Over the course of this century, China has experienced protracted internal unrest, civil war, and the encroachment of foreign powers. As a race traditionally strongly attached to the land, the Chinese thus reluctantly began the largest outward population movement in their history. This tide of emigration, begun in the late 19th century through the turn of the century, has never abated through our present era at the end of the century.

Given this historical reality, and with the deepening of Post-Modern discourse, approaching the lives and works, psychological and artistic conditions and artistic significance of the first generation of Chinese artists in their adopted lands from the perspective of discourse on Chinese diaspora, exile, and emigration provides an appropriate and vital key to enhanced understanding of various aspects of their lives and careers.

Yun Gee (1906-63) was born during the waning days of the last Chinese empire. The revolution was ready to explode, and young intellectuals were ready to take up the fight to bring about a democratic system of government, freedom, equality, and brotherly love. The hotbed of revolution was none other than Yun Gee’s birthplace, Guangdong Province.

Yun Gee

Following the success of the revolution, China was unable to find lasting peace or to develop into a new democratic society. A succession of unrest–from internal conflicts, to domestic disorder, and civil war–and the progressive takeover of Chinese territory by the Western powers, threw Chinese politics and society into a long, murky period of darkness. “Saving the nation” thus became the grand dream of the period’s patriotic youths; across the political stage and intellectual circles leading elites agreed that China could not transform herself alone. The power of tradition dissipated, and mere reflection or returning to tradition could never save the nation; rather, salvation could only be achieved by learning from the West, especially about science and democracy.

Even in the art world, the young painter Xu Beihong had fallen under the spell of reformer Kang Youwei–another Cantonese–who urged the artist to pursue study in France. By studying the techniques of classical Western realistic painting, they sought to give traditional Chinese painting, which they saw as declining, a much-needed shot in the arm. Another source of Western input was actually Japan, as prior to the overthrow of the Qing dynasty such artists as Cantonese Gao Jianfu (1879-1951), a returned student from Japan, deliberately incorporated Western perspective and Cubist techniques into his work. Upon his return to China, Gao also threw himself into the revolution. The involvement of art and artists in the “national salvation movement” is thus a major issue in 20th century Chinese art.

In 1921, Yun Gee, just 15 years old, traveled to San Francisco to join his father. The China Gee departed was an odd mixture of chaos and disorder tinged with a faint light of hope. The previous year (1920), Sun Yatsen, the father of New China, had established military governments in Shanghai and Guangdong, and had assumed the title of provisional president. On July 1 of the same year, the Chinese Communist Party was founded in Shanghai.

Yun Gee was united with his father in America, yet the United States’ Asian Exclusion Act prohibited legal immigration by Chinese women, forever preventing a reunion between mother and son. Yun Gee’s mother soon became the object of constant longing. For Yun Gee, facing the daily scorn and official prohibitions of the Chinese Exclusion Act in a nearly exclusively Caucasian society, the distant land across the Pacific and the mother trapped there, became a spiritual crutch and a recurring theme in his work.

Yun Gee – San Francisco

Yun Gee – San Francisco

In America, Yun Gee received orthodox arts training in an art institute, where he earnestly studied Western modern art. Yet the injustices of the society to which he had emigrated seemed to only strengthen his conviction that the Chinese revolution must succeed and that China must become strong as a nation. Between October 1924 and June 1927, Gee carried out his studies at the California School of Fine Arts.

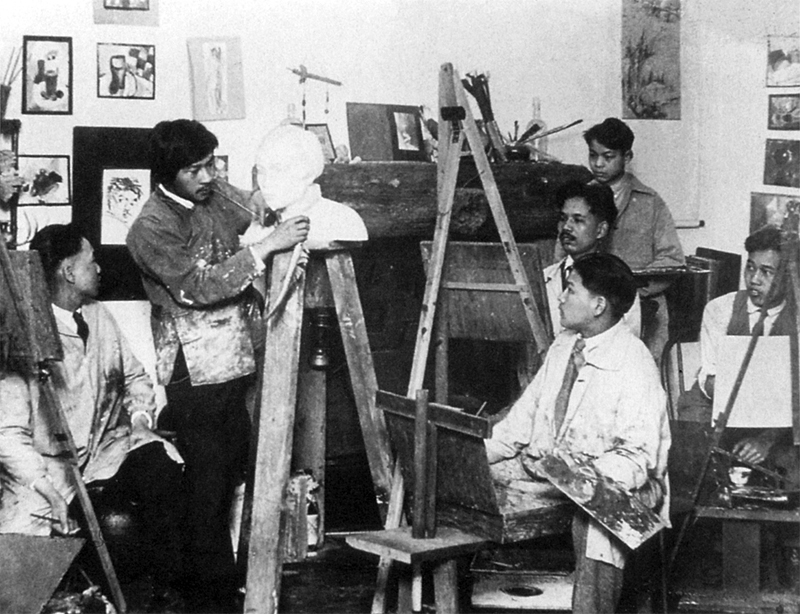

Outside his formal studies of Western art, Gee continued to act on his commitment to China, establishing the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club in San Francisco to teach young Chinese modern art theory and painting. The club’s name is especially revealing, as it indicates the intense hopes and expectations Gee placed on the Chinese revolution, on the salvation of the nation and on national salvation through art. It is worth noting that Sun Yatsen, the revolutionary who dedicated himself to the overthrow of the Qing dynasty and the establishment of the Chinese republic, died in 1925. Among his last words was the admonition: “The revolution has yet to succeed. Our comrades must keep up the struggle.”

Yun Gee – Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club, San Francisco

Yun Gee’s attachment to China can be seen in the way he signed his Chinese name on paintings between 1926 and 1928, and his practice of dating the paintings according to the Chinese Republican system. Such deliberate reference to identity is clearly a natural and complex response to the clash with practice of the alien Western modern art tradition upon arrival in America.

Yun Gee’s early San Francisco period also marked a time of study and experimentation. Drawing on training in the style of Synchronism style, Gee analyzed and composed the human forms and scenes in his paintings with bright abstraction and contrasting colors. The effect is that of strong opposition: sober and distant, yet lyrical, mechanical yet sentimental–or even melancholy. Moreover, this simultaneously abstract and figurative style sometimes exhibited a strong taste of Expressionism. The emotional contrasts and alternation between hot and cold in his works are quite fitting for San Francisco, a city which while bathed in ample sunshine is constantly buffeted by the chilling breeze of the nearby bay. A new arrival in San Francisco, Yun Gee was in the sentimental years of youth, and separation from his beloved mother in the strange land of the West forced him to mature before his time. Apart from his acute sensitivity to cultural differences, the vastly different environment and customs of his new home were distilled through his heightened sense of separation.

Yun Gee left San Francisco in July 1927 to establish a career for himself in Paris. Unlike San Francisco, a city still very much in the midst of growth and development, venerable Paris was an established cultural capital. The magic of Paris was a great lift to Yun Gee’s spirits, inspiring him to say, “I forgot that I was in a strange land and that my home in Canton was thousands of miles away.”

This statement points to the various differences between Paris and San Francisco. In addition to viewing the priceless treasures housed at the Louvre Museum, Gee became acquainted with many figures active in the Paris art scene, among them critics and agents. With the help of appreciative agents, Yun Gee held several solo exhibitions at various Paris galleries and gained entry into the 1928 Independent Salon Exhibition. For the artist, just barely into his 20s, the future must have seemed pregnant with limitless possibility.

Paule de Reuss – Paris

While in Paris, Yun Gee “settled down to achieve [kinship between East and West].” It was also at this time that his acquaintance with French poet Paule de Reuss blossomed into love, and the two were married in February 1930. Perhaps affected by the prevalence of Surrealism, Gee’s works began to take on a dreamy quality in Paris, a characteristic perhaps directly connected with the artist’s growing interest in Freud’s interpretation of dreams and theories on psychoanalysis.

At this point, the Syncronism evinced by the strongly contrasting color blocks and fields during his earlier San Francisco period began to soften. In Paris, he began to employ gradation of neighboring tones and repetition of parallel strokes to create tangible figures and objects, as well as Cubist scenes with a highly accented sense of perspective–in effect strengthening the figuration in his work. Further, yellows strongly reminiscent of Van Gogh also began to appear heavily in Yun Gee’s paintings.

Between 1928-29, an increasing element of existential consciousness and dialectics on life and death began to appear in Yun Gee’s work. Prominent examples are Life and Death and Chinese Man in Hat (notable for the Chinese inscription) from 1928 and The Red Chair and Butterflies: Dream of Chuang-Tze from 1929. Interestingly, Gee’s color palette shifted towards darker, heavier tones during these two years, a far cry from the characteristic brightness of the preceding San Francisco period.

Dreamscapes, memories, self-portraits (or sculptures), and subject matter from traditional Chinese culture became important and prominent areas of thematic concern during his Paris period. The depiction of himself wandering the streets of a foreign land in a dream hints at Freud’s theories on the interpretation of dreams, and the attempt to engage in self-analysis or psychoanalysis through painting. Alternately, Yun Gee employed an abstract approach to the representation of memories or visions of traditional Chinese landscape paintings. He also drew from Chinese allegories, subject matter from Chinese opera, and from the formal language of traditional Chinese painting. In such works as Imperial Concubine Exiting the Bath (1929), he employed these elements much in the style with which such pre-Renaissance masters as Giotto depicted parables from Christianity. On the other hand, he took a decidedly Western Modernist approach to subjects and stories integral to Chinese culture, including the masters Confucius and Chuang-Tze. Perhaps these examples represent what the artist meant by developing the ‘kinship between East and West.’

While France lacked a Chinese Exclusion Act, and Yun Gee’s career seemed destined for great things in Paris, possessed with the keen sense of a foreigner in a foreign land, Yun Gee nonetheless detected the strong cultural superiority of the French and their disdain for Americans and Chinese. No doubt Yun Gee’s experience with prejudice in American society heightened his sensitivity toward similar contempt in French society. In France, a nation with no official exclusionary policies or laws, a cultural smugness pervaded Parisian society, clearly bruising his sense of self and cultural pride. Perhaps in an effort to compensate for the psychological frustration of this experience, while in Paris he adopted a high moral line, criticizing Paris as a “restless city” of decadent moral character. In unequivocal terms, he exclaimed, “Civilization, and withal savagery, can I tolerate this?”

Yun Gee – Paris

Ever mindful of this tenor in Parisian society, Yun Gee selected the great representatives of Chinese culture as subject matter, perhaps as a means to confront the French and test their learning and cultural depth. Deliberately invoking allegories of the great Chinese thinkers may have been his attempt to moralize among the French. Granted, a longing for Chinese culture probably also played a significant part in the adoption of this attitude.

The worldwide economic panic in the wake of the New York Stock Exchange crash of October 1929 cast a cloud over Yun Gee’s future in Paris. Feeling the pinch, the newly married Gee returned to America alone, where he settled in New York with an eye for cultivating the second stage of his artistic career. Returning to the U.S., he remained hopeful that he could help bring about “sincere cooperation between East and West” among young Americans of Chinese and Caucasian backgrounds. From these accounts, an underlying concern for the prejudice and rejection by American society towards him as a Chinese is clearly evident.

Anguish and nightmares over prejudice continued to shadow Yun Gee. New York in the throes of the Great Depression once again reminded the young artist of the pervasive racial prejudice in society, prompting him to complain of the “apathetic coldness.”

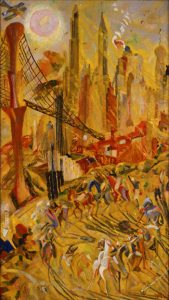

Wheels: Industrial New York

Wheels: Industrial New York

1932

oil on canvas

This somber mood stands in stark contrast to that evoked by Wheels: Industrial New York, a large work exhibited in 1932 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. With the sun high in the sky, readily identifiable New York landmarks including skyscrapers and the Brooklyn Bridge dominate the background, while in the foreground industrialists playing polo, representing the grand wheel powering New York’s industry, form a circle. Rather than describing this work as highly reminiscent of political propaganda, it would be more accurate to note the subtle satire of capitalist society underlying the tone. An additional work depicting New York industry shows the elongated figures of two sleepy-eyed workers, welding in New York City under the blanket of dark night, a crescent moon high above. Skyscrapers and a bridge also occupy the background of this painting; what distinguishes this work from the previous work is that the welders occupy a far greater proportion of the painting than the polo-playing capitalists do. The contrast presented by these two works goes far in illuminating Yun Gee’s observations and perspectives on American society.

Upon returning to America, while determined to further his artistic career, Yun Gee maintained close ties with the Chinese community. His active participation in cultural and artistic activities in the Chinese community sometimes even had him shuttling between New York and San Francisco. Moreover, at this time he observed developments in China with keener interest than ever. In response to Japanese encroachment of China in the 1930s, Yun Gee launched a political mobilization campaign, calling on Western society to take notice. His work also took on a political tone as he produced a series of satirical political cartoons published in Chinese-language newspapers to alert the world to the atrocities occurring in his native land.

In 1935, Yun Gee joined up with the WPA (Work Promotion Association), established by the US government to assist cultural workers and artists get through the dismal economic times of the Great Depression. His participation in the program seems to demonstrate the difficulty Gee would have realizing the ambitions he held for his artistic career in New York in the early 1930s. Previously, lacking financial support and sensing the difficulty Yun Gee was having in getting his career off the ground in New York, his French wife had filed for divorce in 1932. This was surely a major blow to the young artist. Nevertheless, his involvement in the WPA soon led to an acquaintance with, Helen Wimmer, who later became his second wife.

Having joined up with the WPA, Yun Gee had apparently become aware of the limitations on his development in New York art circles. Throughout this time, the weight of white society’s prejudice against Chinese remained heavy on his mind. Perhaps it was this mental torment which impelled the artist to return to Paris once again in 1936 in hopes of recapturing the magic moments of his previous stay in Paris. While in Paris, Gee maintained frequent and close contact with Helen.

Based on records from Paris exhibitions in the late 1930s, Yun Gee was right back in his element in Paris, not only taking part in joint or group exhibitions side by side with renowned artists, but also gaining an opportunity to exhibit 37 works in a one-man show. But alas, all good things must come to an end, and with the outbreak of World War Two in 1939, Yun Gee once again headed back to New York.

Two years before the outbreak of war in the European Theater, China had formally declared war against Japan on July 7, 1937 in response to the expansion of Japanese militarism into China. In distant Paris, Yun Gee produced paintings and sketches protesting the atrocities of the Japanese military in China in order to arouse sympathy and action. Upon his quiet return to New York, he became even more consumed by anti-Japanese salvation activities, selling works of art to raise funds for the Chinese war effort. In order to survive, he once again signed up with the WPA in 1941, teaching landscape painting at the City Museum of New York. Between 1940 and 1942, he continued to hold solo shows to raise funds for the Chinese cause.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, triggering the US declaration of war and a full-scale effort on the Pacific front. In January 1942, after a six-year courtship, Yun Gee and Helen were married. Li-lan, their only daughter, was born in late February the following year. During the latter half of the war (1942-44), Yun Gee was employed at a defense industry-related company. According to Helen Gee’s memoirs, throughout this period Yun Gee worked a full six days per week, returning home from work at the end of each day to paint through the night. Eventually, having pushed himself too hard, he would develop a number of chronic maladies.

To date, the dearth of detailed information (at least in Taiwan) on Yun Gee’s return to Paris in the late 1930s, and on his life and artistic endeavors after returning to New York in the 1940s, prevents a systematic account of his life and works or a comprehensive analysis of the second half of his life. Still, it can be inferred from what we now know that Helen Gee separated from Yun Gee in 1945 and divorced him in 1948. It is also known that Yun Gee met Ms. Velma Aydelott in 1950, with whom he lived until his death in 1963. Following the artist’s death, Ms. Aydelott turned over most of Yun Gee’s later works and materials to his only daughter, Li-lan.

Today, nearly no reliable information is available on Yun Gee’s life and work between the separation from Helen and his death other than that which can be recollected by Li-lan on her experiences together with her father. These facts illustrate Li-lan’s indispensable role in the further investigation of the latter half of Yun Gee’s life.

This exhibition of Yun Gee’s works from the collection of Li-lan at the Lin & Keng Gallery includes a rare, highly figurative work dating from 1951. This particular work shows that while Yun Gee had adopted a realistic figurative style by the 1950s, he had nonetheless continued to paint. Information provided by Li-lan also indicates that Yun Gee taught painting in his home studio during his later years. He may also have engaged in the buying and selling of art works, and apparently dreamed up a number of innovations and inventions, such as variations on chess and checkers enabling two to four players to play at the same time.

Additional analysis or follow-up investigation on the characteristics and changes in Yun Gee’s style will have to await further scholarship and discoveries.

Chia Chi Jason Wang lives and works in Taiwan as a curator and art critic. He graduated respectively from the English Department of Fujen Catholic University (B.A., 1984), the Institute of Fine Arts of Chinese Culture University (M.A. in Art History, 1986), and the Group in Asian Studies of the University of California at Berkeley (M.A., 1991). He was the curator of the Taiwan Biennial 2008, the Taiwan Pavilion at the 51st International Art Exhibition of the Biennale of Venice 2005, and the 9th International Architecture Exhibition of the Biennale of Venice 2004. He also worked as co-curator of the 2002 Taipei Biennial Great Theatre of the World. His other positions included Curator of Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei (2001), and Executive Director of the Dimension Endowment of Art (2001-1002).

•BACK•