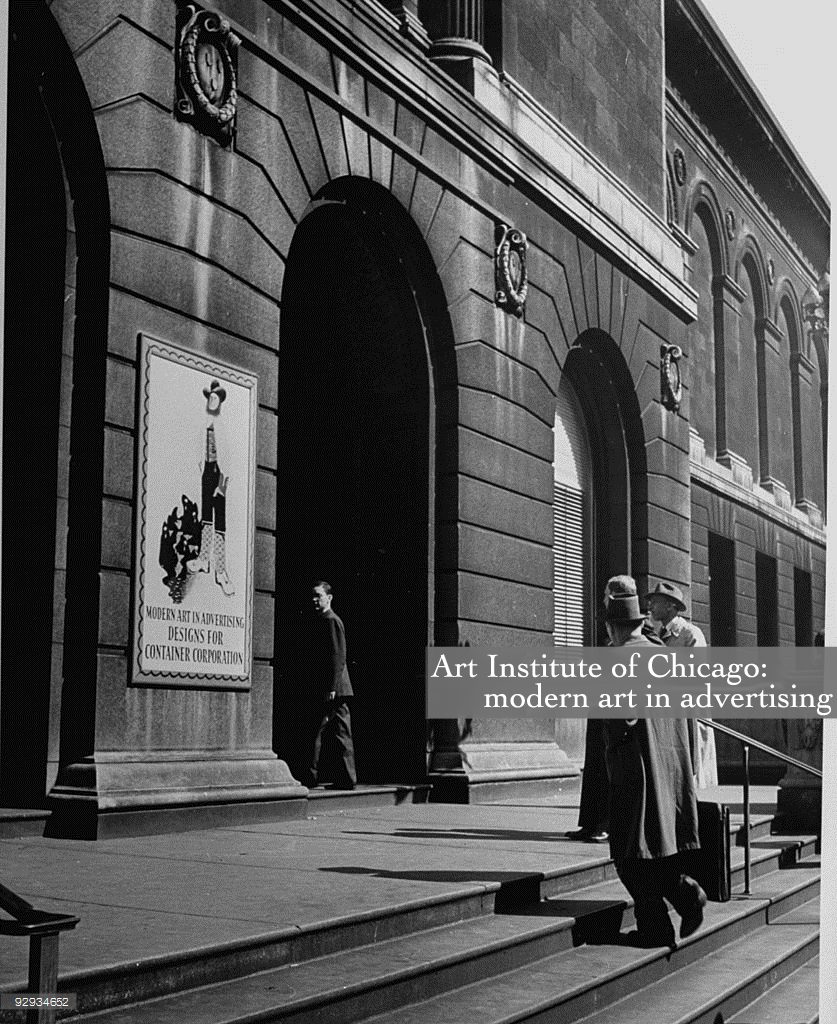

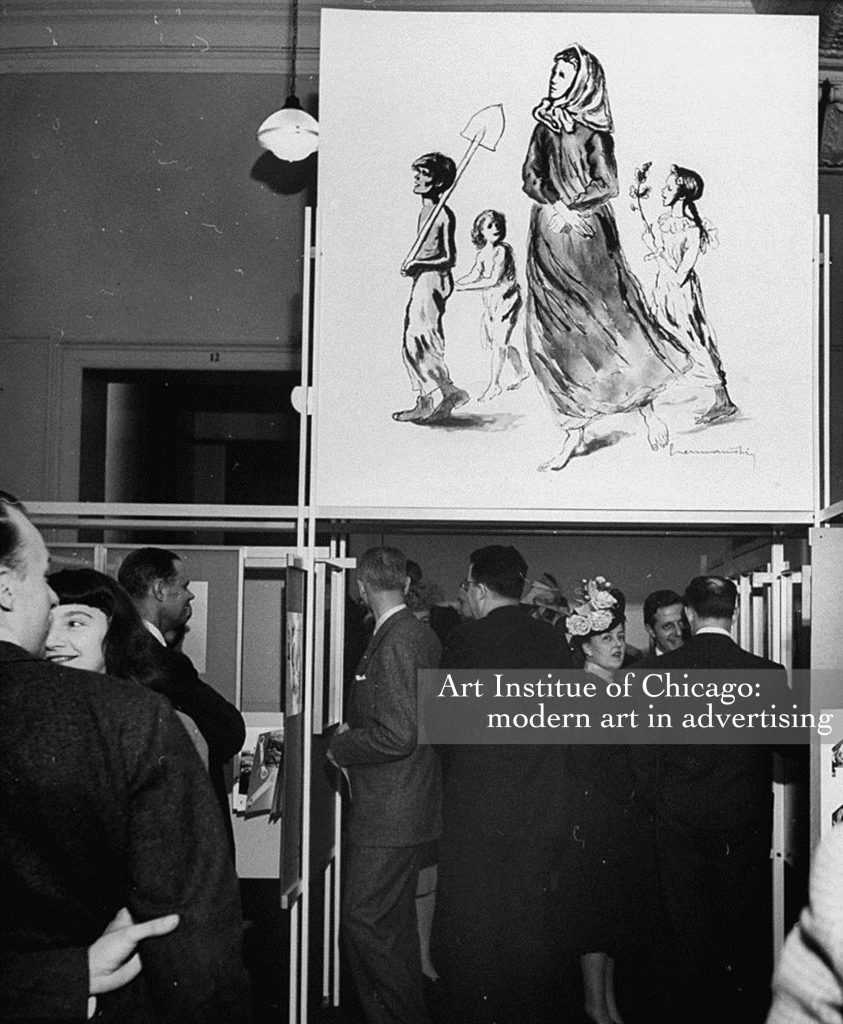

Traveling Exhibition – Modern Art in Advertising: Designs for the Container Corporation of America:

Art Institute of Chicago, (4/28/45-6/24/45)

Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, MI (11/10/45-12/2/45))

Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, (12/18/45-1/20/46)

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1946)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA (1947)

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA (October 1947)

Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR (11/20/47-12/22/47)

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN (11/18/48-1/16/49)

Davenport Municipal Art Gallery (now known as The Figge Art Museum), Davenport, IA (dates unknown)

![]()

Modern Art In Advertising:

Daniel Catton Rich

Director, The Art Institute of Chicago

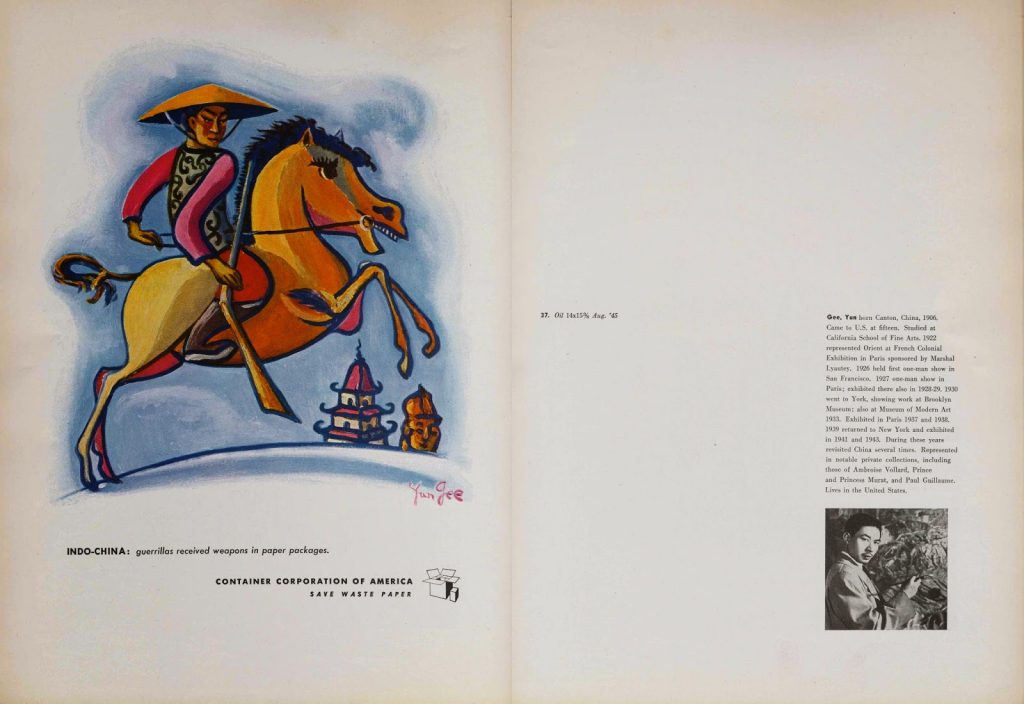

Last year, I asked the Container Corporation to let the Art Institute exhibit eighty-nine designs from its national advertising. For eight years I had watched the Container campaign and it interested me.

Leaders of modern art as well as new talents in the field had been hired to design pages which were often fresh in idea and exciting to the eye.

There is nothing new in the use of modern art by advertising artists. For fifty years some of the boys at the drafting table have been plagiarizing the geniuses of the movement – usually a decade late. The Container Corporation’s originality was to go straight to the inventors – rather than to the copycats – and give them free rein.

How did the exhibit turn out?

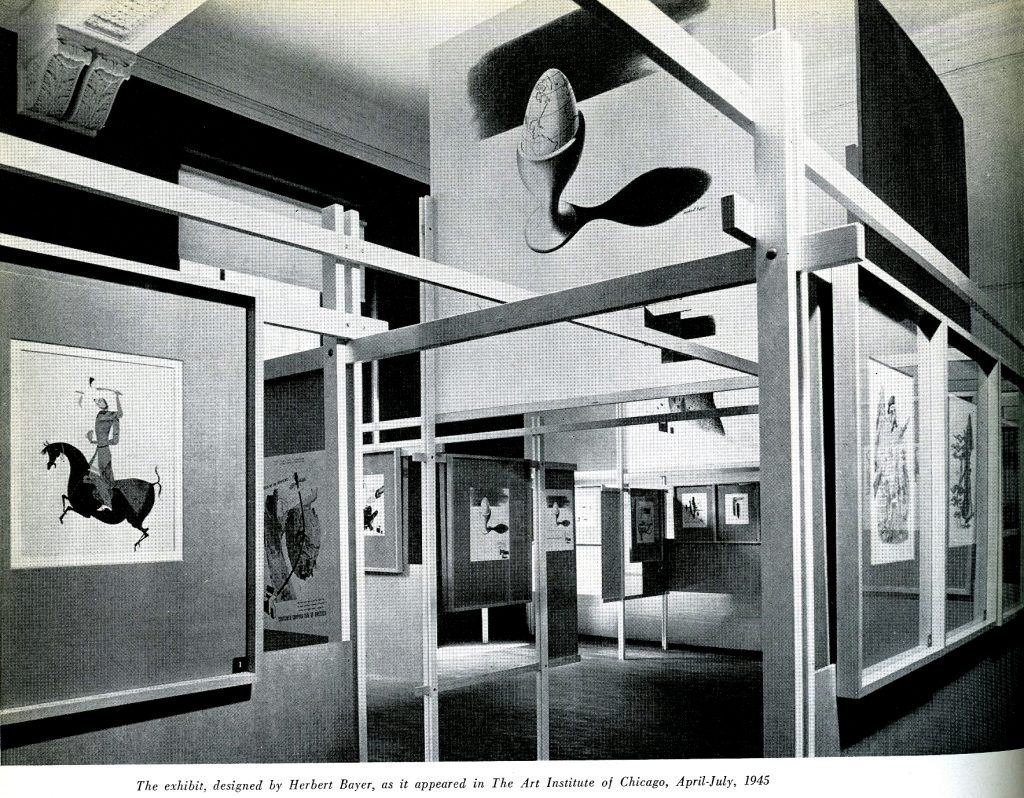

It was a surprising success. Attendance records were broken for the galleries where it hung. That made me believe that people were as interested in the techniques of advertising as in the product advertised.

I admit I was a little disappointed in the exhibit – as an exhibit – but my disappointment was a kind of compliment.

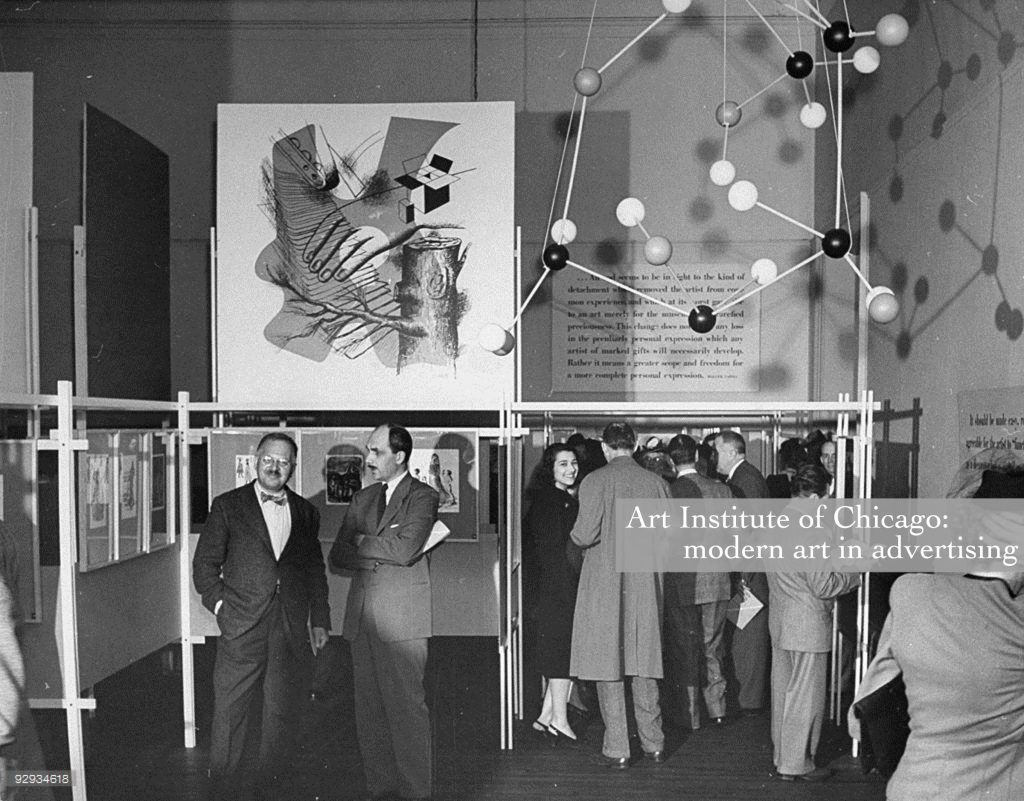

These eighty-nine designs were made for individual pages and when they first appeared in the issues of Time, Fortune, or Business Week, they were electrifying. Hanging together they lost some of their original power which simply showed how well each one was suited to its special purpose.

The more I studied the individual designs and thought over the campaign the more it came to me: This is the most creative program in today’s advertising. It showed several things:

- That modern art has discovered a set of dynamic principles which can be used dynamically in other visual fields.

- That a first-rate artist, once he gets the idea, can turn in a first-rate job in advertising if no one meddles with him.

- That all talk about advertising design being an “American form” or an “American art” is cheap superstition. Some of the most effective pages were by European or Orientals.

In spite of hopeful words I don’t believe that “modern art in advertising” will solve the economic problem of the artist.

Optimists who gloat over the wooing of “art artists” (to use Jimmy Walker’s immortal phrase) by industry would lead us to believe that we are entering a renaissance of art for use and a use for art. They point out that science was once wary of industry but now suspicion has broken down and the two get along happily together. Why not art, too?

A superficial analogy. Modern industry is actually applied science and it needs to return to the pure state constantly for survival. So far much of our industry has yet to prove that it respects or understand or even wants what the artist can give. The most beautiful reproduction of an oil painting by a national prize-winner urging us to swallow more vitamins will hardly usher in the millennium.

All the more reason why Container’s campaign – fresh, contemporary, honest – deserves commendation in a confused world.

![]()

Foreword

From: Art, Design, and the Modern Corporation: The Collection of Container Corporation of America – A Gift to the National Museum of American Art

The history of modern art is full of rebellion – against the academies, Salon juries, art dealers, museums, or others who dared to establish criteria or programs for art. This attitude inspired innovation as artists turned to unsanctioned materials, processes, or styles, but it has also disturbed traditional patters of patronage. Artists have been happy enough to have work purchased on completion, but collaboration with a patron on an artistic enterprise has generally been viewed with suspicion. The modern distinction between fine and commercial art owes as much to the reluctance to serve as the instrument of another’s agenda as it does to new forces of industry, mass audiences, or advertising.

One exception to this rule was found in the philosophy of the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau, which envisioned the artists as an integral and necessary part of society, one whose private imagination is placed in the service of a larger public purpose. Taught to work with commercial and private patron on equal terms toward the common goal of enhancing daily experience, the Bauhaus designer required a broad humanistic background in addition to a specialist’s training.

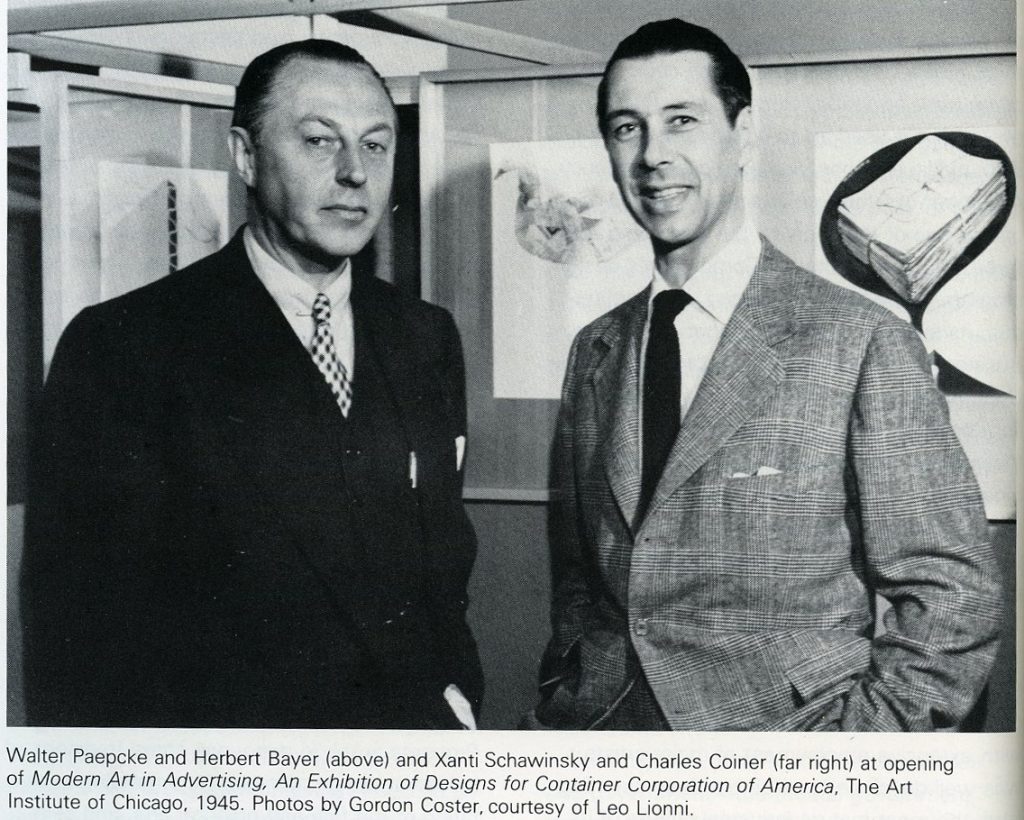

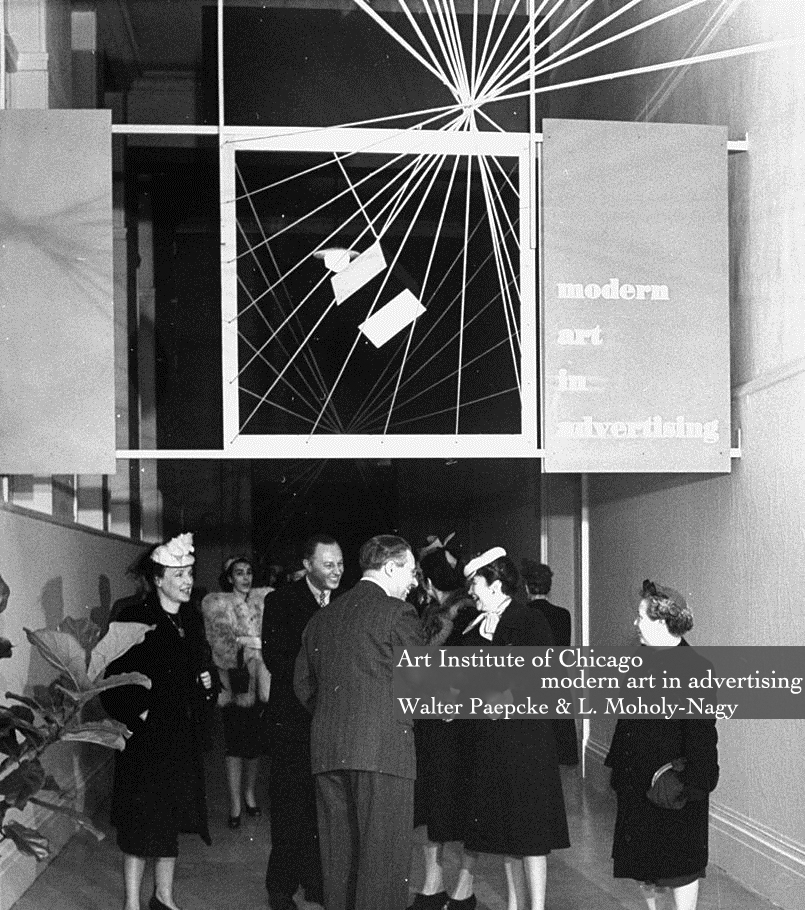

When László Moholy-Nagy brought these principles to the New Bauhaus, a school of design that he was asked to found in Chicago in 1937, he found a sympathetic friend in Walter Paepcke, president of Container Corporation of America. Paepcke’s classical education had barely touched on art, but his intimate knowledge of poetry and music deepened his regard for the creative mind. The Bauhaus notion of the “complete man” dovetailed with the curricular innovations instituted at the University of Chicago by the university’s president, Robert Hutchins, and Professor Mortimer Adler; these philosophies in turn reinforced Paepcke’s admiration for such men as Goethe and Theodore Roosevelt, who fulfilled the ideal of uniting the active and contemplative life. If Paepcke’s corporation succeeded in marrying art and commerce while others effected only a wary alliance, it was because the relationship was built on profound respect. Paepcke knew that the advertising campaigns he began in 1937 enhanced the image of Container Corporation, but his commitment went beyond expediency. He was a true patron, not a patronizer. The emergence of the modern corporation as a significant force in America’s cultural life (at about the same time as the first federal arts sponsorship under New Deal programs) is to a large extent due to the vision of this enlightened humanist.

The designs commissioned by Container Corporation were meant to be reproduced in magazines such as Fortune. A few consisted entirely of graphic layouts that do not survive as independent art objects; others still show overlays and paste-ups, evidence that they were not intended to have a life beyond publication. Gradually, however, Container Corporation encouraged artists to create objects that had independent significance apart from their role in Container’s conceptual program. In the Great Ideas Series (1950-80), artworks commissioned by the corporation were indistinguishable in format and subject from the artist’s other works. Realizing that a fine art collection was forming, the Container staff began to circulate exhibitions drawn from the collection.

However effective the “museum without walls” can be in reaching the widest audiences, photographic reproduction can never do justice to the scale, surface, or color of the original, nor can it capture the sheer élan of viewing a work of art. In this sense, the Container Corporation collection is virginal, now entering a new life full of potential for fresh experience. The intended balance between text and image will inevitably be altered as artworks are seen apart from their original context. The “great ideas” of these objects will emerge in purely visual form and speak eloquently of the thoughts that inspired them. They will remind us to look closely into every artwork – not just these, but all serious art – to discover the ideas expressed by their makers.

Charles C. Eldredge

Director

National Museum of Art

![]()

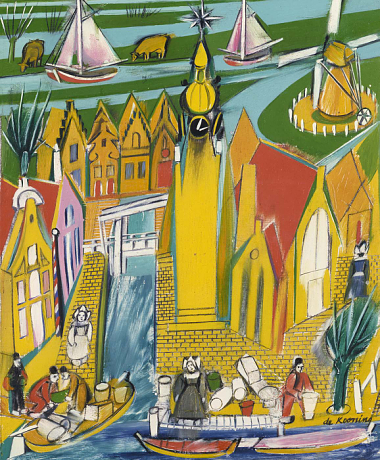

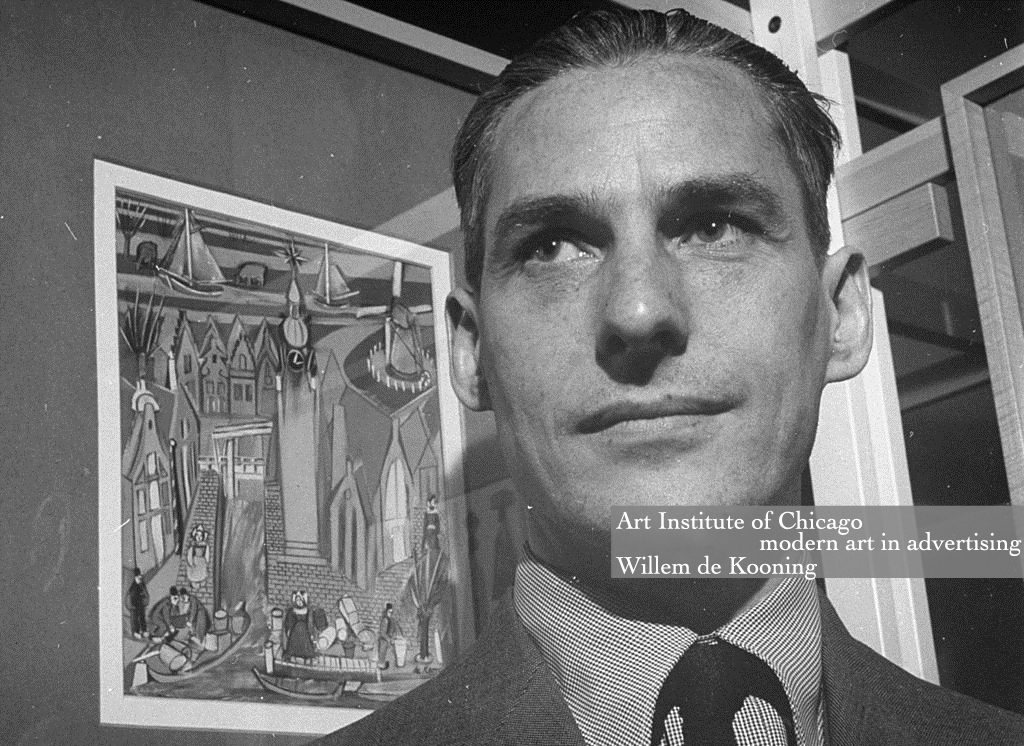

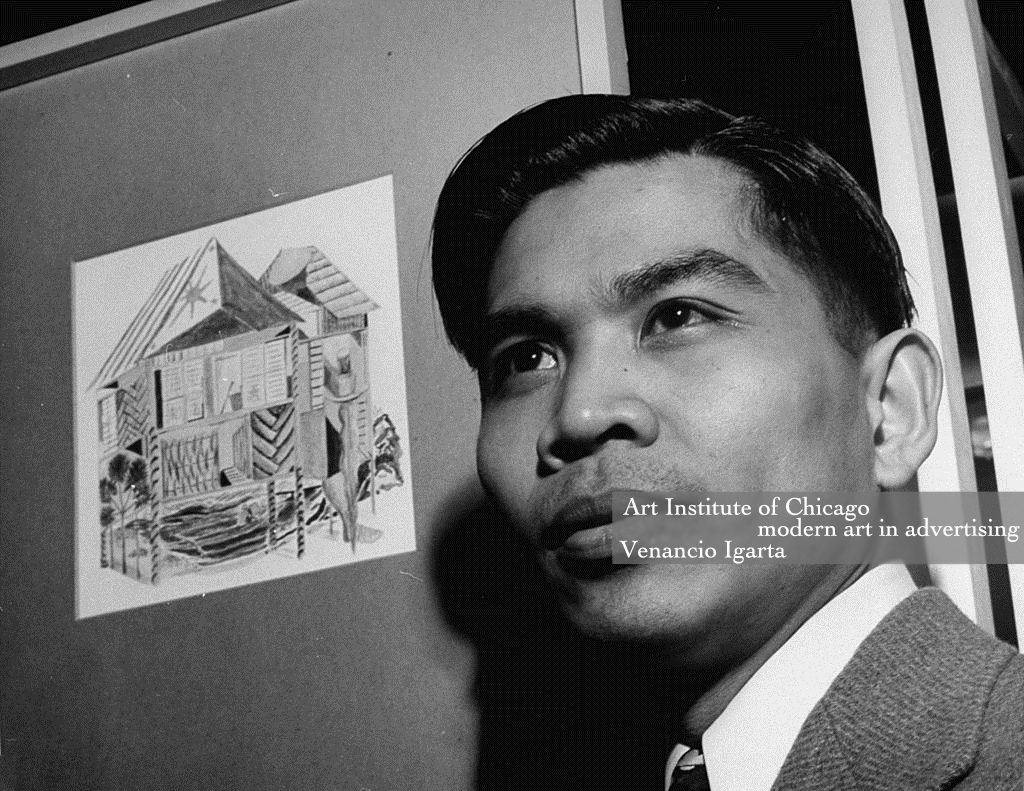

Art Institute of Chicago – Exhibition Photos

The Netherlands

by Willem de Kooning

The United Nations Series

France Reborn

by Fernand Leger

The United Nations Series

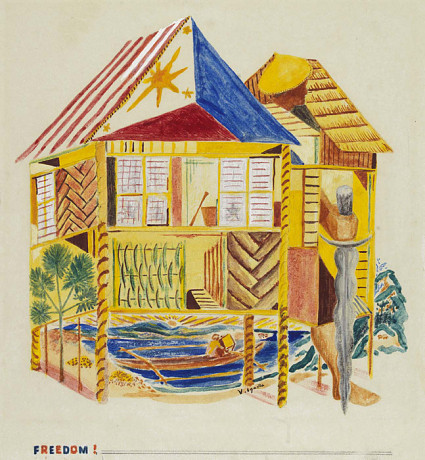

Freedom!

by Venancio Igarta

The United Nations Series

•BACK•