In 1980 I visited the village of my father’s childhood – the Wong on Li Village in Kwangtung. It was like a dream for me to stand in the home he was born and raised in, and that he had so often told me about. There were the relatives I had known only in my imagination. On the walls hung framed gallery announcements of exhibitions long past that he had sent home to his family. I met the only other artist in Wong on Li, who drank with my father the night before he sailed for San Francisco at the age of 15.

“We always thought Yun Gee would return to China some day. Well, he didn’t come, but now you have. Same thing . . . “ said my Chinese relatives. The warmth of their welcome moved me. I wondered if my father’s paintings would ever return to his homeland to receive the same welcome. Now in 1992, seventy-one years after he left China, Yun Gee’s work is coming to Taiwain. My joy on the occasion of this exhibition at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum is all the greated knowing how happy it would have made my father to come home at last.

The home that he and I shared during my childhood was a small studio in Greenwich Village. I visited him many times after he and my mother divorced when I was two. Even though he was poor, the smell of Chinese cooking signaled warmth and abundance. (To this day, I surprise my American friends with my love for Chinese soup with chicken feet.) Our hours together were filled with the sounds of both French and Chinese as he struggled to teach me both languages. I wrote Chinese character after Chinese character but, regretfully, I didn’t learn them. Neither could I make a sound on the Chinese bamboo flute he tried to teach me to play. We had better luck when we painted together. Side by side at our easels, I worked on the exercises he set out for me as he painted his larger canvases.

Sometimes we would leave our easels behind and go on outings around New York City. He took me to the Zoo, the Botanical Gardens, and our favorite, Central Park. He painted many scenes of the park in the 30s and 40s, but when we were there together he would rent a rowboat and take me out on the lake. I cherish the memories of those special times in which my father shared with me his love of language, music, color, painting and the out-of-doors.

I now understand the moodiness that confused me then. The sauterne bottle that was always within his reach was the source of the erratic behavior that sometimes scared me. He drank day and night, with meals and without, and his ability to function became seriously impaired as time went on. I often think of how alone he must have felt – a Chinese artist thousands of miles from home, living in New York at a time when intolerance and racism was common to the landscape. The comfort that he may have initially found form his bottle of sauterne became one more obstacle he had to contend with, as alcoholism overtook him. In today’s more educated climate he might have received treatment enabling him to reclaim his good health. Instead, his depressions continued unabated, and my confusion concerning his condition persisted into my adulthood. Separating fact from fiction, myth from legend, and misdiagnosed illness from actual illness, has been part of my own journey towards self-understanding and enlightenment.

Yun Gee – 1926

Yun Gee – 1926

My father’s first years in this country were filled with promise and productivity. He studied with Otis Oldfield in San Francisco ( and carried on a life long correspondence with him) and travelled to Paris where he had a brilliant early career.

Later in New York, less well-received than in Paris, his eclectic interests led him to invent and market a 4, 3, or 2 player chess and checker game. He hoped this and other inventions would secure his future. Although his schemes and inventions were proof of a lively, creative mind they never garnered the financial rewards he hoped for. He gave painting classes in his studio and had one inconsequential job after another to survive. His paintings of the 50s were vibrant and expressive but he did not have many exhibition possibilities then. He had a one man show in New York in 1962. This was his first opportunity since 1948. A year later, he died of cancer at home in his studio at the age of 57.

Whatever the circumstances, though, Yun Gee sent money back to China. He gave music and dance performances as well as benefit exhibitions to support the relief of flood victims back home. When I visited his village, even the young people knew my father as the artist who had sent money to help his people.

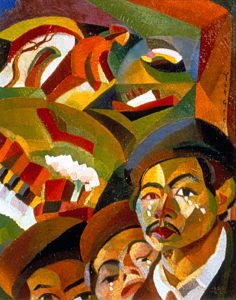

Where Is My Mother

Where Is My Mother

1926

oil on canvas

20 1/8 x 16 inches

The love he felt for his family and homeland was revealed in his 1926 poem “Where is My Mother,” and in his painting by the same name. He pictures himself with tears on his cheeks, and in his poem tells us

I dreamed that I could bring her close,

Created the painter’s art

On the canvas

Mother looking out of the door,

By the mountain road a cart,

A plane in the air,

The ship on the sea,

Could I find my mother again?

How moving it would be for this young man who left his mother at the age of 15, to see his work exhibited so close to home. My father’s love as well as loneliness were transformed on the canvas into shape and color.

As a small child, I saw stacks of paintings in his studio, piled high, turned in towards the walls. I often wished those paintings could move outside to take their place in a bigger world. Just as it would move my father, it moves me that his work is now being celebrated by his countrymen.

Of course, an international exhibition of this scope requires tremendous effort. It was Li Lundin who introduced Mr. Kuang-nan Huang, Director of the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, to the work of Yun Gee. Her enthusiasm and the museum’s tireless effort and conscientious attention have combined to create this major exhibition. They have my gratitude.

February 1992, New York City

Li-lan has exhibited extensively in the USA and internationally, particularly in Taiwan and Japan. Her work is in major public and private collections all over the world, including the Weatherspoon Art Museum in Greensboro, NC; the Parrish Museum in Southampton, NY; the William Benton Museum of Art in Storrs, CT; the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the Ohara Museum of Art in Kurashiki, Japan; and the Sezon Museum of Modern Art in Karuizawa, Japan. She lives and works in New York.

•BACK•