Yun Gee belongs to the forefront of early twentieth century avant-garde American art. This exhibition highlights his work of the 1920s and early 1930s, the period when he definitely found his own way by pushing the modernist legacy of the School of Paris forward into deeply personal and strikingly poetical directions. In this selection of landscapes and urban scenes, portraits, still lifes and interiors, Yun Gee reveals the essence of reality in all it’s dynamically sensual and intimately emotive splendor. The experience these examples offer is of a way of seeing that immediately triggers feeling. A trademark of genuine, first-rate expression, the strong impact of these pictures is due to the artist’s keen ability to imbue color with extra-perceptual sensations.

At the source of the compelling vision of Yun Gee is his intense experience of life. Born near Canton, China in 1906, he left his native village at the age of 15 to join his father in San Francisco. Although he had studied traditional Chinese watercolor painting as a child, once settled in San Francisco, he decided to develop as an artist along a definitive Western route. In 1924 he enrolled at the California School of Fine Arts, now the San Francisco Art Institute. During the two years he attended classes there, he quickly went through the typical academic program only to concentrate on the most advanced styles available to him. Yun Gee, through his teachers, the painters Gottardo Piazzoni and Otis Oldfield, cast his lot with the so-called “ultra-modernist” faction that sprang up in the growing West Coast art center of San Francisco in the mid-1920s. From Piazzoni, a popular landscapist of Impressionist persuasion, but mainly from Oldfield, a native Californian who had lived in Paris and experienced its impact first-hand, he learned about the French modern school from Post-Impressionisms through Cubism and Futurism, and was exposed to Synchronism – the American spin-off of Robert Delaunay’s Orphic Cubism – launched in Paris in 1913 by the Americans Morgan Rusell and Stanton MacDonald-Wright.

In 1926, Yun Gee’s fist one-person show at the cooperative space he helped found with Oldfield, and propitiously called The Modern Gallery, attracted the attention of the Prince and Princess Achille Murat, active patrons of the Paris art scene who were passing through San Francisco at the time. They bought several of his paintings and, with their encouragement and the promise of future support, Yun Gee left San Francisco in July 1927 to begin the second phase of his career in Paris.

Street Scene

Street Scene

1926

oil on paper board

11 x 15 5/8 inches

Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art

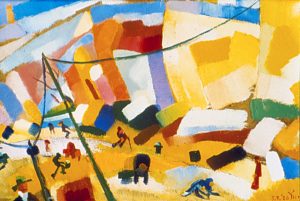

In the paintings executed in San Francisco in 1926 and 1927, Yun Gee displayed a perceptive understanding of Cézanne, Fauvism, Cubism and Synchromism. Concentrating on each one’s distinctive use of color, he would combine more than one influence often in a single picture. In Landscape With Two Trees (1926), the shifting grid of colored planes brings to mind Cézanne and the high-keyed yellows and reds recall Fauvism. In Houses on a Hill (1926), the fanning composition and shining transparent and fractured surfaces recall Picasso’s early Cubist landscapes of 1909, and Fernand Léger’s city-scapes of 1910. Delaunay’s principle of simultaneous contrasts at the source of Synchromism is freely applied in the luminous juxtapositions of primaries and their component complements in San Francisco Street Scene, Street Scene, and Girl on Bridge (collection: Whitney Museum of American Art), all dated 1926.

Girl on Bridge

Girl on Bridge

1926

oil on paper

10 1/2 x 16 inches

This principle is applied in “San Francisco Street Scene,” for example, to communicate the inherent dynamism of modern urban life. Here, the subtle variations in the direction of the brushwork help create the vivid illusion of movement in depth among the yellow, blue and green wedges. Still, the caricaturish figure of the old man with a hat and cane jauntily strolling in the foreground adds a humorous touch, indicating the artist’s subtle gift of observation. In Girl on Bridge, the startling fresh colors are flush with mystery. They define a fanciful and suggestively narrative space dominated by a golden arc of a bridge across which a girl seems to run and from which a car appears to be falling. Yun Gee’s talent for using the superficially objective device of rhymed colored planes, derived from Cubism and Synchromism, and turning it towards subjective ends is tellingly illustrated in the still life Skull (1926) (collection: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden) and the selected portraits and figures in landscapes.

Skull

Skull

1926

oil on paper board

11 1/4 x 15 1/2 inches

In Skull, the sharp tonal dissonances sound a plaintive note in tune with the subject and echoed by the uneven staccato rhythms of the composition. While in Man Holding Baby (1926), the harmonious resolution of contrasts and smooth planar rhythms reinforce the state of love and security signified by the gestures and expressions. In Seated Man Wearing a Hat (1926), the structure of interlocking colored planes gives a definite sense of body weight and posture. In Chinese Musicians (collection: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden) (c. 1927), this same structure is applied uniformly to figures and the landscape in a swirling network of curvilinear shapes accented by intervals of repeated colors.

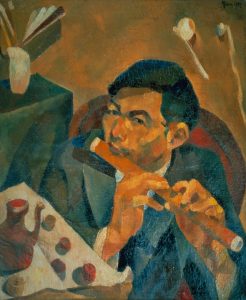

In the Portrait of Gottardo Piazzoni and Man With Pipe, actually a portrait of Otis Oldfield, both c. 1927 works, Yun Gee has returned to the Post-Impressionist roots of the radical reconstruction of reality implicit in all the San Francisco period paintings. In both of these pictures, the restrained but nevertheless riveting application of the Fauves-like touches of green not only accentuate the planes of the faces but introduce an engaging note of timelessness to these otherwise causal and momentary poses. These portraits also anticipate the heightened expressive dimensions that emerged in his painting executed in Paris.

The Red Chair

The Red Chair

1928

oil on canvas

28 7/8 x 23 5/8 inches

In Paris, Yun Gee, through the contacts of the Prince and Princess Murat, was introduced to the sophisticated art and literary circles. Among the luminaries he met were Gertrude Stein and such varied supporters of his work as the painter André Lhote and writers Paul Guillaume and Pierre Mille. From 1927 to 1929, he had four one-person shows at leading Parisian galleries, including the prestigious Galerie Bernheim-Jeune. In this stimulating environment, Yun Gee consolidated his means. Where is My Mother? (1926-27) and Pantheon and Workmen (1927), two paintings finished early during his stay in Paris, look both back and ahead. Their sweeping compositions, peculiar raked space and hues recall Chinese Musicians and House on a Hill, respectively. But in the Parisian pictures, color articulates a more easily recognizable but no less conceptualized imagery. In The Red Chair and particularly in The Flute Player, both 1928 examples, Yun Gee reveals a fully developed temperament in the French modern sense of representing reality according to a unique personal vision. In The Flute Player, a self-portrait, the artist renders himself playing the musical instrument while seated in an interior. The picture’s distinctive bird’s-eye view and radically cropped setting intensify a spirit of meditative engagement.

The Flute Player

The Flute Player

1928

oil on canvas

23 x 19 inches

In 1930, the impact of the world-wide Depression hit Yun Gee hard. Finding it impossible to support himself and his wife in Paris (he had recently married Paule de Reuss, a poet from an aristocratic family which had disowned her for becoming his wife), he moved alone to New York where he hoped to make enough money to allow his wife to join him. She never did and practicalities necessitated that they divorce so that de Reuss could regain her family’s financial support.

Yun Gee remained in New York from 1930 to 1936. After his return, he had three one-person shows, including one at the Balzac Galleries, a respected mid-town showcase, and was invited to participate in two major group surveys. They were “Paintings, Sculptures, Drawings by American and Foreign Artists,” organized by Marie Sterner for the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 1931 that was an educational blockbuster of its day, and the controversial “Murals by American Painters and Photographers,” held by the new Museum of Modern Art in 1932. As conceived by Lincoln Kirstein, the MOMA mural show aimed to encourage the emergence of an indigenous American mural style by giving a select group of artists the opportunity to design a project that could be later commissioned. Yun Gee was in fine company here along with the likes of Stuart Davis, Georgia O’Keefe, Reginald Marsh, Ben Shahn and Philip Evergood. Each artist was asked to execute painted studies for a “horizontal composition in three parts” and a “large panel to measure seven feet by four feet wide.” The subject, according to Kirstein’s instructions, was to be “some aspect of the Post-War World.”

Merry-Go-Round | Sun Bathers | Modern Apartment

Merry-Go-Round | Sun Bathers | Modern Apartment

1932

oil on canvas

Yun Gee’s entries are included here in the exhibition. For his subject, he chose to represent the energy and activity typical of New York. The smaller paintings consist of Merry-Go-Round, Sun Bathers and Modern Apartment. The artist’s interest in recording New York street scenes is evident in the 1930 example Houses in the Bronx, in which average buildings are transformed into fanciful castles. In Merry-Go-Round, the popular amusement park ride is turned into a symbol of endless revolution.

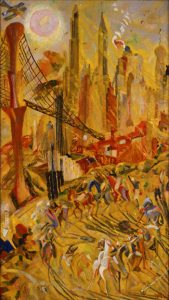

Wheels: Industrial New York

Wheels: Industrial New York

1932

oil on canvas

84 x 48 inches

In Wheels: Industrial New York, the large panel, the merry-go-round has become a ritualistic circle of polo players; although they too represent amusement, their game is elitist. In contrast to them, is the anonymous, collective force of the city towering behind. Wheels: Industrial New York is a symbolic city-scape in the modernist tradition of Delaunay’s views of Paris. Here, the Brooklyn Bridge and skyscrapers are the main reflectors of the spectral energy that appears to race through the composition. This parallels the Eiffel Tower as depicted in Dalaunay’s canvases. Red and yellow rays and shadows stressing the interplay of light’s effect emanate from the crystal sun shining in the upper left and bathe this scene in a spiritual resonance. Aside from the mechanistic polo players, only a few vulnerable figures populate the city. But their presence adds a poignant humanistic note.

In Sun Bathers and Modern Apartment, Yun Gee displays his talent for observation. The deft rendering of the woman’s dance-like poses and the slope of the rooftop animates the space, creating an inviting picture of languorous ease. In Modern Apartment, the luxury of the prevailing Art Deco interior is suggested with subtle finesse by the structuring of the composition through contrasting linear and color relationships.

In 1936, Yun Gee returned to Paris where he again showed at leading galleries often in the company of major French artists including Bonnard, Braque, Dufy and Soutine. The dealer Ambroise Vollard and writer Andre Salmon were among his most active supporters. No doubt what they valued is the power of his pictures to delight the eye and touch the emotions.

•BACK•