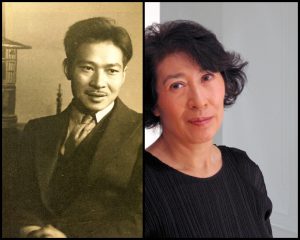

My Father and Nature by Li-lan

I visited my father most weekends. I was merely two years old, as my parents separated, then divorced. His various birds were his beloved friends, and were given free rein to jump, roam, walk, and fly around his studio. He would even take one of his mynas to Washington Square Park on walks, with a little chain around one leg. He adored his birds.

Continue...

I visited my father most weekends. I was merely two years old, as my parents separated, then divorced. His various birds were his beloved friends, and were given free rein to jump, roam, walk, and fly around his studio. He would even take one of his mynas to Washington Square Park on walks, with a little chain around one leg. He adored his birds.

Continue...

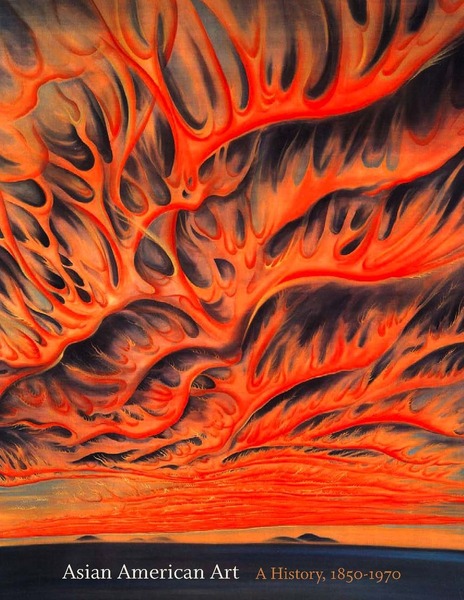

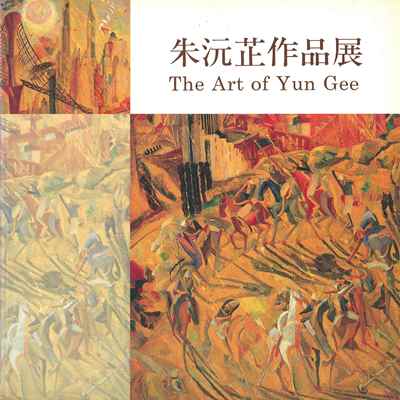

Yun Gee penned “The Chinese Artist and the World of Tomorrow” in the mid-1920s, a few years after settling in America. In it, he proposed two goals for his contemporaries: embrace Western influences in order to make Chinese art more universally relevant for the twentieth century and promote Chinese philosophical principles for the general betterment of the world. It also offers a template for Yun Gee’s career.

Yun Gee penned “The Chinese Artist and the World of Tomorrow” in the mid-1920s, a few years after settling in America. In it, he proposed two goals for his contemporaries: embrace Western influences in order to make Chinese art more universally relevant for the twentieth century and promote Chinese philosophical principles for the general betterment of the world. It also offers a template for Yun Gee’s career.

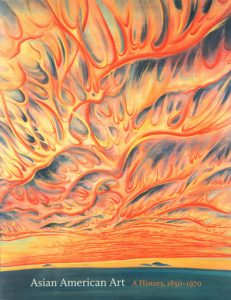

America: Painting a Nation at the Art Gallery of NSW presents an image of America that you might not have expected. The survey of painted works is small – the collection includes around 90 pieces spread across only a few rooms, but it captures some of the key milestones and sentiments from across the nation’s history, from colonisation to now.

Continue...

America: Painting a Nation at the Art Gallery of NSW presents an image of America that you might not have expected. The survey of painted works is small – the collection includes around 90 pieces spread across only a few rooms, but it captures some of the key milestones and sentiments from across the nation’s history, from colonisation to now.

Continue...  Yun Gee's art career was closely related to his personal life experiences. His social and political involvement, together with his relationships from the places he lived, made a great impact on the painterly style of his work.

Yun Gee's art career was closely related to his personal life experiences. His social and political involvement, together with his relationships from the places he lived, made a great impact on the painterly style of his work.

Rather than follow a traditional Eastern aesthetic, Gee gravitated toward European modernism, especially Orphism – a derivation of Cubism coined by the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

Rather than follow a traditional Eastern aesthetic, Gee gravitated toward European modernism, especially Orphism – a derivation of Cubism coined by the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

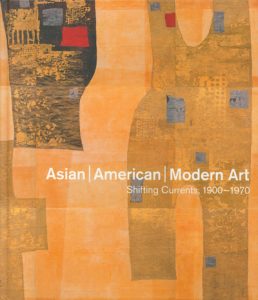

Works in the exhibition by early- twentieth-century artist Yun Gee exemplify a patter of shifting attention among artistic currents in Asia, America, and Europe.

Works in the exhibition by early- twentieth-century artist Yun Gee exemplify a patter of shifting attention among artistic currents in Asia, America, and Europe.

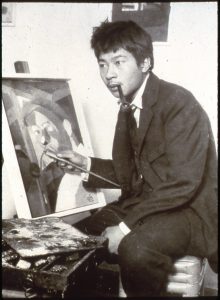

[Yun Gee's] early artistic career showed promise, and he was accepted by the artistic circles in San Francisco, and later in Paris and New York.

[Yun Gee's] early artistic career showed promise, and he was accepted by the artistic circles in San Francisco, and later in Paris and New York.

In the effort to determine possible features of an Asian American relationship to modernism (ways in which the various shared experiences of these communities we have decided to treat as one in this book may be reflected in the art), the life and work of Chinese American Yun Gee offers an excellent starting point.

In the effort to determine possible features of an Asian American relationship to modernism (ways in which the various shared experiences of these communities we have decided to treat as one in this book may be reflected in the art), the life and work of Chinese American Yun Gee offers an excellent starting point.

Today Gee is the best-known Chinese American artist active in the first half of the twentieth century, appreciated especially for the strikingly modernist paintings he made in San Francisco in the 1920s. Continued...

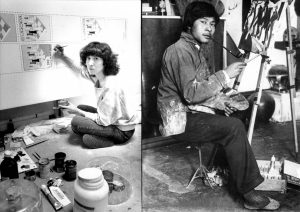

Today Gee is the best-known Chinese American artist active in the first half of the twentieth century, appreciated especially for the strikingly modernist paintings he made in San Francisco in the 1920s. Continued... Biracial artists like Maya Lin and Li-lan and transnational artists like Yun Gee may be burdened by the effects of racism and bigotry, but the perceptions they gain from their location in the "third space" may provide them with insights that strengthen their resolve and enrich their art practice.

Biracial artists like Maya Lin and Li-lan and transnational artists like Yun Gee may be burdened by the effects of racism and bigotry, but the perceptions they gain from their location in the "third space" may provide them with insights that strengthen their resolve and enrich their art practice.

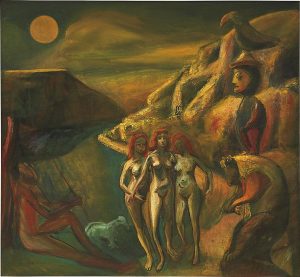

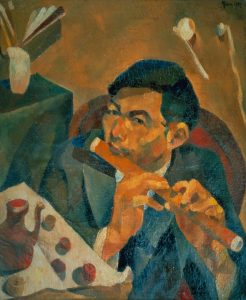

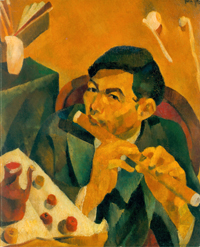

A remarkable self-portrait, an oil painting called The Flute Player by Yun Gee, is an even more self-conscious expression of eclecticism and daring.

A remarkable self-portrait, an oil painting called The Flute Player by Yun Gee, is an even more self-conscious expression of eclecticism and daring.

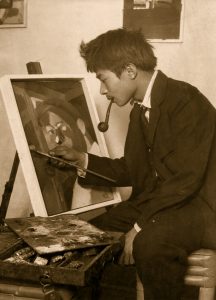

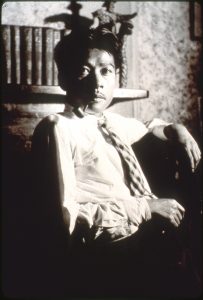

Who was Yun Gee? A painter, musician, dancer, teacher, theorist, inventor, and more. A poor immigrant with a wealth of creative ideas. A solitary philosopher who actively promoted the arts. A dreamer whose personal vision and ambitions were thwarted by the political and social realities of his day.

Who was Yun Gee? A painter, musician, dancer, teacher, theorist, inventor, and more. A poor immigrant with a wealth of creative ideas. A solitary philosopher who actively promoted the arts. A dreamer whose personal vision and ambitions were thwarted by the political and social realities of his day.

One of Oldfield’s students was the talented young Chinese American Yun Gee, whose still lifes of 1926 and 1927 reflect the importance of color and rhythmic flow of forms.

One of Oldfield’s students was the talented young Chinese American Yun Gee, whose still lifes of 1926 and 1927 reflect the importance of color and rhythmic flow of forms.

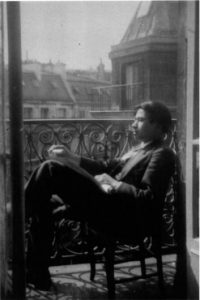

If in his poetry Gee wrote about the pleasures and pains of a simple material life, grand ideas that could be extracted from banal events, or the meanings that could possibly be construed during moments of hunger and poverty, he had ample experience with the subjects.

If in his poetry Gee wrote about the pleasures and pains of a simple material life, grand ideas that could be extracted from banal events, or the meanings that could possibly be construed during moments of hunger and poverty, he had ample experience with the subjects.

Perhaps I was ten years old, or even younger. I remember the quiet of his dimly lit studio. My father would sit at the dining room table, newspapers covering the worn surface, brush in hand, focusing all his attention on the paper in front of him. Only the shrill cries of his birds interrupted the silence. . .

Perhaps I was ten years old, or even younger. I remember the quiet of his dimly lit studio. My father would sit at the dining room table, newspapers covering the worn surface, brush in hand, focusing all his attention on the paper in front of him. Only the shrill cries of his birds interrupted the silence. . .

Among Asian-American modernists of note whose oeuvres visibly melded styles, techniques and sensibilities from the East and West was Yun Gee, who left southern China in 1921 to join his immigrant father, who had already settled in San Francisco. There, a lively art scene exposed Yun Gee to California Impressionism and other European-derived modernist styles.

Among Asian-American modernists of note whose oeuvres visibly melded styles, techniques and sensibilities from the East and West was Yun Gee, who left southern China in 1921 to join his immigrant father, who had already settled in San Francisco. There, a lively art scene exposed Yun Gee to California Impressionism and other European-derived modernist styles.

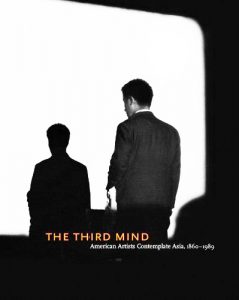

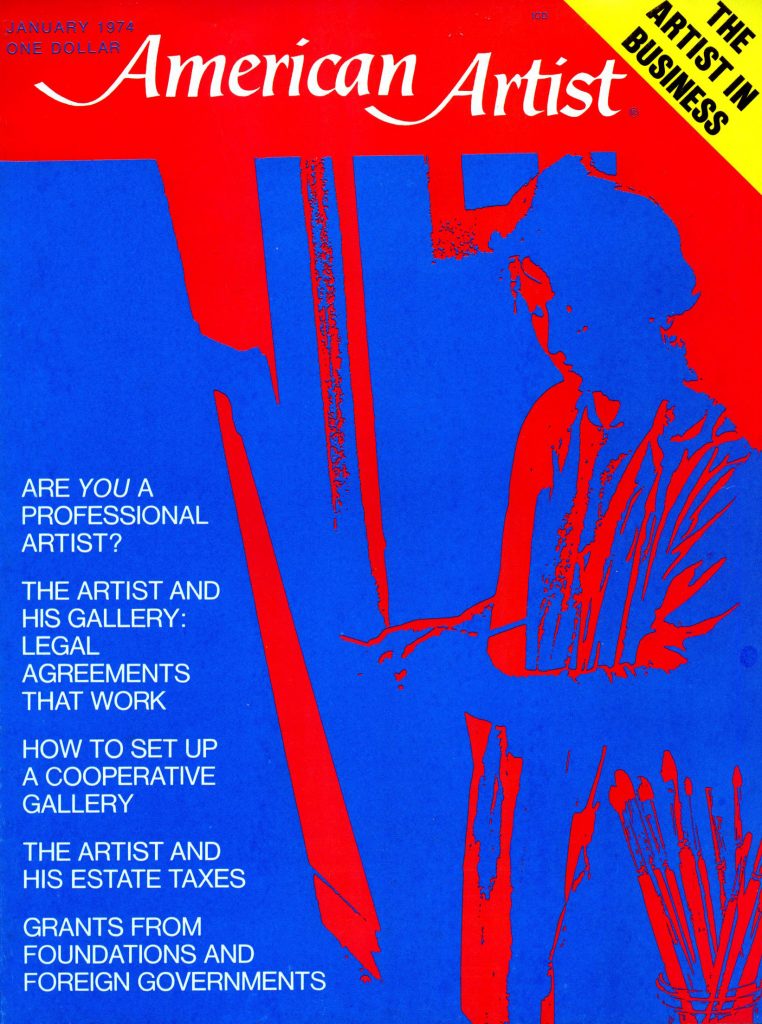

Many decades before a current generation of young Chinese artists living in the United States achieved international recognition, Yun Gee (1906 – 1963), a restlessly inventive painter, sculptor, poet, and performer born in Guangdong province, held one-man shows in San Francisco, exhibited in Paris galleries, and gave classes in “New Cubism” in his Greenwich Village apartment – all before reaching the age of thirty.

Many decades before a current generation of young Chinese artists living in the United States achieved international recognition, Yun Gee (1906 – 1963), a restlessly inventive painter, sculptor, poet, and performer born in Guangdong province, held one-man shows in San Francisco, exhibited in Paris galleries, and gave classes in “New Cubism” in his Greenwich Village apartment – all before reaching the age of thirty.

We know very few details about a remarkable artists’ collective in 1920s Chinatown, the ambitiously named Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club. It has left little trace, though some important facts remain. The club was formed during an intensely anti-Chinese moment in San Francisco – just two years after the passage of the 1924 Immigration Act, the harshest legislation yet passed to exclude the Chinese from the United States.

We know very few details about a remarkable artists’ collective in 1920s Chinatown, the ambitiously named Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club. It has left little trace, though some important facts remain. The club was formed during an intensely anti-Chinese moment in San Francisco – just two years after the passage of the 1924 Immigration Act, the harshest legislation yet passed to exclude the Chinese from the United States.

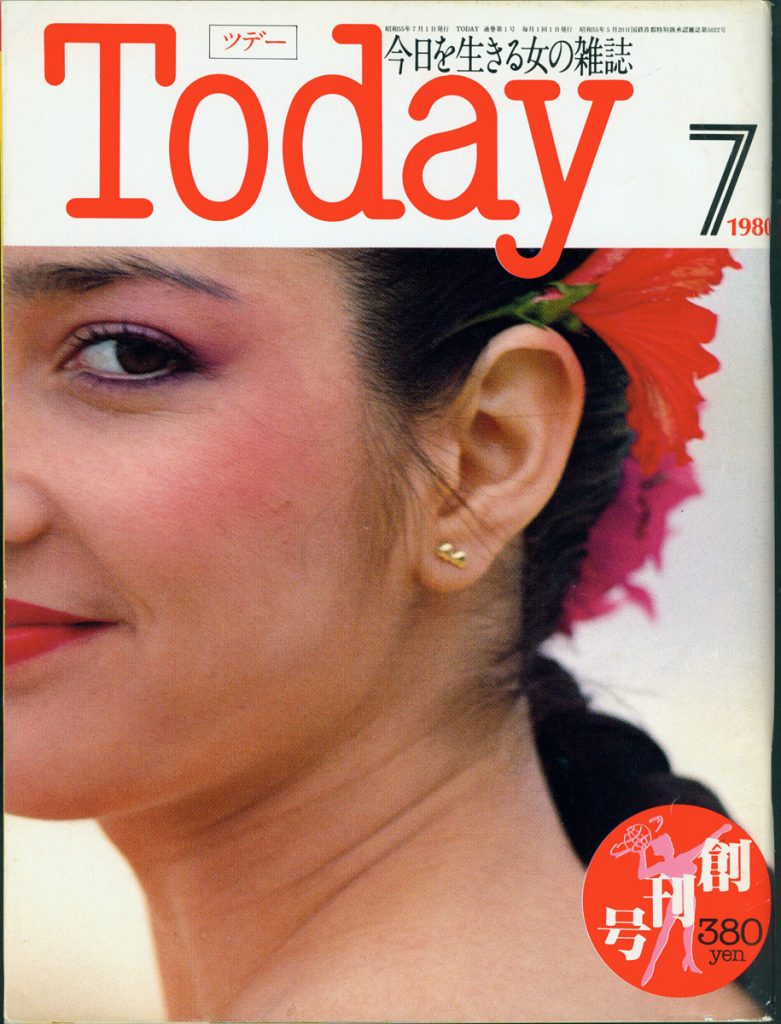

Ten years ago, when American ceramic artist Mrs. Camille Bilops was invited to give lectures on American Drama in Kaohsiung Normal College, she showed several slides of Yun Gee's paintings during a speech session introducing American Artists in New York City...

Ten years ago, when American ceramic artist Mrs. Camille Bilops was invited to give lectures on American Drama in Kaohsiung Normal College, she showed several slides of Yun Gee's paintings during a speech session introducing American Artists in New York City...  As a small child, I saw stacks of paintings in his studio, piled high, turned in towards the walls. I often wished those paintings could move outside to take their place in a bigger world. Just as it would move my father, it moves me that his work is now being celebrated by his countrymen.

As a small child, I saw stacks of paintings in his studio, piled high, turned in towards the walls. I often wished those paintings could move outside to take their place in a bigger world. Just as it would move my father, it moves me that his work is now being celebrated by his countrymen.

Yun Gee belongs to the forefront of early twentieth century avant-garde American art. This exhibition highlights his work of the 1920s and early 1930s, the period when he definitely found his own way by pushing the modernist legacy of the School of Paris forward into deeply personal and strikingly poetical directions.

Yun Gee belongs to the forefront of early twentieth century avant-garde American art. This exhibition highlights his work of the 1920s and early 1930s, the period when he definitely found his own way by pushing the modernist legacy of the School of Paris forward into deeply personal and strikingly poetical directions.

It was the early forties, and the world was at war. A young Chinese man sat in a Greenwich Village studio, philosophizing and dreaming with friends. Canaries, nightingales, and skylarks sang in birdcages. A candle flickered next to a human skull. . .

It was the early forties, and the world was at war. A young Chinese man sat in a Greenwich Village studio, philosophizing and dreaming with friends. Canaries, nightingales, and skylarks sang in birdcages. A candle flickered next to a human skull. . .

Seated before us is the painter. He is plucking the strings of a “yungkum,” (Chinese mandolin), with a bamboo shoot. Beside him are his only friends. . .

Seated before us is the painter. He is plucking the strings of a “yungkum,” (Chinese mandolin), with a bamboo shoot. Beside him are his only friends. . .