Western Art Colony Evolves Some New Ideas

A New Greenwich Village Developed in San Francisco Breaks Away From Leadership of the East and Tries Some Experiments in Expression

A humble sister of New York City’s Greenwich Village has found her dwelling place in the romantic artists’ quarter of San Francisco. Here live a group of earnest expressionists, young men and women united in the common cause of art for art’s sake and exercising a unique arrangement in their association. There exists in the coast city co-operative efforts of many orders – co-operative apartments, laundries, tailoring shops and cafeterias. But for the first time on record, young artists have banded together to work and exhibit on a co-operative basis.

The Modern Artists, they call themselves, with a membership which has grown to nineteen since the inception of the arrangement last November. Thus far the consensus of opinion is firm in agreeing that co-operation helps in every way.

The group is to be found in the famous old Montgomery block, which was once the waterfront of romantic San Francisco, where some of the old brick buildings boast a ship’s wreck for a foundation. There, life is flavored with the history of art and the mystery of the foreigners, Chinese, Italian, Greek and French, whose modern shacks and homes adjoin the bock. Old “family style” restaurants, with their fifty-cent table d’hotes, flavor the atmosphere, and cajole the cagier appetites and sometimes meager pocketbooks of the struggling artists. There is found a plumber’s shop, flanked by a sculptor’s studio: a yellow brick building, with little arched cupola, greets it in neighborly fashion. The noise of the repair tools in the auto repair shop vies with the finer sound of the sculptor’s chisel. It is a Bohemia of many orders, irresistible to the sightseer, and offering views of interest from the rough and ready to the artistic.

[…] On the street [summits], where the cable cars clank safely up and down alarmingly precipitous grades, can be seen the inviting hilltops of Russian Hill, with its scenes of inimitable Old World charm. Their slopes, and the hidden scenes behind them, offer numerous and often too distracting subjects for the painter’s brush.

Up in a fourth floor single studio room, one finds a diligent woodcarver putting finishing touches to his bas relief; across the hall, a worker in iron is planning a hammered lamp base. Tale after tale of aspirations and struggles could be unfolded to the listener, visiting from door to door. But, working co-operatively, the owner of each studio feels the value of interchanged kindly criticisms and finds, despite a struggle, a higher goal encouraged, and a real incentive for continuing the co-operative effort.

One large studio room is maintained by the group, where each member holds a two-week exhibition, in addition to several co-operative ones each year. No commissions are charged on the sale of the work, and each lends a hand in helping the other to invite a great number of visitors. The idea of commercializing art is farthest from the minds of this little band.

The group is an interesting one, both from the point of view of varied work and of the different types which compose it. Its little gallery rivals the pituresqueness of similar places in the Montmartre, and the exhibitors are as earnest and enthusiastic as those of Paris.

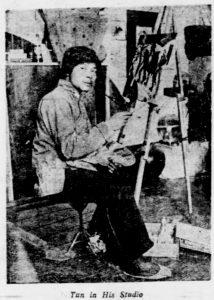

Yun in his studio

Yun in his studio

There is Yun, for instance, a Chinese youth of twenty-one. Yun was born in Canton, China, and brought himself and his desires for expression to our shores only within the past three years. Only for two years did he study English, and then, impatient to get to his better means of expression, his art, he discontinued his schooling. Yun’s father is a poor working man, yet, imbued with faith in his son’s future and ability, from his meager salary, he has financed Yun’s two years of study in night classes at the California Institute of Art.

Yun’s art is colorful and unique. He exhibits his racial peculiarities, bewildering t our Western mind, in his expressions. His is a brilliant temperament, under an unusual simplicity and quietness of appearance. Won over to the cause of Christianity several years ago in his homeland, he has found inspiration for his expression from the Bible stories so alive to him.

Suffering for an ideal is not confined to Yun among this group. There is its founder, Julius Pommer, who combines the qualities of practicality and idealism. Pommer is a tire salesman and can only paint at night and on Sundays. But no trial so simple phases young Pommer. He knows what real trial is. The very beginnings of his desires for art are based on greater tribulation. At sixteen, Julius met with an accident. For one year he lay strapped to a bed. In that year he amused himself by drawing and painting and discovered his talent. He will be partly crippled for life as the result of that accident, but his desire for instruction in art was unimpaired.

For three years, young Pommer studied at night at the California Institute of Art. There, he realized the necessity for individual expression in art if it was to grow among the younger generation. He felt that the newer artists were falling back on the influence of the older ones and not striving to depict the changed expressions evident in the youth of today. The old forms in interpretation did not express the new generation.

To encourage this modern expression, Pommer conceived the co-operative gallery. The younger artists working in seclusion, against odds and unrecognized, were not progressing rapidly enough. It was a simple matter to reach a group of them, and “The Modern Gallery” was born.

In one of his own lone exhibitions, Pommer showed a composition in white, “The Waiter,” a study of skillful speed. Fortunately for his ambitions to become a mural decorator, using oil painting, he has been able to arrange his need for earning a livelihood to a half-day’s session, retaining part of the day for his artwork.

The female contribution to the Modern Gallery has not been satisfyingly large in number, but outstanding in accomplishment. Ruth Cravath has won a gold medal and honorable mention for sculpturing at the California Institute of Fine Arts. She has dug down into solid rock for her creations, a work done by few women. For a large estate in Piedmont, one of the bay cities near San Francisco, she has created the figures for the garden. Her “Madonna and Child,” a liberal interpretation, was exhibited when she was only eighteen. A year before that, Ruth had been studying at the Art Institute of Chicago, where at seventeen, she was the youngest pupil admitted. That had been her home city. But it was back in Alabama, where Ruth’s family had gone for her brother’s health, that she had discovered her desire to mold things by hand. The lavender and yellow clay under the creeks had helped her modeling and her budding talents were encouraged in their growth by her parents, both of whom were musicians.

In her preference for architectural stone sculpturing, she is meeting praising recognition, the modern idea of cutting direct in stone proving a fitting means of her exhibition of her ability.

A Study of Yun by Dorr Bothwell

A Study of Yun by Dorr Bothwell

On the roster of modernists’ names is that of Jacques Schnier, who carves in wood, and does work in ceramics. Jacques is of Rumania birth, but has spent many of his twenty-eight years in America. He has lived in California long enough to have contributed to San Francisco’s work in building a more beautiful city. Schnier has been an architect and an engineer, and in that capacity, has contributed the drawing plans for the First Congregational Church of Oakland, and some figures as a woodcarver for the gardens at Mt. Whitney.

As an engineer, he spent many months in Hawaii, in Maui and Kauai. Later, he studied art for four years. Now he has forsaken his engineering and architecture and is devoting himself to his carvings and ceramics. He can use his architectural experience advantageously, he feels, because the newest skyscrapers are enriched by ceramics – and so youth gets its opportunity.

Schnier’s “Moses” has caused much laudatory criticism, and his “Woman Bearing a Child” has been pronounced most accurate in line.

Schnier has a co-operative critic in Parker Hall, who carves in wood and limestone and forming in line among the modern artists are Dorr Bothwell, who is an impressionistic painter of everyday people and objects; Marian Trace, a female aspirant for laurels as a fresco artist; Wart Montague, who has been famed for his wrought-iron works and others to the number of nineteen. The group expresses a new experiment in co-operation, a new idea in the arts, for self-help and reciprocal aid.

•BACK•