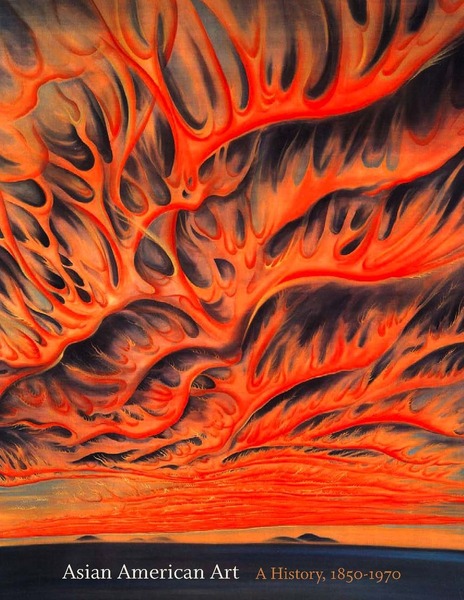

Asian American Art – A History, 1850-1970

The natural path of emigration from Asia to the United States is across the Pacific Ocean. Consequently, the most populous concentrations of Asian immigrants have been on the West Coast, with important centers in Los Angeles and San Francisco, as well as in Seattle and Portland. After coming to the West Coast, relatively few who arrived from Asia continued eastward, which is true for artists as well as for other members of the community. But New York in the final decades of the nineteenth century became the artistic capital of the country, a role it fulfilled throughout the entire twentieth century. It is also a city of great visual dynamism: “I enjoy sketching in the asphalt jungle – the big city,” wrote Dong Kingman, who achieved success as an artist in San Francisco and the moved to New York for the rest of his career. Lured by New York’s energy and sophistication, some of the most ambitious Asian American artists relocated to this artistic center, and the history of their accomplishments has yet to be written.

This essay surveys the works and careers of a number of the most interesting of these artists, concentration on the little-studied but dynamic years of the first half of the twentieth century. Some of the artists were born here; many came from Asia. They were adventuresome, independent people who traveled extensively. Many paid extended visits to Paris, the center of modernism, and several returned to Asia for the concluding phases of their careers.

The artists who came from Asia brought their native traditions with them into their new country where, for much of the twentieth century, they were discriminated against and not permitted to become citizens. In their writings, often in the titles themselves, they frequently acknowledged their dual identities. Yasuo Kunihyoshi’s major autobiographical essay was titled “East to West.” Yun Gee wrote an essay about his years in France called “East and West Meet in Paris.” Isamu Noguchi, who was born in the United States but spent his youth in Japan, wrote in A Sculptor’s World, his autobiographical memoir, “With my double nationality and double upbringing, where was my home?” The painters manifested this doubleness in their work in several ways. They were comfortable with the technique of Asian art, particularly water-soluble black ink applied to paper with brushes; living in the West, they also learned the European technique of oil on canvas. Yun Gee, for one, saw himself adopting this new method to revitalize the Asian artistic traditions he knew from his youth:

I had studied watercolor painting in China under the master Chu, and having learned the techniques of the Chinese masters I naturally desired to become acquainted with the masters of the West. Through the museums and galleries my eyes were soon opened to their great achievements and to the unlimited possibilities of painting in oil. Observing the similarities and dissimilarities between the art of the two cultures, I determined to create a technique and philosophy of art which would transcend the differences of bridge the gap.

Most of these artists attended art schools in the United States, and their art reveals a dialog between Euro-American concepts of space and from and Asian practices. Sometimes they adhered to Western models of the three-dimensional forms modeled in light and shade set in a perspectival space, but at other times they favored flatter images. Beyond technique and form, subject matter was an area in which these artists could express their Asian identities. Also, they sometimes signed their works with their Asian names or inscribed texts in Asian languages on their pieces. These practices took place in a fluid and shifting field, particularly as they were available to Euro-American artists as well: the adoption of Asian effects by non-Asian artists was widespread from the late nineteenth century on, and modernist painting’s embrace of the two-dimensional surface was encouraged by Asian prototypes. Still, allusions to Asian traditions were more commonly made by artists of Asian descent, who affirmed their origins by reflecting them in their works. It is not unusual to find a spectrum of effects in the lifework of an Asian American artist; some pieces seem entirely Western, while others actively incorporate Asian references. For example, take Chuzo Tamotsu, who left his native Japan to spend six years exploring Europe before setting in New York from 120 to 1941, and then moving to New Mexico. The prints he made in New York under the auspices of the Works Projects Administration include East 13th Street. Here he depicted kids frolicking in the water from a fire hydrant on a city street, an American subject typical of the urban realist style then prevalent in New York. He adopted an American style and a technique foreign to Asian artistic traditions, lithography. Later, in the mid-1950s, he made a series of linocuts of horses, timeless subjects not particularly modern or urban, and he used the block-print technique to evoke Japanese woodcuts and brush-and-ink drawings. In the East 13th Street print he carefully shaded the forms with small strokes of the lithographic crayon; in the later block print he carved his image with a few quick, dramatic strokes, and signed the print with a red seal, or chop, an Asian practice. Here East meets West not as an artistic fusion in a single work, but as alternative traditions called up in separate works by the same artist.

At this step of my research I have discovered little about Asian American artists active on the East Coast in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, although they were already visible on the West Coast. Those who did come to New York found a receptive cultural climate due to the enthusiasm for Japanese art and culture that had developed in the late nineteenth century. Artist Arthur Wesley Dow, one of the main popularizers of that vogue, was a famous teacher and had many disciples. In 1899, he published his vastly successful book, Composition, which he claimed was based on principles derived from Japanese art. Art critic Sadakichi Hartman was an important member of the avant-garde circle around Alfred Stieglitz. He was half German and half Japanese, and his multicultural heritage was reflected in his writings. In the early years of the century, he published a pair of contemporary books, Japanese Art and History of American Art, and at various times in his career he wrote three plays titled Buddha, Confucius, and Christ.

By the late 1910s, ambitious Japanese artists in New York started banding together in groups to hold exhibitions, and one can get a sense of their activities, although much has been lost. This area of art historical investigation is fairly new, and the writing about it has mostly been done in Japan, which is true of the collecting of the art as well.

The Japanese artists in New York supported each other as friends with a shared heritage at the same time as they were involved with the larger art scene. Their sense of community was manifested in the group exhibitions they organized. A show held in 1917 was titled Young Japanese Artists in New York, at the Yamanaka Galleries on Fifth Avenue. It featured ten artists, including T.K. Gado, who made some remarkable paintings in New York in the early 1920s that have recently come to light. While most of the Japanese artists working in New York in this period studied at the Art Students League and painted fairly straightforward scenes of urban life, Gado plunged into a radically modernist style with paintings such as Subway (also known as Communication in the Under Surface) (1923). The painting recalls Max Weber’s avant-garde Rush Hour, New York from 1915, but it is even more frenetic in its futuristic evocation of the jostling dynamism of the subway, as the artist combines a pulsating surface with a plunging space, representing the human energy of the metropolis at its peak. Gado graduated from the Tokyo University of Art before coming to the United States, and he returned to Japan in 1924. While in New York, he worked as a designer for export china, and only about a dozen works in this ambitious modernist style are believed to exist today.

In New York, Gado showed his paintings annually with the Society of Independent Artists, which began its revolutionary series of nonjuried exhibitions in 1917. Japanese artists were frequent participants. The exhibitions at the Society of Independent Artists were complemented by the open exhibitions at the MacDowell Club, where any self-organized group of artists could rent the gallery for a nominal fee and hold a two-week show. In 1918, a dozen Japanese artists exhibited at MacDowell, calling themselves the Japanese Art Association. This show included Yasuo Kuniyoshi, who had made his exhibiting debut the previous year at the inaugural exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, and who would become one of the most prominent painters, Asian or otherwise, in the United States in the decades between the two world wars.

A photograph of the artists who exhibited as the Japanese Artists Society in 1922 is symptomatic of the state of research: although we know the names of the exhibitors, today only five of the twelve artists pictured can be identified. By 1922 a group of artists had developed who would periodically show together through the 1930s. Artists would come and go, but usually participants included Kuniyoshi, Kyohei Inukai, Eitaro Ishigaki, Gozo Kawamura, Toshi Shimizu, Kiyoshi Shimizu, Chuzo Tamotsu, Bumpei Usui, and Torajiro Watanabe.

Another group show, The First Annual Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture by Japanese Artists in New York, held at The Art Center on East Fifty-sixth Street in early 1927, included many of the same artists. Again, a formal photograph documents the occasion but in this picture Kuniyoshi has moved from the far right to the center, a position befitting his rising status in the New York art world.

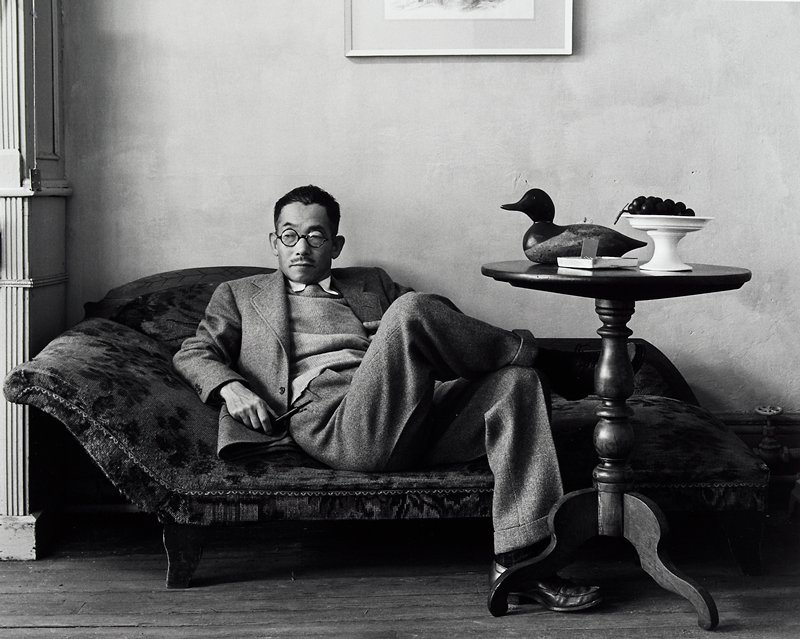

The acclaim Kuniyoshi achieved was an even greater accomplishment considering he came to the United States alone in 1906, barely seventeen years old, with the idea of making money and no intention of becoming an artist. A year later he moved from Seattle to Los Angeles, finding unskilled jobs to support himself. In Los Angeles he took the advice of a high school teacher who encouraged him to study art. In 1910 he moved to New York City, where he tried out several progressive art schools until he found a place he felt happy, the Art Students League. The league, which is still active today, appealed to many immigrant artists because of its liberal structure: no entrance requirements, no mandatory attendance, no examinations, no diplomas, and no degrees. The theory was, if students were serious about becoming artists, they would provide their own discipline. The faculty included prominent academic painters as well as the leaders of the socially concerned Ashcan school, Robert Henri, John Sloan, and George Bellows, who influenced many of the Japanese immigrant artists. Kuniyoshi studied at the league from 1916 to 1920 and then returned as a teacher in 1933.

Critics writing about Kuniyoshi’s art commonly referred to an “Oriental” quality in his work, usually without getting specific about what they meant. Their vagueness was due in part to the originality and the weirdness of his paintings, particularly in the 1920s, when he made his reputation, and invented such peculiar subjects as Boy Stealing Fruit and Al Perkins Drying Fish. The artist himself claimed that his aim was to bring together East and West, and Asian references are particularly marked in a series of highly finished black-ink drawings he made in the 1920s. Fisherman (1924) is a whimsical scene drawn in the traditional Asian technique of black ink on paper. The fisherman emerges from a floating nonperspectival space to grab a fish. Below him is a collection of sea creatures, common subjects in the art of Japan, an island nation. In the far background the artist placed a mountain peak that hovers above the earth, a motif common in Chinese and Japanese landscape painting.

Kuniyoshi took two extended trips to Paris, in 1925 and 1928. They resulted in a change in his style, from painting from his imagination to painting from the model, from flat space, “like kakemonos,” to perspective space. From the late 1920s to the mid-1940s he produced some of his best-known paintings, of brooding, scantily dressed women. In the backgrounds of many of these, such as I’m Tired (1938), he developed beautiful passages of swirling, impasto pigment that reveal his fascination with the sensuality of oil paint. These paintings have encouraged some writers to see him as a totally Westernized artist, a view that ignores pieces such as his ink drawings, which, with their high degree of finish, stand as independent works of art, as they would in China or Japan. In his own words, his aim as an artist was “to combine the rich traditions of the East with my accumulative experiences and viewpoint of the West.” Even his most Parisian paintings, American critics felt, contained something Asian in their “refinement,” but when Kuniyoshi took his only trip back to Japan in 1931 to visit his ailing father, the Japanese art community greeted his work as Western. Still, at his most Europeanized, working with perspective and oil paint, he sometimes chose themes like Japanese Toy Tiger and Odd Object (1932), whose subject refers to Asia.

After World War II, Kuniyoshi entered the last phase of his artistic career. He brightened his palette and developed a shallow, layered space in what he saw as a fusion of his early and middle periods, “to paint ideas as in his early work but with the feeling of reality of his middle work.” And he continued to include Asian references in his subjects – his last painting was Oriental Presents (1951) – before concluding his career with a series of dark, grim sumi-e ink paintings.

Although Kuniyoshi was the most prominent Asian American artist of his time in terms of recognition and prestige, others of his Japanese friends in New York were active in the art world, making paintings that look very interesting today. Those friends include Toshi Shimizu and Eitaro Ishigaki, whose works and documents have been preserved in Japanese museums, so more information is available about them than about some of their peers.

Toshi’s brother, Kiyoshi, for example, regularly exhibited paintings of New York street scenes with the Japanese American groups and with the Society of Independent Artists in the 1920s and 1930s, but his paintings are dispersed and little is known about his career today. In contrast, the works of Toshi, who returned to Japan and the bulk of whose paintings are in the museum of his native prefecture, can be studied in several publications.

Toshi Shimizu came to the United States in 1907 at the age of twenty, intending to raise money to study art in Paris. Instead, he studied in Seattle with Fokko Tadama, a Dutch painter of academic persuasion who had several Japanese students (see Kazuko Nakane’s essay for more information). In 1917, Shimizu moved to New York, where he studied at the Art Students League and worked as a painter before moving to Paris in 1924. He spent three years there before returning to Japan. At the Art Students League, Shimizu befriended John Sloan, the urban realist painter who was also the president of the Society of Independent Artists, where Shimizu and many of his Japanese contemporaries exhibited their works. Shimizu adopted the ideals of the Ashcan school artists, who believed in painting realistic scenes of everyday life in the city. He depicted the sidewalks of New York crowded with their busy vegetable markets, shoppers, and beggars. His slightly caricatured figures were painted loosely, with a keen eye for costume as an indicator of social and economic class. But when he looked at urban reality, he saw more Asian figures and subjects than did the American artists who inspired him. Robert Henri, the leader of the Ashcan school, created some portraits of Asians as part of his democratic program to depict all types of people, and Sloan painted one, Chinese Restaurant (1909). But Sloan’s Chinese Restaurant, where an attractive Caucasian woman in a plumed hat plays with a cat, could be any restaurant. When Shimizu painted the same subject in 1918, a Chinese waiter was prominently included along with white sailors and their women.

In 1919, Shimizu interrupted his stay in New York to return to Japan and get married. This trip resulted in several paintings in which he applied his urban realist style to Japanese subjects, including Yokohama Night (1921), painted from an elevated point of view with dozens of figures going about their varied activities. He showed it first at the Independents and then at the Art Institute of Chicago, where it won a prize that was subsequently revoked because he was not an American citizen. The American Art News account of the episode was titled “Chicago Overrules Jury and Bars Jap.” Similar alienating stories come up repeatedly in the careers of Asian immigrant artists: by law, they were not permitted to become American citizens, and their lack of citizenship then became an excuse to further exclude them.

Back in New York, Shimizu painted New York, Chinatown at Night (1922) from a high point of view like that in Yokohama Night, its deep urban space filled with fifty-six figures, including a 1920s version of the tour buses that still prowl through Chinatown today. Here he took the bustling Lower East Side setting loved by Ashcan school artists like Bellows and George Luks and relocated it a few blocks west, replacing the immigrants from Easter Europe with immigrants from Asia. After he moved to Paris, he continued to paint urban realist subjects, but his style gradually stiffened and started becoming more abstract. In Shimizu’s Merry-Go-Round (1925), a subject popularized by urban realist Reginald Marsh, the child riding the carousel horse is Asian. When Shimizu turned to the definitively modern subject of the movie theater, he continued a subject explored by Sloan in Movies, Five Cents from 1907, echoing Sloan’s diagonal view of the people watching the film. Both Sloan’s and Shimizu’s paintings anticipate Edward Hopper’s famous New York Movie of 1939, but unlike Sloan and Hopper, Shimizu included an Asian parent and child in the theater audience.

His tendency toward abstraction continued after he returned to Japan in 1927. But as Japan became more militarily aggressive, Shimizu joined some of his contemporaries – most famously Tsugouharu Foujita, who had returned to Japan from Paris in 1933 – in painting monumental, realist military paintings such as Charge! (1943 that, despite being painted in anti-Western wartime Japan, were modeled on nineteenth-century European history paintings.

While Shimizu was in Japan painting scenes of war, Eitaro Ishigaki was in New York making art that protested Japanese militarism. He had been summoned to the United States by his father, who had immigrated after losing his job as a carpenter when the whaling business in Japan declined. After working at menial jobs on the West Coast, Ishigaki began studying art in 1913 at William Best School of Art and then at the San Francisco Institute of Art. He also became interested in socialism, encouraged by Sen Katayama, a founder of the Communist parties in Japan and the United States.

In 1915 Ishigaki moved to New York, where he, like Shimizu, studied with John Sloan at the Art Students League. His works alternated between scenes of street life in New York and paintings with political themes, peopled with muscular, struggling figures, sometimes nude, that evoke Michelangelo’s paintings as well as those of the Mexican muralists then active in the United States. The Man with the Whip from 1925 is a powerful early example, though the geometrical stylization of the figures is more modernist than usual for the artist. Much of its tension derives from the contrast between cubist angles and art-nouveau curves. These create a conflicted image of a whip-bearing man on horseback who represents the oppressive forces of capitalism as he dominates a crowd of faceless workers set against a backdrop of the factories where they are forced to labor.

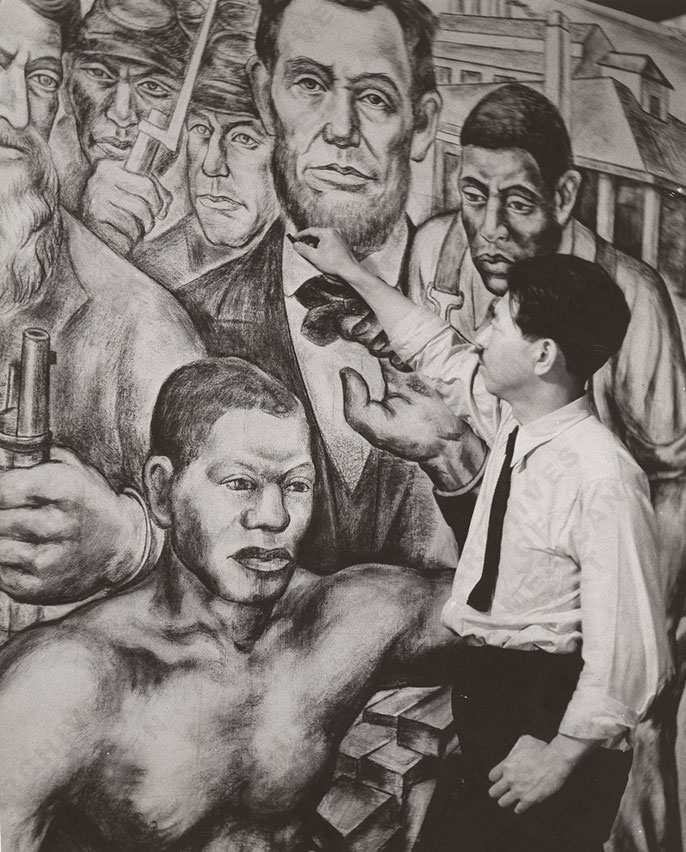

Ishigaki was active in left-wing groups an in 1929 was a founding member of the John Reed Club. During the Depression he painted two ambitious murals for a courthouse in Harlem, The Independence of America and The Emancipation of the Slaves. Although patriotic, they were still controversial. In each six-by-ten-foot painting Ishigaki juxtaposed a static group of portraits of American heroes with active figures, all larger than life-sized. In one scene the enacted the American Revolution, and in the other, the oppression and freeing of slaves. His portrait of George Washington was criticized as making him look “cruel,” although it was clearly based on Gilbert Stuart’s eighteenth-century portraits. Emancipation of the slaves was still a volatile subject in the 1930s, and Ishigaki’s portrait of Abraham Lincoln was criticized for being too negroid in its features and skin color – a troubling critique. The Municipal Art Commission in charge of the job removed the paintings due to the controversy, and they were eventually destroyed.

Ishigaki was a tempting target for racist critics because he had already established himself as a dedicated leftist artist who in 1931 painted Lynching, a dark and violent condemnation of racial murder. In 1935, there were two exhibitions in New York protesting lynchings, one organized by the NAACP and one at the ACA Gallery, the leftist gallery where Ishigaki would have solo shows in 1936 and again in 1940. Although Ishigaki did not take part in either of the two anti-lynching exhibitions, his painting foreshadows many of the works shown there. Lynching stands apart, however, in the prominence Ishigaki gave to the women in the mob. They are in the foreground, illuminated by a lantern that makes them visible against the dark surroundings, and one holds the lethal rope.

The prevalence of active female protagonists is characteristic of Ishigaki’s art, suggesting his desire for equality among all races extended to both genders, as the artist frequently portrayed powerful women. In his Harlem Independence mural, a woman led the revolutionaries below Washington and Franklin, reminiscent of Delacroix’s Liberty at the Barricades. Later in the decade, when he made paintings protesting the rise of fascist militarism, Ishigaki’s images of Basque women throwing around Italian men – such as Resistance, from 1937 – received a lot of attention in the press, and his 1948 Triumph of Women, in which women physically brutalize some victimized men, is an unusual image in the history of sexual politics. Ishigaki was married to a prominent journalist in the Asian American community, Ayako Ishigaki, who chronicled her rebellion against her traditional Japanese upbringing in her autobiography, The Restless Wave, published in 1940 under the pseudonym Haru Matsui and illustrated by her husband. In these graceful illustrations Ishigaki exhibited the artistic dualism that is characteristic of many of the artists discussed here. He was one of the most Westernized of the Japanese American painters working in New York. But when he turned to illustrate his wife’s autobiography, he put away his oil paints and switched to brush and black ink to represent ikebana arrangements, Japanese lanterns, and women in kimonos, which evoked his and his wife’s youth in Japan.

The controversy about Ishigaki’s Harlem murals was complicated by the fact that after two years of work he was removed from the project, and it was finished by assistants. The murals were commissioned by the government’s Works Project Administration in 1935, and in 1937 it was decided that only American citizens were eligible for its aid, resulting in the dismissal of three thousand workers from the program. Once again Asian-born artists were discriminated against due to the laws that made it impossible for them to become citizens. This time some of them protested.

The 1930s in the United States, with the Depression at its worst, was a time of great political unrest, and the Communist Party and related leftist organizations were very active. Artists of Asian ancestry worked with liberal organizations like the American Artists Congress, perhaps because the left claimed to be color-blind. The Communist Party was trying to woo African Americas, and some conservatives feared an alliance between blacks and Asians. Kuniyoshi played a leading role, as an officer in the American Artists Congress before World War II, the president of An American Group, an done of the founders of the socially concerned ACA Gallery. After the war he was the founding president of Artists Equity, which is still active today supporting artist’s rights. When curator Lloyd Goodrich questioned Kuniyoshi about his political involvement, the artist’s response had less to do with specific issues than with the role of political engagement in his life. According to Goodrich, Kuniyoshi expressed an attitude that probably applied to his Japanese immigrant artist friends as well:

He spoke at some length and emphatically about how strongly he believes in such activity, and how much he feels it has done for him. He said that he has always given some time to such work, and that he feels that it has helped him develop. I got quite clearly the feeling that this has been very important to him in overcoming his feeling of being an alien; that it has helped a great deal to make him feel at home in America and to give him a sense of security and belonging.

In response to the WPA policy of firing non-citizens, the ACA Gallery held a series of three “pink-slip” exhibitions protesting the exclusion of Asian-born artists from the program. Here for the first time we find Chinese American artists emerging to join forces with the better-known Japanese Americans. The first exhibition opened just two weeks after the ban went into effect and featured more than seventy artists, almost twenty of whom were of Asian ancestry. The last, in September 1937, was sponsored by the Artists Union of the American Artists Congress; it included only artists of Asian descent and served as a survey of Asian Americans in the New York art world at the time. They were united in their opposition to the WPA cuts, but they also had another bond: their antagonism toward Japanese military aggression in China.

In reviews of the show, several critics praised the collaboration of artists from two nations that were at war with each other. Most of the Japanese artists in New York were liberal in their politics and opposed Japan’s military ambitions, giving them common ground with the Chinese artists. Still, tensions did exist, as Emily Genauer mentioned in a series of insightful remarks about the ACA show. She indicated Kuniyoshi’s influential status as well as the relative scarcity of Chinese artists working in New York’s art world:

Outside of the pictures themselves there are several aspects of the show that are interesting. One is the fact that some of the Japanese were loath to submerge their intense nationalism and exhibit in the same show with Chinese artists. Another is that there are so few Chinese painters, comparatively, in New York, and that their work is so much more academic than that of the Japanese. Still a third angle is the homogeneity of the Japanese artists’ work as contrasted with that of the Chinese. It is difficult to say whether they all paint with something approaching the unique brushwork and coloring of Kuniyoshi because that approach is singularly Japanese, or because Kuniyoshi, today considered one of America’s most important painters, is their mode.

The names of a few Chinese artists working in New York have come down to us, thanks to reviews of these shows, but so far their works are not known. Chu H. Jor, C.W. Young, and Don Gook Wu were cited by Melville Upton in the New York Sun, who felt they were “under Western influence.” Wu seems to have made the greatest impression on the critics in the three “pink-slip” shows, as he is mentioned most frequently; Jacob Kainen described his Unlovely Sunset as “wild Expressionism a la Orient.”

Chu H. Jor was active in Chinatown and founded the Chinese Art Club, which began in 1935 on Pell Street and then moved for several years to 175 Canal Street. The purpose of the club was to encourage young artists and art appreciation, and “to introduce Chinese artists to the American public and Occidental arts to the Chinese public.” The club held a series of exhibitions in the late 1930s, featuring works by Chinese artists plus some by non-Chinese. There were several shows of children’s art as well as of photography, and the art shows featured examples of the Chinese-style painting, including those by Yee Ching-chih, who offered classes in Chinese painting at the club. But most of the works were Western in style, probably including those of Jor, whose paintings are unknown today but who studied with American art teachers such as George Bridgman and Dimitri Romanovsky from the Art Students League.

The Japanese artists most frequently singled out in reviews of the “pink-slip” shows, other than Kuniyoshi, were Chuzo Tamotsu, Eitaro Ishigaki, and Sakari Susuki. Susuki, like several of his peers, was born in Japan and studied art in San Francisco before moving to New York. In 1936 at the Willard Parker Hospital in New York City he painted a mural illustrating medical achievements, with monumental figures reminiscent of Diego Rivera’s; the building was subsequently torn down. He also showed in group exhibitions, where his work was frequently described as “Surrealist.” His War, reproduced in a 1937 newspaper, is a monumental composition, again recalling Rivera’s influential style. Densely packed soldiers surround a triumphant, leering skeleton in extravagant military garb. The painting was shown at an ambitious exhibition organized by the American Artists Congress titled In Defense of Democracy: Dedicated to the Peoples of Spain and China. Held at a rented loft space on Fifth Avenue in December 1937, the show featured two hundred artists. Several critics emphasized the conflict between propaganda and artistic quality, while singling out a few artists as succeeding with both, like Ishigaki with his Flight painting about victimized Chinese and Philip Guston with his powerful Bombardment tondo. The exhibition was supplemented by a meeting of the artists’ congress, which included the reading of anti-fascist statements by Thomas Mann and Picasso, whose etching Dream and Lie of Franco was included in the show. Kuniyoshi was one of the artists who made a speech before the congress; he spoke about the rights of Asian American artists in the United States.

During this period of activism, Herman Baron, the director of the ACA Gallery, continued his gallery’s commitment to political art by hosting an international traveling exhibition of graphic art by contemporary Chinese artists in January 1938. Jack Chen (Chen I-wan), the artist who organized the show, contributed black-and-white works, one depicting a proud Communist soldier and another of a Chinese peasant grimly squatting beside a dead child, a rifle at his side for his future combat with the Japanese. Works with similar themes were again exhibited in March at the Chinese Art Club in a show dedicated to “the Chinese struggle against Japanese aggression,” which included a drawing of a woman volunteer by Jack Chen and a watercolor of a refugee by Moo-Wee Tiam, who was then president of the club. However, a reviewer pointed out that the show as composed mostly of conventional still lifes, landscapes, and figure paintings, with only five pieces having a direct political thrust.

When Japanese artists living in New York put together an exhibition at the Municipal Art Gallery in June 1938, pro-Chinese subjects were again visible, particularly in the works of the militant Ishigaki. But the paintings of many of these artists were not overtly political, as exemplified by the work of Kuniyoshi; he, however, took a firm stance against Japanese militarism in his public statements, and in his willingness to loan works to leftist exhibitions. As the international situation worsened, rifts developed in the American Artists Congress, between those who advocated total adherence to the Soviet party line and those who insisted on independence from it. With the signing of the Hitler-Stalin Non-aggression Pact in August 1939, the split intensified until the congress became ineffectual as a voice for liberal artists.

After the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the situation for Japanese ancestry artists transformed terribly. Kuniyoshi wrote, “A few short days have changed my status in this country although I myself have not changed at all.” The government confiscated his telescope and camera. His bank account was impounded, and he had to fill out papers to travel from his studio on Fourteenth Street to his summer home in Woodstock, New York. Since he was on the East Coast, not in one of the areas designated to send Japanese to internment camps, he was spared imprisonment.

Kuniyoshi believed strongly in the democratic system, which had allowed him to rise to success, and her firmly opposed Japanese military aggression. He organized a retrospective surveying his career; proceeds from the admission charge and the raffle of one of his paintings went to China relief. Although he could not be included in the huge Artists for Victory exhibition oat the Metropolitan Museum because he was not a citizen, he worked for the Office of War Information, making two pro-democracy radio speeches that were broadcast to Japan and a series of propaganda drawings. In a speech on the second anniversary of Pearl Harbor, Kuniyoshi said,

I know the sting of segregation and the look that condemns one as an enemy. But after the initial confusion and excitement had subsided a more lenient attitude evolved. Democracy has prevailed in this country despite global chaos.

In 1944 he won the first prize in the annual Carnegie survey of contemporary art, despite being a Japanese citizen, and he felt “to have received the prize at this crucial stage of the war seemed almost beyond belief.”

Only one poster was made from Kuniyoshi’s sketches for the war effort, but his propaganda drawings contain a level of violence foreign to his earlier work and reflect the crisis he was facing. They include images of Japanese soldiers brutalizing nuns and babies, and of a huge hand holding a bag full of symbols of Japan, such as a samurai sword and the national flag, about to dump it. Following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasiaki at the end of the war, he immediately went to work to help people in Japan and Japanese Americans who were being resettled following internment.

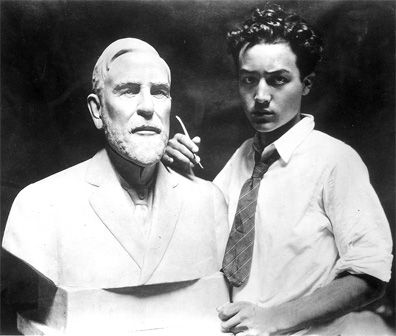

Other Japanese artists of the time, like Tamotsu, included similar symbols in their art – as did Yun Gee, who was of Chinese descent. Gee came to New York in 1930 and started participating in pro-China efforts soon after Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931. Today Gee is the best-known Chinese American artist active in the first half of the twentieth century, appreciated especially for the strikingly modernist paintings he made in San Francisco in the 1920s. He immigrated to California in 1921 at age fifteen, summoned by his father, who was able to get him American citizenship. There he studied painting and developed his synchromist-related style, building up images from geometrical planes of vivid color. After he achieved some success in San Francisco, and organized the Chinese Revolutionary Artists Club, patrons invited him to Paris, where he soon found venues to exhibit his art. In Paris he added expressionist distortions to his cubist-derived modernism and drew on Chinese cultural history to represent figures such as Confucius and Lao-Tse. After three years he moved to New York in an attempt to make money to support his new French wife. There he immediately started showing his work in galleries and at the Museum of Modern Art, and was also active in pro-Chinese demonstrations. He lived in bohemian Greenwich Village and had contact with nearby Chinatown, painting actors from the Chinese theater and performing Chinese music at such places as the University Settlement House. When parts of China were menaced by massive floods in 1931, Gee painted a seventeen-foot-long mural as a benefit for flood victims. The mural, now lost, was installed on the façade of a public school on Mott Street, the central artery of Chinatown. Gee painted a long, scroll-like scene of floodwaters with figures in Chinese dress floating in front of the shallow space.

As Japanese aggression against China intensified in the 1930s, Gee made political cartoons for Chinese newspapers. In one, a Japanese soldier stands over a field of dead bodies, the same imagery that Kuniyoshi used in some of his World War II drawings. The conflict also inspired several of Gee’s paintings, including one shown at the leftist John Reed Club, which had been founded in part by Ishigaki. In his Tanaka Memorial, Japanese Imperial Dream (1932), Gee crated a bizarre scene of swirling, nightmarish space and figures that combine elements of cubist geometry with expressionist distortion. The subject is somewhat obscure today – it refers to a notorious letter from Prime Minister Tanaka to Emperor Hirohito outlining a plan for Japanese military conquest of the world. In the painting, Tanaka kneels before three figures: the emperor, the empress (who is brazenly naked except for her crown), and a Buddhist monk. Tanaka gestures up toward his vision: three figures representing China, Russia, and the United States who are surrounded by Japanese warriors wielding samurai swords. A decade later the Japanese soldier at the upper right, swinging his sword behind the back of the United States, could have been seen as a prophecy of the surprise bombing of Pearl Harbor.

While Gee’s political imagery paralleled that of contemporary Japanese immigrant artists, signs of competitiveness were evident, as Gee indicated in 1931: “My attitude towards the Japanese artists as Kuniyoshi, Foujita and others is that of most Chinese towards the Japanese; that of a grandfather to a grandson.” Gee returned to Paris in 1936 and stayed for three years and then came back to New York, where he spent the rest of his life. In those late years he showed his work infrequently, and his production from the period has received little attention.

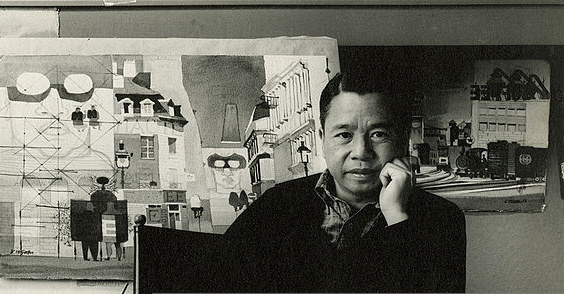

After Gee, the most celebrated Chinese American artist working in New York before the 1960s was Dong Kingman, who was born in Oakland in 1911 but spent his youth in Hong Kong. There he studied traditional Chinese painting and then returned to California. Like Gee, he made his reputation on the West Coast before moving to New York. As an American citizen, he benefited from having the WPA pay him to work on his painting during the Depression.

Kingman’s art was devoted to views of the modern urban landscape, and after he moved east in 1946 his main subject became New York. He almost never used oils, preferring watercolor, and his works are comparable to watercolors of New York scenes by John Marin and Edward Hopper. They also relate to the bustling city scenes painted by Mark Tobey, the Washington-based American artist who preferred water-soluble pigments on paper to oil on canvas, and who had an interest in Asian art. Kingman’s lively watercolors were widely published in books and magazines. His largest commission was for a mural on a wall of the Lingman Restaurant on Broadway and Ninety-fourth Street, for which he chose a scene of the New York harbor with a Chinese junk sailing through, in a tribute to his Asian heritage.

Kuniyoshi’s status was underlined in 1948 when he was given the first-ever solo retrospective of a living artist at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Twenty years later the Whitney again honored a New York-based Asian American artist with a retrospective exhibition: the sculptor Isamu Noguchi. Noguchi’s dual identity is the subject of much of his writing, and of the writing about him. He was a legal citizen of both the United States and Japan, as he was born in the United States of an American mother and a Japanese father, a famous poet who rejected his firstborn son to return to Japan and have a Japanese family. While Noguchi’s career flourished in the 1950s and after, the period dominated by the abstract expressionist movement, his artistic beginnings were rooted in the milieu of the socially concerned artists working in New York in the 1930s.

When Noguchi was two, his mother moved with him to Japan to be near his father; when he was fourteen, she sent him back to Indiana for school. In 1922, he moved to New York, where he studied art and began to exhibit his works. He then moved to Paris in 1927 and worked for an influential period as assistant to the sculptor Constantin Brancusi. In the 1930s, Noguchi was based in New York, establishing himself as a sculptor. In 1936, he spent eight months in Mexico with the leftist muralists and executed in relief a large mural about Mexican history. Back in New York he supported himself making skillful portraits, while his sculpture became increasingly abstract. A few of his works were pointedly political in intent, while others were not. His Death (Lynched Figure) stands out because it is a major early piece, an image of suffering unusual for Noguchi. It appeared in both 1935 anti-lynching exhibitions mentioned earlier, and it paralleled Ishigaki’s painting Lynching (1931) in its opposition to racial persecution. To execute this piece, Noguchi moved to the Woodstock art colony, where Kuniyoshi had bought a house in 1932 and where Hideo Benjamin Noda, Sakari Suzuki, and Jack Chikamichi Yamasaki had shared a house in 1931.

Death (Lynched Figure) presents the contorted figure of a man hanging from a rope supported by a rectangular armature. It brutality shocked critics, particularly Henry McBride, who called it “a little Japanese mistake.” The figure was based on a photograph, published in the communist magazine Labor Defender, of African American George Hughes being lynched above a bonfire. Unlike most photographs of hangings, which showed the victims hanging limp in death, this one documented Hughes’s agony as he writhed to get away from the fire.

The Mexican muralist José Clement Orozco used the same photograph as the basis for a lithograph that was also shown in the New York anti-lynching shows, as both he and Noguchi selected an image that emphasized the sadistic cruelty of the act. By suspending the sculpture instead of having it stand on a base, Noguchi confronted spectators directly with the horrific figure. Although it is quite common now to hang sculptures, in the 1930s the practice was highly unusual. Perhaps only Giacommetti, in works like Suspended Ball (1930-1931), had utilized such an approach, and the examples from his work are much smaller in size than Noguchi’s shocking vision.

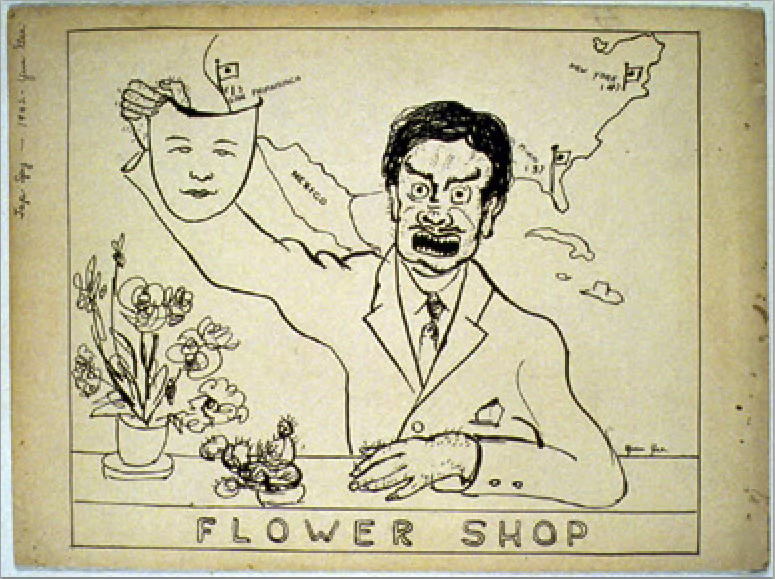

In the later 1930s, the political concerns of New York’s artists turned from lynching to the world situation, but the liberal views of progressive Asian American artists were not shared by all in Asian American communities. Ayako Ishigaki, the journalist wife of the artist Eitaro Ishigaki, wrote a distressed report before Pearl Harbor about Little Tokyo in Los Angeles, where Japanese newspapers defended Japan’s invasion of Manchuria. She attended a lecture by a visiting Japanese military officer that was greeted with such enthusiasm by the working-class crowd that they decided “to present an airplane to the Japanese Army, as a patriotic contribution from the Los Angeles Japanese.” The rapprochement between Chinese and Japanese artists in New York inspired by the WPA cuts seems to have shattered due to the outbreak of war in Asia, which created tensions and challenges among Asian Americans. This trouble is suggested in a cartoon by Yun Gee, who previously had protested anti-Chinese bigotry in his writings.

Titled Jap Spy, it depicts the proprietor of a flower shop who stands in front a map of the United States dotted with Japanese flags as he whips off a demure-looking mask to reveal a grimacing, pig-snouted face. Soon after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, internment camps were established for Japanese residing on the West Coast. Noguchi reacted quickly by volunteering to be interned at the Relocation Center in Poston, Arizona, hoping to help improve the conditions of those imprisoned there. After seven months, disappointed with his lack of progress, he managed to leave.

Following the war, Noguchi embarked on a life as a world traveler. His art was extraordinarily diverse, although consistently base on biomorphic forms, often in contrast with angular ones. He made freestanding sculptures in a wide range of materials and also extremely innovative garden environments. The latter were inspired in part by Japanese Zen gardens but commissioned by capitalist corporations: an example is his Sunken Garden for Chase Manhattan Plaza (1961-1964) in the financial district of New York City. In addition, he had a profitable career as a designer of lamps and furniture. By 1950 he had studios in both New York and Japan, and after his death in 1988 his home and studio in each country were turned into museums in his honor, continuing his dual legacy to the present.

Noguchi is generally considered part of the abstract expressionist generation of the 1950s that abandoned the social concerns and the representational imagery of the 1930s and 1940s in an attempt for a mythic, universal art. Young artists of Asian ancestry participated in this impulse. Typically they worked through various realist and modernist styles and then achieved a personal synthesis in an abstract mode that had a complicated relationship to the flat spaces of much traditional Asian art and to the Asian calligraphy. Several of the major abstract expressionists in New York, such as Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Franz Kline, painted in a spontaneous, gestural mode and made many paintings using only black and white. Consequently, the issue of their relationship to Asian calligraphy takes on an added resonance in the art of painters who have Asian ancestry.

In the later years of World War II, immigration restrictions affecting Asians were relaxed in the United States, and Asians entered the country in greater numbers. Thomas Messer and Anne Jenk’s 1958 exhibition, Contemporary Painters of Japanese Origin in America at the Boston Institute of Contemporary Art, showed eight painters working in a painterly, abstract mode the reflected the style developed by New York’s pioneering abstract expressionists a decade before. They included Kenzo Okada, whose softly contoured, delicately hued forms personified Asian “refinement” in the eyes of many critics, who also saw suggestions of aerial views of Zen gardens in his paintings. Also in the show was Genichiro Inokuma, a respected artist and teacher in Japan, who lived in New York from 1955 to 1975 making intricate abstract paintings.

Notable artists of Asian ancestry came to New York from Hawaii in the postwar years. Isami Doi spent important phases of his career in the metropolis in the 1920s and again in the 1950s. In the first instance he was a student, making delicate black-and-white prints and surrealist-influenced figural paintings. When he returned to New York, he painted broad, brightly colored, nature-based abstractions. Reuben Tam went from Hawaii to California in 1940 and then to New York. He exhibited his color-saturated paintings widely, being represented by Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery, where Kuniyoshi also showed. While quite abstract, his paintings at the same time evoke misty seascapes, which in Tam’s case were often inspired by the ocean at Maui or at Monhegan Island in Maine. They suggest impressionism, the foggy vistas seen in Chinese landscape paintings, and the color-field experiments of Tam’s abstract expressionist contemporaries.

Alfonso Ossorio was in the thick of the abstract expressionist milieu, as he lived in East Hampton and was a friend and early collector of Jackson Pollock. Ossorio was born in the Philippines. Typical of that ethnically diverse country, his father was Spanish, while his mother was part Spanish, part Filipina, and part Chinese. Although he left the Philippines when he was eight, he returned in 1950 for a lengthy stay to paint a large mural on his family’s sugar plantation. At the time he wrote a poem that expressed his anxieties about his mixed ethnic background and possibly also referred to his struggle with his sexual identity:

The necessity of being

an Eurasian, deracinated

never at home in any

conventional category…

After its debut in 1954, the Mi Chou Gallery – created by people of Chinese ancestry and exhibiting mainly contemporary Chinese and Chinese American artists – was active for fifteen years in Manhattan; it has been called “the first Chinese American art gallery.” Artists who exhibited there included Gary Woo, Katherine Choy, Chang Shu-chi, and Walasse Ting. Yayoi Kusama, an esteemed artist today, spent a crucial part of her early career (1958-1973) in New York, developing innovative performances and obsessively intricate abstract paintings before returning to her native Japan. Her career announces a new ear in which more possibilities exist for Asian American women artists to achieve prominence than in former years. Nam June Paik was born in Korea and spent part of his youth in Tokyo, studied in Germany, and first visited New York in 1964. Paik, with is absurdist performances, was a central member of the international Fluxus movement, and he became a major pioneer of video art. In the 1970s he was increasingly drawn to New York, where he eventually made his home. The freedom of movement around the globe that he enjoyed has become normal for many recent artists. Similarly, On Kawara, who left Japan in 1959 after starting his career as a painter there, settled in New York but constantly travels worldwide. He is best known for his modest-sized, conceptual paintings of dates – the image on each canvas is the date of the painting. Kawara renders the date in the conventional manner of the country he is in at the time of making the painting – May 21, 1970, in New York would be 21 May, 1970 if painted in Paris – as witness to his cosmopolitanism.

In recent years an art history of Asian American artists has begun to emerge. Jeffrey Wechsler’s 1997 exhibition at Rutgers University, Asian Traditions/Modern Expressions, which traveled to Japan, presented fifty-eight painters and sculptors, from Korean and Hawaiian backgrounds as well as Chinese and Japanese, who worked in abstract styles in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s. The catalog of this exhibition is a pioneering investigation of the activities of Asian American artists in the United States in postwar years and opens up a new area for scholarly art historical research.

As international communications and transportation have become more rapid, Asian artists exhibit their work in New York with great frequency, and increasing numbers follow Noguchi’s example of having studios in both New York and Asia. Additionally, opportunities for artists of Asian ancestry born in the United States continue to expand. The situation has greatly changed from the one that Asian American artists in New York faced in the first half of the twentieth century. This investigation is the tip of the iceberg, to use an American expression, or like a rock in a Zen garden that suggests it is the peak of an immense mountain that lies below.

Tom Wolf is Professor of Art History, Bard College, NY. An artist, he has had paintings exhibited at Artists Space, New York; Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art; Koslow Gallery, Los Angeles and Art Gallery of Western Australia. He is a recipient of Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship, and Winterthur Museum and Library Fellowships.