Taken from:

Postwar California

Asian American Modernism

By Paul J. Karlstrom

In the effort to determine possible features of an Asian American relationship to modernism (ways in which the various shared experiences of these communities we have decided to treat as one in this book may be reflected in the art), the life and work of Chinese American Yun Gee offers an excellent starting point. I view him as the touchstone for an investigation and discussion of Asian American participation in the modernist endeavor that defines twentieth-century art. In addition, the retrospective lens of postmodernism helps identify earlier tendencies, legitimate aspects of modernism, that appear within an expanded notion of modernism itself.

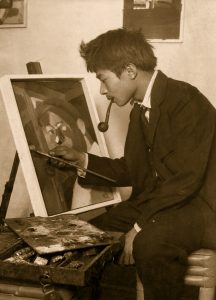

Yun Gee

Yun Gee

1926

Yun Gee functioned within a complex of identity-inflected forces that many white American artists were spared. Race is far from the only factor that informs work and career, but it surfaces in the art of Yun Gee as a dialogue between international modernism and a powerful inclination to give visual expression to personal life experience. Taking into account defining career features from a biographical as well as an art-historical perspective, we can see that modernist personalism, race, cosmopolitanism, and erotic longing, which appear as major themes in Yun Gee’s art, prove enlightening not only to art historians but also to scholars in related fields, including Asian American studies.

Just what is the role of racial identity in the broader picture of American art? How are we to untangle the threads that connect the individual to context in order to better understand the forces underlying creative activity, and, ultimately the art itself? Two other more or less contemporaneous American artists, George Tsutakwa in a specific sense and the African American Jacob Lawrence as a more generalized model, bring the issue of race into focus in a way that is useful in considering the experience of Yun Gee. Tsutakawa, a prominent Seattle sculptor, taught for years at the University of Washington but kep strong connections to family and friends in Japan. He observed that in Japan his work looked American, but in the United Statesthe same work struck many as very Asian. When asked whether he was a Japanese or an American artist, he responded, “I am neither, I am both.” Also a longtime professor at the University of Washington, but one whose heart remained with his community in Harlem, Jacob Lawrence provides a powerful example for a discussion of race in the United States as it affects creative activity. He faced a typical dilemma created by an identity largely determined by his place in a white-dominated world. Simply put, the dilemma consisted of a sense of community solidarity (and, in Lawerence’s case, obligation) set against the individualistic need to function as an independent creative spirit. Part of Lawrence’s achievement was to create, through a uniquely personal modernism based on superficially simple (“primitive” or naïve) forms, a balance between these two competing forces.

From a strictly stylistic perspective, French-derived and American-modified cubism – as influentially practiced by Stanton McDonald-Wright – forges a legitimate link between artists such as Yun Gee and Hideo Date, a Japanese American. But a second point of contact between these two artists may be even more telling in terms of the larger picture. For me, when the personal escapes the restrictive grasp of stylistic formula, we glimpse the individuality of an alternative modernist expression. Among American artists, Marsden Hartley offers the most compelling precedent in this regard: his German expressionist-derived modernist paintings cannot be properly understood without references to the events of his life and the deep longings, reaching back to childhood, that conditioned his relationship to the world.

In Yun Gee and Date we also encounter an insistent self-revelation, bubbling up from interior depths, which can release the work from stylistic conformity. With these two artists, eroticism and nature play significant roles, especially in works like Date’s untitled pencil drawing of 1947 in which female sexuality merges seamlessly with nature in the form of an anthropomorphized tree. A third point of contact also emerges, one that has to do with “Orientalizing,” perhaps not for the legitimate goal of establishing racial identity but for what may be interpreted as a professional opportunism drawing upon that identity and the related stylistic trapping that appeal to a taste for the “exotic.” This understandable tendency, one that is found in both artists but especially Date, adheres also to the great modernist sculptor Isamu Noguchi. Along with Yun Gee, Noguchi serves as an invaluable touchstone, and conveyor of background and context, for later Asian American modernists.

Paul J. Karlstrom, former west coast regional director of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, is the editor of On the Edge of America: California Modernist Art, 1900–1950 (UC Press) and a co-editor of Asian American Art: A History, 1860–1970. He is coauthor of Turning the Tide: Early Los Angeles Modernists, 1920–1956 and author of Raimonds Staprans: Art of Tranquility and Turbulence. Most recently Karlstrom wrote Peter Selz, Sketches of a Life in Art (UC Press).

•BACK•