Chinese American Yun Gee (1906-1963) resided and traveled in three continents. Rooted in Asia and influenced by Modern Art in America and Europe, his art has earned him a reputation in the Western art world. Gee worked with a diverse range of media including oil painting, work on paper, as well as sculpture. He first arrived in San Francisco after emigrating from China to America. Later, he had two sojourns in Paris, France and finally settled in New York until the end of his life. In the places where he resided, his works were shown in exhibitions and collected in major museums. Gee was as much of a diligent writer and poet as he was a painter, often expressing his thoughts and opinions on Western Modern Art through poetry and essays. With music as another one of his passions, playing Chinese musical instruments and performing classical opera pieces were among the list of his many talents.

Yun Gee’s art career was closely related to his personal life experiences. His social and political involvement, together with his relationships from the places he lived, made a great impact on the painterly style of his work. Fortunately, this special exhibition features Gee’s art made in his three places of residence with oil paintings and works on paper ranging from his early period in 1926 through his later work in 1951.

San Francisco Period

San Francisco, the city on the West Coast, was not only the first stop for Chinese immigrants to enter into America in the early Twentieth Century, but also served as the essential and significant city where Gee was exposed to Western Modern Art for the first time. It really marked the starting point for Gee’s artistic journey.

Yun Gee, whose original given name was Gee Wing Yun, was born in Gee Village, Yanglu Town, Kaiping County, Guangdong Province of China on February 22, 1906. He was the second son of Gee Quong On and Wong See. In 1921, at the young age of fifteen, he left his hometown and joined his father, a naturalized American citizen, in San Francisco. According to archives, Gee lived on Spoffard Alley (now Spoffard Street), and later on Clay Street, both located in Chinatown.[1]

As an immigrant in America, Yun Gee certainly experienced the obstacles encountered by minorities in a foreign country. During this time period, known as the Exclusion Era that started in 1882, nearly all Chinese men and women were denied entry into the U.S. This was with the exception of special provisions for merchants, government officials, and students. In 1924, a more stringent Immigration Act was passed, barring all Chinese from entering America. Not until the 1952 McCarran -Walter Act was the exclusion lifted.[2] Under these unaccepting and unwelcoming circumstances, Yun Gee had conflicting emotions. On the one hand, he dearly missed his mother who was banned from coming to America and he still cared about the democratic developments in his homeland; yet he also strove to prove himself and wanted to continue his ambitions in this new world. All of these emotions were concealed in his colorful expressionistic artwork.

In 1924, Yun Gee entered the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco (now the San Francisco Art Institute) under the teaching of Otis Oldfield, who remained a life-long friend. At that time, Oldfield had come back from Paris where he had stayed for more than a decade, and introduced Synchromism to Gee. Synchromism is an art movement originally conceived in Paris, shortly before World War I. The movement is based on the theory that color provides the basis for both form and content. Synchromist paintings emphasize color rhythms as musical patterns, which are composed of abstract shapes to reveal pictorial subjects.

Otis Oldfield

Otis Oldfield

Under the influence of Oldfield and painter friends Gottardo Piazzano and Labaudt, Gee began to become familiar with Western modern paintings, particularly Cubism and individual expressionism. He worked on black and white sketches of sculptures of Michelangelo and Rodin, as well as figure studies, landscape, still-life, and portraits.[3] During this period, Gee experimented on his paintings with color palettes using different shades and tones. Forms were constructed using quasi-geometric shapes without sketching at the base. Variations of colors were employed to indicate three-dimensional forms and pictorial space.

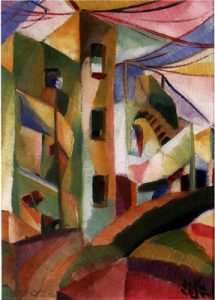

Telegraph Hill

Telegraph Hill

1926

oil on paper board

11 3/8 x 8 1/4 inches

In Telegraph Hill (1926), figurative composition and spatial layers are expressed by abstract shapes of colors. The hillside and buildings are formed by the integration of bright and dark shades. The composition with color contrast in Musician with the Erhu (1927) is far more dramatic. The dark background enables the musician subject figure’s bright tones to “show off” in the foreground, as if spotlights are directly on the musician on stage. The musician has a cubic face with sharp angles and high, arched eyebrows, looking askance towards the audience. Another noteworthy fact is that the musician is playing an Erhu, an instrument Gee knew well. The choice of this musical instrument implies the artist’s cultural background.

Yun Gee’s cultural roots can also be seen from the inscription on his work, which is similar to that of Chinese traditional ink paintings. The special calligraphic inscription on his works in the 1920s included the years dated in correspondence with the years of the Republic of China (with 1912 being referred to as “The first year of the Republic of China”). In addition, the Chinese characters of his signature resembled the writing style of the traditional engraved seal stamps. Although he resided in foreign places, Gee’s mind was always connected to his native country.[4] On the upper left side in Man Writing (1927), Gee used Chinese characters to record the completion year and place – the sixteenth year of the Republic of China, San Francisco, U.S.A. The juxtaposition of writing and picture is a unique feature found in traditional Chinese paintings. The narrow rectangular shape of Untitled (Abstract Figure) (1925-27) resembles a traditional Chinese vertical scroll. The central figure, composed of abstract shapes, seems to be playing a Pipa, a traditional Chinese musical instrument. Gee even wrote a poem on the upper left side of the painting, which describes how beautiful music inspires dancers, in their red and green luxurious costumes, to dance elegantly and intimately.

In addition, during the Exclusion Era, Gee was experiencing the burden of racism, which also made him deeply discouraged. However, under the local overseas Chinese patronage, Gee founded The Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club in San Francisco’s Chinatown, and began teaching modern art to Chinese immigrants. This was his own way of relating to China, and was also his way of responding to Dr. Sun Yat Sen’s idea of “art will save our country.”[5]

Prince and Princess Achille Murat

Prince and Princess Achille Murat

Gee and Oldfield were among the group of artists that established the Modern Gallery on Montgomery Street in 1926, which was a vanguard exhibition space, the first artist’s cooperative in the Bay Area in the early 1920s. In July 1927, with the support from his French friends, Prince and Princess Achille Murat, Gee departed for Paris and began the next stage of his art career, in Europe.

Paris Period

Gee had two sojourns in Paris, where his paintings received acceptance and recognition in the Paris art scene. During his first sojourn, he stayed for three years, from 1927 to 1930. He first made a stop in New York to arrange for a passport and bought a third-class ticket to Cherbourg, a seaport in northwestern France. After arriving in Paris, he settled in the Latin Quarter and later moved to Montmartre in 1928.[6] Due to the global economic recession that resulted from the Great Depression in America, his patronage was cut short. Gee was forced to leave Paris and chose to settle in New York instead. However, with limited opportunities for exhibitions to make a living in New York, he departed for Paris a second time. His second stay also lasted approximately three years, from 1936 to 1939. This time, he lived in the Fifth District and then moved to the Fourteenth District.[7] During this period, his friends in the art world supported him and he had winning exhibitions. However, as World War II broke out, the increasing racism against Chinese prevailed. Gee had to leave Paris again and resettled once more in New York.

In 1927, at the age of twenty-one, Gee went to Paris hoping to further develop in Western art, and striving to fuse his paintings of the East with that of the West. This was his fondest dream. In December of 1927, Gee had his first solo exhibition in Europe at the Galerie Carmine. Soon after, he exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants. In 1929, the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, a renowned gallery in Paris, held Gee’s solo exhibition, and his work was recognized. Gee was also acquainted with Raymond Duncan and Paul Guillaume, prominent figures in the art world.[8] During his second sojourn in Paris, Gee had two solo exhibitions at the Galerie à la Reine Margot, and his work was exhibited widely and received positive reviews, including a few written by Pierre Mille.[9]

My First Impression of Paris

My First Impression of Paris

1927-28

oil on canvas

29 x 24 inches

Upon his arrival in Paris, Gee continued to work on his Sychromist paintings in a quasi-Cubist style. In My First Impression of Paris (1927-28), distorted buildings are arranged to form a semi-circle that contains figures of different positions in a gathering square. The man in the foreground at the lower right hand side of the painting may be the artist himself pondering his thoughts. The subject in Pantheon and Workmen (1927) features The Pantheon, a prominent architectural structure in the West. The Pantheon is depicted from a low angle to display its grandness and divinity, while the relatively small-scale workmen with their heads hanging low are busy at work. This composition may imply his concerns with the condition of the working class in society. Untitled (Madrid Landscape with a White House) (1929) was painted after Gee had traveled to Spain in 1928 for six months. The picturesque country and hospitable people there impressed him.[10] The hues in this piece are darker compared to the variety of color employed in his early paintings. The forms that are composed of colors are well blended with each other gradually, without any sharp marginal lines or contrasting colors between them. The continuous mountain ranges and trees in the background are painted with a smooth gradation of colors.

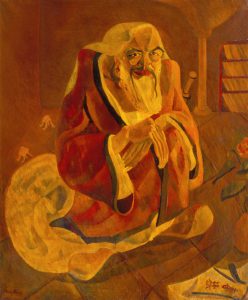

Confucius (Chinese Sage)1929

Confucius (Chinese Sage)1929

oil on canvas

48 3/8 x 40 3/8 inches

During his periods in Paris, Gee executed some of his paintings with Chinese motifs, including Confucius (1929), Empress Yang Kwei Fei at Her Bath (1929) and Butterflies: Dream of Chuang-Tze (1929), among other masterpieces. This seemed to be Gee’s attempt to embrace Western Modern Art while at the same time transcending into Chinese paintings. The integration of Eastern and Western cultures served as his motivation to explore Western Modern Art from the very beginning. He stated that the modern technique of painting “was most like the traditional creative expression of my native China in its freedom, its distortion of forms and its emphasis on atmosphere.”[11] During this period, one might find that there were less geometric forms in the pictorial composition, but with a more linear depiction. There also seemed to be a tendency toward figurative expression in his paintings. Critics noticed and praised his mixture of modern Occidental techniques and Oriental mystical subject matter, borrowing from the European post-Cubist and Constructivist styles, while remaining essentially Chinese.[12] Viewed by Parisian critics, Gee’s work could be exotic, very Chinese, composed with oil painting techniques that they were familiar with.

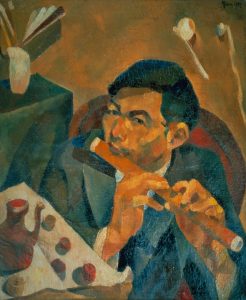

The Flute Player (Self-Portrait)

The Flute Player (Self-Portrait)

1928

oil on canvas

23 x 19 inches

One can also observe a few canvas paintings of Gee’s self-portraits during this period to see the artist’s varying views of himself. In Flute Player (1928), he is dressed in a modern Western suit, and playing a Chinese flute, along with a few other objects to show some of his favorite things, such as a wine pot, books and a pipe. With the overall dark tones of The Blue Yun (1929), Gee is depicted wearing a broad brimmed hat with a cigarette in his mouth. The artist’s facial expression is seemingly much more mature and sophisticated than his actual age. In The Charm of Music (1930), Gee is shown wearing a traditional long Chinese men’s robe, and playing a Yangqin, a Chinese dulcimer, with bamboo sticks. The figurative style of these works is far from his early paintings that are primarily constructed by abstract forms of colors. Gee seemed to be content with his role as a cultural ambassador of the blending of Eastern and Western art.

New York Period

The racial conflict brewing in France sadly reminded Gee of the racial discrimination that he had experienced in San Francisco, which made him leave Paris even though his shows were successful and he had good reviews. The anti-Chinese sentiment was not as intense as in San Francisco, but he did not desire to stay in Paris and decided to settle in New York. The reason he chose to come to New York could be that the East Coast is closer to Paris and he might have expected to receive the same attention and recognition in the New York art scene as he did in Paris.[13]

Gee first stayed in New York from 1930 to 1936. Although his paintings were included in large group exhibitions held at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 1931 and at the Museum of Modern Art in 1932, he struggled greatly throughout the Depression. Gee might have gained some reputation in the Chinese community, but he was unable to secure financial support among the Chinese in New York due to the low economic situation in Chinatown and the high unemployment rate everywhere.[14]

Linda Darnell

Linda Darnell

1951

oil on canvas

36 5/8 x 41 7/8 inches

Gee resettled once more in New York in 1939 until his death in 1963. In 1940, he resided on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, and later moved downtown to 10th Street.[15] In 1944, his work was included in a group exhibition, “Portrait of America,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He also taught painting classes and wrote his innovative art theory of “Diamondism”. His later paintings are more figurative, with diverse motifs. The figures in his work are emphasized by the sculptural volume of their body as in Two Women (n.d.) and Hospital Court (1951). In Linda Darnell (1951), the subject is depicted figuratively in detail and its pictorial composition shows his delicate design for lighting effect. The reflected wallpaper seen in the mirror has patterns that are composed of triangular color forms, which come from the pictorial elements in his early paintings but with more tender and similar tones.

As Gee had experienced before, his exhibitions in New York did not receive as warm a reception or appreciation as compared to the ones he had in Paris. The curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art explained that they could only accept works that were painted like Van Gogh, Renoir or Cézanne. Therefore, he retreated from showing in America. In Gee’s opinion, the reason why American Art was not moving forward was because it was dominated by academicians. It was as if they had a rope around the artists’ necks. American artists only became well-known through the influences of academic institutions and commercial and practical factors. Artists were making art by following popular trends, instead of searching for the truth of their own characters and aesthetic values.[16]

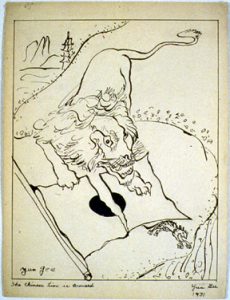

The Chinese Lion is Aroused

The Chinese Lion is Aroused

1931

ink on paper

11 1/2 x 8 3/4 inches

Gee’s financial situation was difficult in his latter years. Even under these circumstances, he generously helped with the floods and shortage of food in his native China. He also donated paintings and organized fundraising exhibitions for the disasters. He made political comics to satirize current events. The Chinese Lion is Aroused (1931) showed his hopes that China would become powerful very soon. His desire to make people aware of the cruel crime committed by the Japanese was explicated in Peace to China (1942). Sinking Empire (1942) demonstrated his criticism on the Japanese invasion of China as well as his prediction of Japanese failure. Although Yun Gee lived in New York, he was always concerned about China.

In 1979, “The Paintings of Yun Gee,” a touring exhibition organized by The William Benton Museum of Art, CT, U.S.A., provided an opportunity for scholars and historians to become aware of the significance of Yun Gee’s work in Asian American art history, especially how he was first established in the West Coast. His life story is often regarded as a case study on how Chinese immigrants and American artists of color in the early Twentieth Century aspired to participate in the American art community.[17] Considered within the field of cultural studies, Yun Gee was a “transnational in ‘in between’ spaces”. Throughout his career, he explored many cultures and embraced their different aspects in his paintings.[18] In 1992, the exhibition of “The Art of Yun Gee,” organized by the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, introduced Gee’s work and his achievements to the audience in Asia. Although in his later years, Gee was not active in the New York scene, his art finally gained long overdue recognition through research and exhibitions.

Tung Hsiao Chou is an art historian, writer, translator and archivist. Her art reviews and essays have been published in major art journals and exhibition catalogues.

[1] In 1922, Gee Quong On’s address was #37 Spoffard Alley, San Francisco. In 1923, Yun Gee’s address was 822 Clay Street, San Francisco. The second location seems to be only one block away from the first one. See Yun Gee Archives. Collection of Li-lan.

[2] See Anthony W. Lee, “Introduction,” in Yun Gee: Poetry, Writings, Art, Memories, ed. Anthony W. Lee (Seattle, W.A.: University of Washington Press, 2003), pp. 3-18.

[3] See Yun Gee, “Yun Gee Biography and Criticism (Outline),” n.d., pp. 6-7. Yun Gee Archives.

[4] See Chia Chi Jason Wang, “Yun Gee and China,” Yun Gee exhibition catalogue (Taipei: Lin & Keng Gallery, 1998), pp. 9-15. Robert E. Jr. Harrist, “San Francisco, Paris, and New York: Works by Yun Gee from 1926-1933,” A Minimal Vision exhibition catalogue (New York, N.Y.: Chambers Fine Art, 2002), pp. 65-73. My essay “Yun Gee’s Early Paintings and Life Journey: Special Exhibition A Minimal Vision of His Portraits’ World,” (Taipei: Artist Magazine, June 2002), no. 325, pp. 256-269.

[5] See Mary Braggiotti, “He Paints the ‘Inner Man’,” New York Post, October 26, 1943. Yun Gee Archives.

[6] See Reuben H. Menken, “Yun Gee Biographical Sketch,” n.d., Yun Gee Archives.

[7] In 1938, his address was “3 Rue des Carmero, Hotel Voltaire, Paris 5e”. In 1939, his address was “9 Rue Delambre, Paris 14e . See note 1.

[8] See note 6.

[9] See Pierre Mille, “Yun Gee,” 1939. Yun Gee Archives. Reprinted in Yun Gee: Poetry, Writings, Art, Memories, pp. 161-62.

[10] See Gee, “Yun Gee Biography and Criticism,” n.d., p.10. Yun Gee Archives.

[11] See Gee, “East and West Meet in Paris,” 1944. Yun Gee Archives. Reprinted in Yun Gee: Poetry, Writings, Art, Memories, pp. 181-82.

[12] See Le Veilleur, “Yun Gee at the Reine Margot,” Les Heures de Paris, April 6,1938. Charles Fegal, “Yun Gee,” La Semaine A Paris, March 30, 1938. Yun Gee Archives.

[13] See Lee, “Revolution in Art and Life,” Yun Gee: Poetry, Writings, Art, Memories, pp. 131-33.

[14] See David Teh-yu Wang, “The Art of Yun Gee Before 1936,” The Art of Yun Gee exhibition catalogue, (Taipei: Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 1992), p. 31.

[15] In February 1940, Yun Gee lived at 24 East 67th Street, New York City. Since the 1940s, he lived at 51 East 10th Street, New York 3, NY. See note 1.

[16] See Gee, “Letter to Paul Bird,” 1951.Yun Gee Archives. Reprinted in Yun Gee: Poetry, Writings, Art, Memories, pp. 183-85.

[17] See Paul Karlstrom, “A Modernist Painter’s Journey in America,” Yun Gee: Poetry, Writings, Art, Memories, pp. 21-34.

[18] See Joyce Broadsky, Experiences of Passage: The Paintings of Yun Gee and Li-lan, (Seattle, W.A.: University of Washington Press, 2008)

•BACK•