By the time Yun Gee moved to Paris in 1927 as a promising artist in his early 20s, he had already lived on two different continents and experienced emotional adversity. Born in 1906 in Kaiping in Guangdong Province to Gee Quong On and Wong See, he had moved to San Francisco at the age of fifteen in order to join his father, who was working there as a merchant. However, due to the United States’ Asian Exclusion Act, which prohibited Asian women from legal immigration at the time, Gee’s mother was not able to follow suit. It would prove more than a mere temporary separation, as Gee would never see her again. The year before he left for France, he expressed this tremendous loss in a poem entitled Where is My Mother (1926):

That mother of mine, how it tore my heart

To leave her across the sea,

I who was part of her-

She became all of me-

Oh God, how could I speak?[1]

As a result, Gee’s first geographic transition became synonymous with major rifts in his life – both culturally and emotionally. Forced to adapt to his new reality, he spent his early years in the United States trying to carve out a sense of self and a place of belonging. He found the latter within the local art community, of which he became an involved member. He obtained US citizenship and soon began to study painting and drawing at the California School of Fine Arts. Particularly one of his early teachers, Otis Oldfield (1890–1969) and the Swiss-born Northern California landscape painter Gottardo Fidele Piazzoni (1872-1945) aided in shaping his artistic sensibility. In fact, two female portraits of the mid-1920s, Head of a Woman with Necklace (1926) and (Female Portrait) (1927) hint at Oldfield’s Cézanne-inspired compositions, as well as at Piazzoni’s characteristic use of light by contrasting warm and cool colors. In addition to Oldfield, Gee soon acquainted himself with a group of other local avant-garde artists, including Kenneth Rexroth, Jehanne Bietry-Salinger, John Ferren, Dorr Bothwell, and Ruth Cravath, with whom he co-founded the Modern Gallery on Montgomery Street in 1926. While he exhibited his work there, his urge for engagement further led him to establish the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club, where he taught classes in advanced painting techniques and theory. It was against this backdrop that Gee began to develop a unique signature style derived from Cubism that he would later theorize as “Diamondism”. Aiming to explain the intellectual, physical, and psychological coordinates of artistic creation, the latter focused on a rhythmic organization of edges and facets, as well as hot and cold color contrasts. In the late 1930s, Gee explained the need for developing “Diamondism” as follows: “Every sincere painting tries to find an adequate expression of its time, in expressing how people look at things and at what… Diamondism acts as a prism, a one-way glass. It is nothing but a medium, not a cause, but a power. It is up to the artist to use it. Up to the spectator as well…”[2]

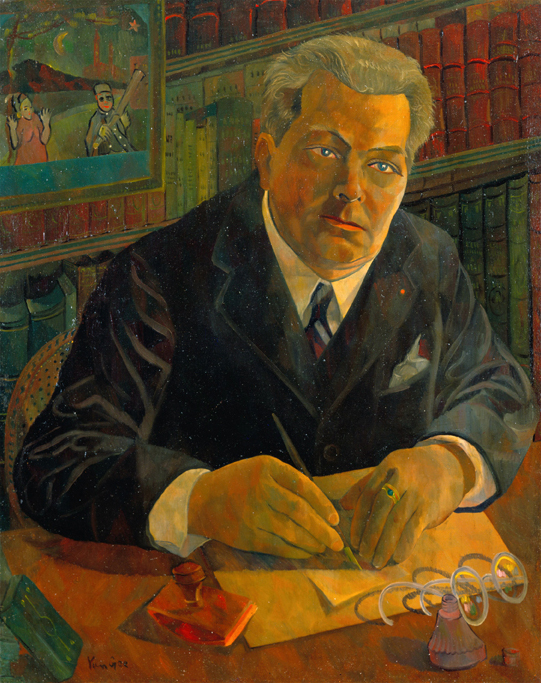

This striking interest in forming a rapport with his peers continued in Europe, where Gee quickly befriended some of the prominent artists of the Parisian avant-garde. Within “seven days”[3] he had his first exhibition, going on to show his work at the acclaimed Salon des Indépendants. In Paris, Gee was no longer the “student” but considered a “master Artist, the philosopher, and young prodigy.”[4] However, it was not until a decade later, after a brief marriage in France, a subsequent move to New York in 1931, where he suffered racial discrimination, the aftermath of the great Depression, and a return to Paris in 1936, that Gee would gain critical acclaim. After having escaped New York’s “apathetic coldness”, he again met various notables of his time, including Sigmund Freud.[5] His portrait of the French writer Édouard Champion (1882-1938) dates from this period. Depicting Champion at his desk, surrounded by his books, his glasses placed in front of him, the work relates to the earlier and less traditionally rendered portrait of the French writer and philosopher Paul Valérie (1871-1945). As a striking pair, both paintings illustrate Gee’s deep appreciation for great intellectual minds. Once again, Gee began to exhibit widely, including at the Galerie à la Reine Margot in Paris and Galerie Lion d’Or in Lausanne, among others.

Perhaps Gee would have stayed in Paris indefinitely, where he “remained in comparative happiness until the clouds of war began to close over the world….”[6] However, in 1939, at the outbreak of World War II, Gee returned to New York, where “the critics still maintained their cool view of [his] work.”[7] Soon, he met his future wife Helen Wimmer, worked for a defense-industry company, and only found time to paint at night. Seated Nude (1942) stems from this difficult time, depicting the female sitter in her full sensuality, albeit against a brooding background. Set against a night sky and dark landscape, the figure manifests as the sole source of light, structurally but possibly also emotionally. The following year, the couple’s only child, Li-lan, was born (1943), but merely two years later, Gee and Wimmer filed for divorce. (Portrait of Li-lan in a Red Chair) was painted around this time, showing the child at the age of two or three years old. Despite her parents’ separation, Li-lan continued to see her father on a regular basis. Visiting him once a week and staying with him once a month, she would occasionally get to see him paint. By the time she was six years old, she would paint on a small easel next to him, at times receiving exercises to solve.[8]

Throughout his career, Gee remained somewhat restless, searching in vain for a critical recognition of his work that would be devoid of racial considerations. Though he had shown his work in New York at the Museum of Modern Art and the Brooklyn Museum in the 1930s and still enjoyed some critical acclaim in the 1940s, his career had begun to fade by the 1950s. As a result, he increasingly succumbed to depression and alcoholism, dying from cancer in 1963, in midlife.

Overall, Gee’s oeuvre embodies a sophisticated fusion of styles and aesthetics rooted in Far Eastern and Western cultures, as well as a yearning for a sense of home. Ideally, the latter would have manifested as a place without borders, free of the concrete shapes that make up countries, continents and political systems; a place that would be free to all and lack the existential concerns that Gee outlined in his poem Worry from 1935:

Those who have been ill will recover

Those who have died may live again

Those who are in heaven may find still another heaven above

As those who are hungry will be full…[9]

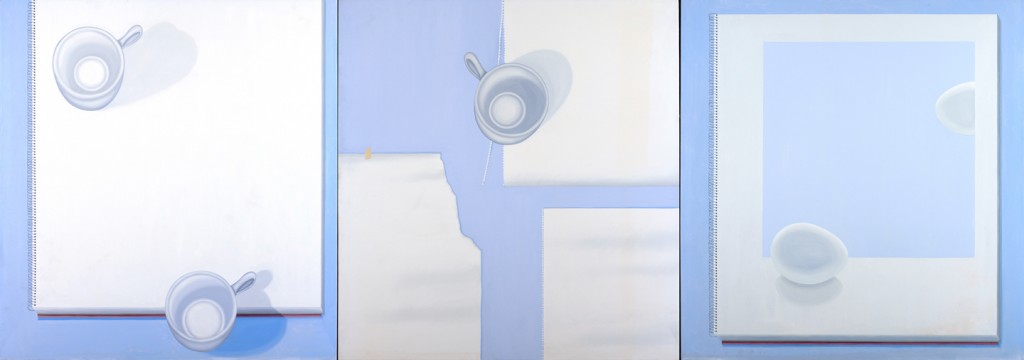

Different in style and execution, the restrained and delicately rendered works of Gee’s daughter Li-lan, reflect a similarly unique thirst for carving out an imaginative space. Though some of her earliest works date back almost five decades, it was a body of paintings from the mid-1970s, featuring still lifes with empty notebook pages that can be counted among her first mature achievements. Paintings like Morning Cup (1973) and Nailed Paper (1973) spring from a time when Li-lan was in frequent transit between homes in New York and Tokyo, where she lived with her then husband, the printmaker Masuo Ikeda. Depicting a variety of torn pieces of paper and open notebooks as if seen from above, Li-lan’s compositions invite both artist and viewer to project their thoughts onto these empty pages. Perhaps the words and drawings that would fill them would tell of travel, of family, or render observations of the mundane. No matter what shape they would take, they certainly would represent a contemplation of the other, the outside, and everything that lies beyond what’s right in front.

Since the 1970s, Li-lan’s paintings and pastels on paper have been characterized by fine delineation. Her figurative forms are set against crisp white grounds, embodying a stark contrast to Gee’s exploration of a somewhat gestural color application. In Gee, different hues are layered in order to form a tapestry of nuance; in Li-lan, color is employed to define clear shapes. Her work is far from mathematical and yet, her sense of balance is rooted in the laws associated with geometry. Occasionally, this affinity becomes overt when finding expression in the parallel lines of a yellow note pad or architectural details.

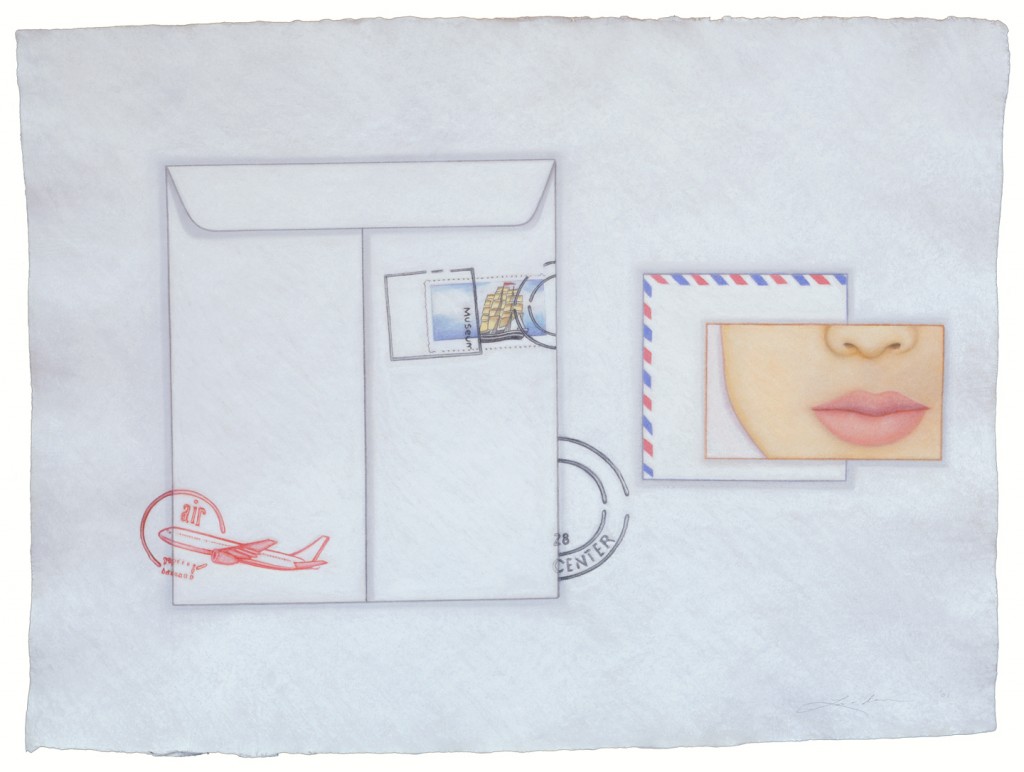

When Li-lan decided to become an artist upon graduating from the High School of Performing Arts in New York, she found inspiration in the works of friends and the Abstract Expressionists. Drawn by the solitude of the artist’s studio, she made a conscious decision not to think about pursuing her father’s profession. Seeking independence, she focused on becoming an artist in her own right and of her own time. It was not until years later, when living with it on her own studio walls that she became intrigued with Gee’s work and life.[10] However, despite all apparent differences, a certain connection can be detected in their works. Like Gee, Li-lan succeeds in imbuing her imagery with a sense of longing. In works, such as Passenger (2001), Tail Fins and Chrome (2000), or Shuttle (2001), letters, postcards, and stamps serve as distilled symbols of cross-cultural correspondence and hint at the desire to connect.

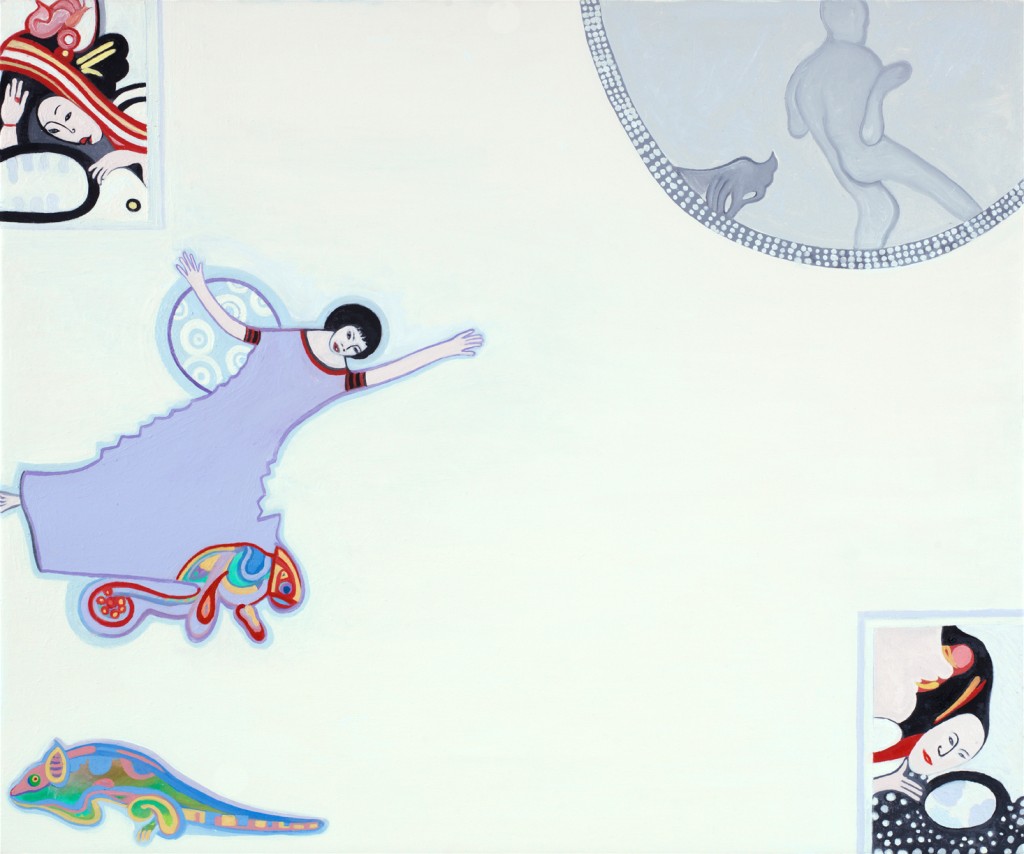

In the past decade, Li-lan’s work has become increasingly narrative, albeit in a nonlinear way. Fabled creatures, ghosts, colorful masks, exotic animals, and architectural details populate compositions, such as Snow Maidens (2015) or Song for Mirror Maidens (2015). At times, eyes will pierce this mysterious fabric, witnessing both the scene unfolding, as well as us. In fact, a painting like Daughter of the Charm of Music (2016) seems to be looking at us as much as we are looking at it.

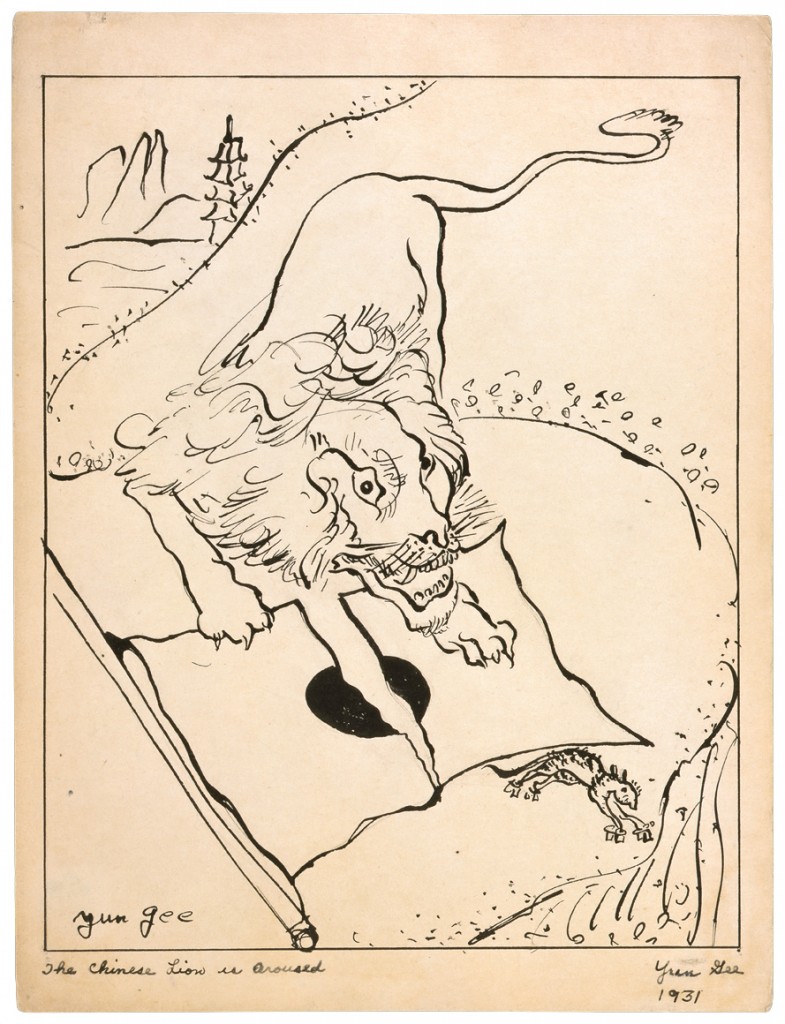

It seems that it is in moments of mythic veiling that the works of Gee and Li-lan can be most closely linked. No matter how different in their overall appearance, the lion in Gee’s The Chinese Lion is Aroused (1931), the old man riding on a water buffalo in his Uncle Size (1942), and Li-lan’s mask in Tracking Honey (2015) have much in common – both in feel and sense of playful awe.

Li-lan’s most recent paintings mark both a departure and a return to her beginnings. Compositions like Spring Song: Flight in the Rain and Dream Song (both 2016) appear simplified in that the shapes have become less detailed and yet, more obscure. In their paint handling they relate to some of Li-lan’s earliest works, such as Yellow Stones (1966), in which saturated fields of color described an utterly luminous landscape. However, it is the abstract shape of the unknown, winged creature in Spring Song: Flight in the Rain that allows for another reference: Georgia O’Keeffe’s A Black Bird with Snow – Covered Red Hills (1946) and Blue, Black, and White Abstraction #12 (1959). In both of these works, O’Keeffe depicted a creature in flight, such as an eagle or crow, albeit abstractly and by means of contrast. The same applies to Li-lan’s latest paintings, in which life manifests abstractly in the form of motion, contrasted by the stillness, solitude and crystal-clear void of its surroundings.

To view works by Yun Gee and Li-lan side-by-side, allows the viewer to imagine a fervent dialogue between two immensely skilled artists, two differing perspectives, as well as father and daughter. This complexity makes for a discovery of multiple layers, ranging from formal expression and diverse content to embedded biographical references. Li-lan’s oeuvre was never conceived as a response to Gee’s work, which stemmed from and remains rooted in a different period. In fact, it is an impressive achievement that her vocabulary reflects a sense of generational progression. Though not without reverence for her father, we find in her work the ambition of a younger artist striving for and ultimately finding her independent voice; one that is more attune to her own time, influences and concerns. Despite a vibrant rapport with many of the artists and intellectuals of their respective context, neither Gee nor Li-lan ever longed to attach themselves to a particular group or to belong exclusively to a movement. It is testament to their strength that both succeeded in carving out a place of their own, formulating positions that are free of the psychological and physical borders established by the expectations and demands of others.

[1] Gee, Yun, “Where is My Mother”, 1926, cited in Lee, Anthony W. Lee, ed., Yun Gee; Poetry, Writings,

Art, Memories, Seattle and London: Pasadena Museum of California Art in association with University of Washington Press, p. 56

[2] Gee, Yun, Diamondism At Last! Or, What It Takes to Make a Good Picture, 1937 (French) and 1939 (English)

[3] Lee, Anthony W., ed., Yun Gee; Poetry, Writings, Art, Memories, Seattle and London: Pasadena Museum of California Art in association with University of Washington Press, 2003, p. 186

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, p. 187

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ratcliff, Carter, The Art of Li-lan; A World Achieved, New York: Hudson Hills Press, 2013, p. 7

[9] Gee, Yun, “Where is My Mother”, 1935, cited in Lee, Anthony W. Lee, ed., Yun Gee; Poetry, Writings,

Art, Memories, Seattle and London: Pasadena Museum of California Art in association with University of Washington Press, p. 56

[10] Cited from correspondence with Li-lan, August 12, 2017

Stephanie Buhmann is an independent writer based in New York City. Her essays have appeared in a variety of international newspapers and art magazines. She has published two books, “New York Studio Conversations – Seventeen Women Talk about Art” (2016) and “Berlin Studio Conversations – Twenty Women Talk About Art” (2017), and is currently working on her third.

Photograph: Marcin Muchalski and Sabrina Vertzman, New York