THE NEW YORK TIMES

November 11, 2005

Art in Review

by Grace Glueck

Yun Gee: A Modernist Painter

Marlborough

40 West 57th Street, Manhattan

Through Nov. 19

A poor immigrant from China who arrived in San Francisco at 15, Yun Gee (1906-63) had cultural and political aspirations. For one, he wanted to introduce Modernist trends in Western art to more traditional Chinese painting. He hoped to create an advanced 20th-century style for China that would gain the respect of international art circles, thus calling attention to the importance of the recently established Chinese Republic under the Nationalist policies of Sun Yat-sen. At the California School of Fine Arts, his teacher, the Modernist Otis Oldfield, introduced him to Cézanne’s practice of building a pictorial structure, colored patch by patch, that produced a faceted aspect important to the Cubists who followed Cézanne.

Several strong portraits in the show have this Cézanne look, among them Head of a Man (1927), with its roughly geometric areas of broken color, and a Self-Portrait of 1926-27 that reveals his sensuous face by means of seemingly haphazard but carefully controlled strokes. In 1926 Gee formed the Chinese Revolutionary Artists Club in San Francisco and moved on to a mode that reflected Cubism with a witty twist, like the painting Modern Apartment (1932), whose geometries and sophisticated color contrasts conjure up a woman lounging in a chair next to an imposing telephone that assumes almost sexual significance. It was one of three of his paintings shown at the Museum of Modern Art that year.

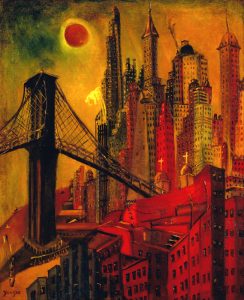

Wheels: Industrial New York (I)

1932

oil on canvas

In this mixed bag of a display, some works show the lyrical influence of Chinese painting, particularly his ink and white watercolor flower paintings and a sprightly number titled Welders: Industries of New York City (around 1933), depicting two men plying their trade in what seems almost a dance. In a more solid composition from this series, Wheels: Industrial New York (1), from 1932, perhaps the strongest work in the show, he salutes the urban dynamics of the city; a bridge, thrusting towers and grubby tenements in a rousing, closely packed composition.

It seems, however, that Yun Gee never really felt at home in the Western world, sensing constant discrimination against him as an Asian. His ambitious plan of bringing Western Modernism to Chinese art remained a dream, and he died disappointed. His work today is interesting for its period flavor.

•BACK•