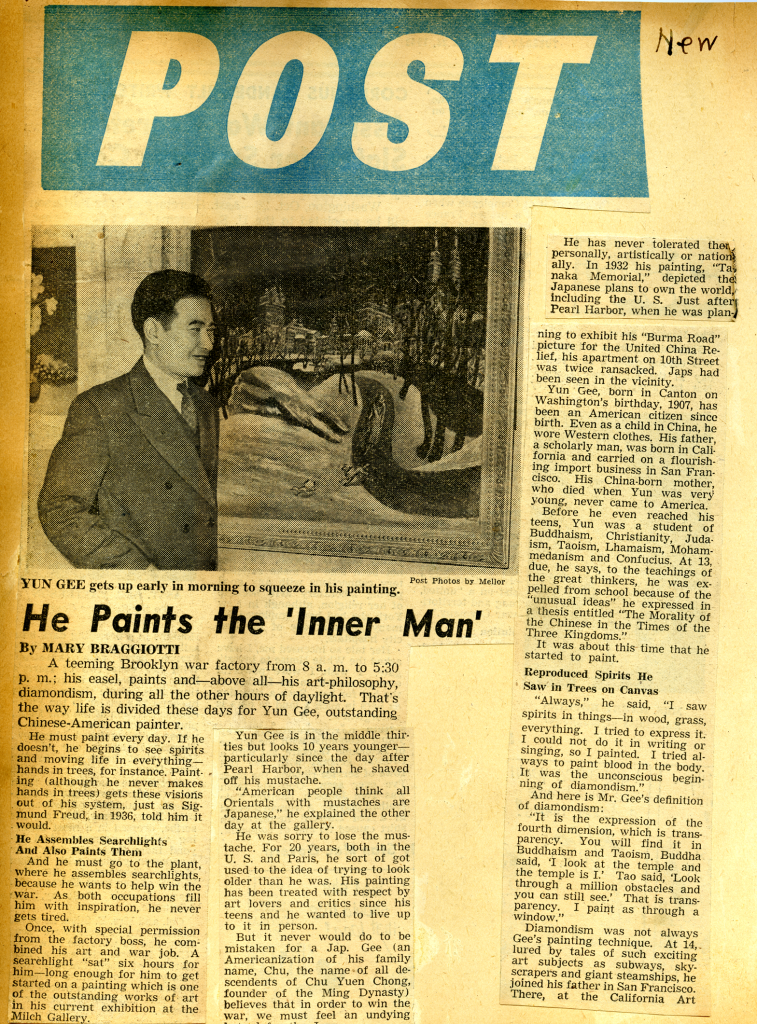

A teeming Brooklyn war factory from 8 a.m. to 5:30 p. m.; his easel, paints and – above all – his art-philosophy, diamondism, during all the other hours of daylight. That’s the way life is divided these days for Yun Gee, outstanding Chinese-American painter.

He must paint every day. If he doesn’t, he begins to see spirits and moving life in everything – hands in trees for instance. Painting (although he never makes hands in trees) gets these visions out of his system, just as Sigmund Freud, in 1936, told him it would.

He Assembles Searchlights And Also Paints Them

And he must go to the plant, where he assembles searchlights, because he wants to help win the war. As both occupations fill him with inspiration, he never gets tired.

Once, with special permission from the factory boss, he combined his art and war job. A searchlight “sat” six hours for him – long enough for him to get started on a painting which is one of the outstanding works of art in his current exhibition at the Milch Gallery.

Yun Gee is in the middle thirties but looks 10 years younger – particularly since the day after Pearl Harbor, when he shaved off his mustache.

“American people think all Orientals with mustaches are Japanese,” he explained the other day at the gallery.

He was sorry to lose the mustache. For 20 years, both in the U.S. and Paris, he sort of got used to the idea of trying to look older than he was. His painting has been treated with respect by art lovers and critics since his teens and he wanted to live up to it in person.

But it never would do to be mistaken for a Jap. Gee (an Americanization of his family name, Chu, the name of all descendents of Chu Yuen Chong, founder of the Ming Dynasty) believes that in order to win the war, we must feel an undying hatred for the Japs.

He has never tolerated them personally, artistically or nationally. In 1932, his painting, “Tanaka Memorial,” depicted the Japanese plans to own the world, including the U.S. Just after Pearl Harbor, when he was planning to exhibit his “Burma Road” picture for the United China Relief, his apartment on 10th Street was twice ransacked. Japs had been seen in the vicinity.

Yun Gee, born in Canton on Washington’s birthday, 1907, has been an American citizen since birth. Even as a child in China, he wore Western clothes. His father, a scholarly man, was born in California and carried on a flourishing import business in San Francisco. His China-born mother, who died when Yun was very young, never came to America.

Before he even reached his teens, Yun was a student of Buddhism, Christianity, Judaism, Taoism, Lhamaism, Mohammedanism and Confucius. At 13, due, he says, to the teachings of the great thinkers, he was expelled from school because of the “unusual ideas” he expressed in a thesis entitled “The Morality of the Chinese in the Three Kingdoms.”

It was about this time that he started to paint.

Reproduced Spirits He Saw in Trees on Canvas

“Always,” he said, “I saw spirits in things – wood, grass, everything. I tried to express it. I could not do it in writing or singing, so I painted. I tried always to paint blood in the body. It was the unconscious beginning of diamondism.

And here is Mr. Gee’s definition of Diamondism:

“It is the expression of the fourth dimension, which is transparency. You will find it in Buddhism and Taoism. Buddha said, ‘I look at the temple and the temple is I.’ Tao said, ‘Look through a million obstacles and you can still see.’ That is transparency. I paint as through a window.”

Diamondism was not always Gee’s painting technique. At 14, lured by tales of such exciting art subjects as subways, skyscrapers and giant steamships, he joined his father in San Francisco. There, at the California Art School, he mastered traditional occidental painting technique, only to renounce it after a short time {he made a bonfire of his 200 early paintings} at the inspiration of Otis Oldfield, pioneer modern painter.

It was in San Francisco that Price and Princess Achille Murat discovered him and persuaded him to go to Paris. So in 1929, he packed up for Paris’ Latin Quarter – thus ending what critics call his “Power Period” and beginning his “Lyrical Period,” which he describes as a form of modernism which, in turn, had been inspired in France by the “chinoiserie” fad of some years before.

He returned to the U.S. in 1931, but was back in Paris in 1936. And after a visit to Freud, his current “Diamondism” or “Life Period” began. That Parisian soujourn, which lasted until just before war broke out, was sponsored by the top-flight art connoisseurs and critics of France. A picture of his is in the Jeu de Paume Gallery in Paris.

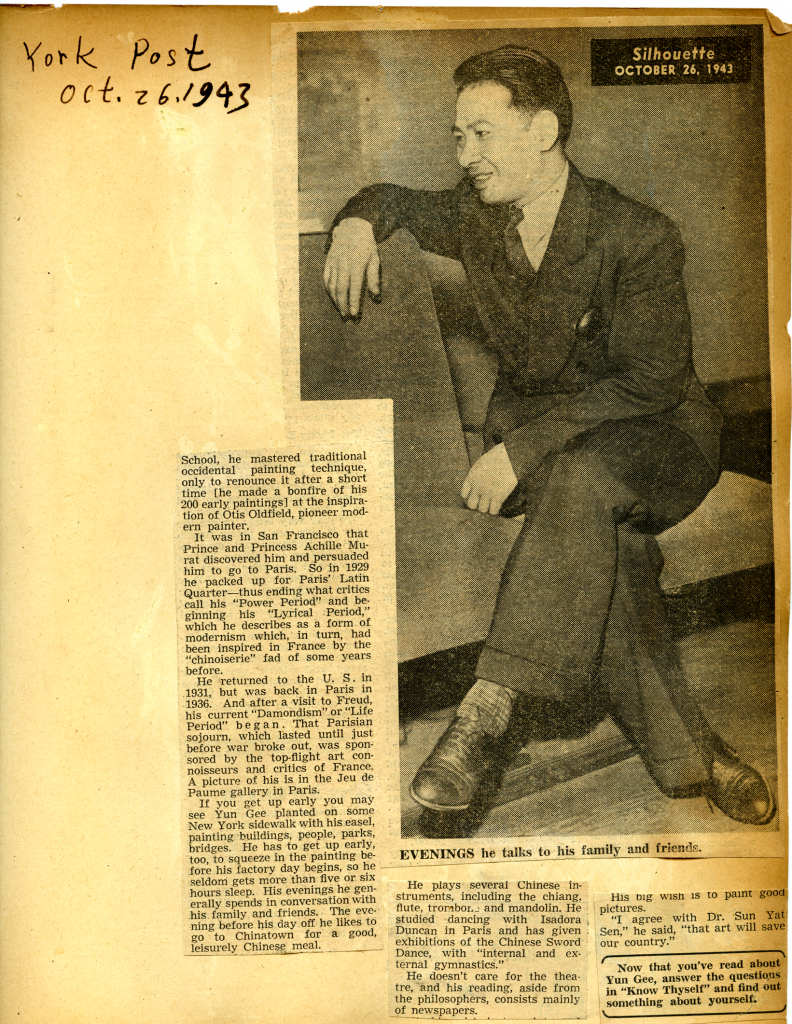

If you get up early you may see Yun Gee planted on some New York sidewalk with his easel, painting buildings, people, parks, bridges. He has to get up early too, to squeeze in the painting before his factory day begins, so he seldom gets more than five or six hours sleep. His evenings he generally spends in conversation with his family and friends. The evening before his day off he likes to go to Chinatown for a good, leisurely Chinese meal.

He plays several Chinese instruments, including the chiang, flute, trombone and mandolin. He studied dancing with Isadora Duncan in Paris and has given exhibitions of the Chinese Sword Dance, with “internal and external gymnastics.”

He doesn’t care for the theatre, and his reading, aside from the philosophers, consists mainly of newspapers.

His big wish is to paint good pictures.

“I agree with Dr. Sun Yat Set,” he said, “that art will save our country.”