Yun Gee

Yun Gee

New York City

Who was Yun Gee? A painter, musician, dancer, teacher, theorist, inventor, and more. A poor immigrant with a wealth of creative ideas. A solitary philosopher who actively promoted the arts. A dreamer whose personal vision and ambitions were thwarted by the political and social realities of his day.

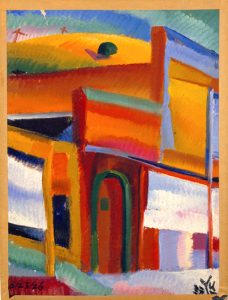

(San Francisco Street Scene)

(San Francisco Street Scene)

1926

oil on paper board

11 1/2 x 8 5/8 inches

A true modernist, Gee relished pictorial formal elements. Dazzling yellows and greens compete with sparkling reds in his San Francisco canvases. Even in the more limited palette of browns, dark greens, and ochres, the sparkling whites and crèmes activate his figures. Gee’s Paris portraits are equally rich but in a somber, more imperial manner befitting his illustrious sitters. A golden style seemingly blesses New York City’s energy and lethargy, its industry and humanity. The drawings and paintings reveal the power of his graphic line: the mystery of the dreamy symbolist dancer in slow moving, swooping curves, and the assertive hatchings to build up anatomical forms. Asian calligraphy informs much of his art, from the flowing, simple outlines of a Chinese landscape to the assertive diagonals of urban New York.

Historians debate whether Gee was first exposed to the liberating aesthetics of modernism in China under the New Cultural Movement as demonstrated by Gao Jianfu and his brother Gao Qifeng(1), active in Gee’s native province of Guangdong, or in the United States under the tutelage of San Francisco teacher Otis Oldfield. His source does not matter, for both Chinese New National Painting and American vanguard trends incorporated European avant-garde ideas. Gee’s art became an intense negotiation between Western modernism and Chinese tradition.

Yun Gee (standing, center) and the Chinese Revolutionary Artists Club

Yun Gee (standing, center) and the Chinese Revolutionary Artists Club

San Francisco

Gee understood that art was a manifestation of culture and a signifier of a nation’s identity. He believed incorporating some elements of Western art insured the creation of an advanced Chinese painting appropriate for the twentieth century, one that international art circles would applaud. He thought such a development would assist the world in recognizing the importance of the recently established, sovereign Chinese Republic. Such ideas derived from his early association with the nationalist cause of Sun Yat-sen. The Kuomintang, Sun’s political party, had its strongest power base in Gee’s native province and was also a crucial factor in the life of San Francisco‘s Chinatown, where Gee settled upon immigration to the United States. It was in that city in 1926 that Gee organized the Chinese Revolutionary Artists Club. He knew it would not be easy to transform Chinese painting, but his youthful fervor rationalized, “Since the republic is young and art is long, time will be an ally in the successful development of the new style.”(2)

Gee experienced remarkable success in San Francisco and Paris, but only a modicum of attention in New York City. In each of these places, even the supposedly liberal French capital, racism prevailed and ultimately determined Gee’s fate. Working within small art circles and with only a limited support system, Gee remained an outsider, a Chinese émigré, never fully accepted by the white-establishment. He was ignored long before his death in 1963.

Gee’s posthumous reputation began in 1968 when New York dealer Robert Schoelkopf gave him a solo display. Six years later, historian Diane Cochrane contributed an article on him for American Artist. She identified Gee with Synchromism, the international color abstraction movement that Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Morgan Russell invented in Europe and introduced to the United States. It was Gee’s amazingly sophisticated and innovative early work as a color abstractionist that inspired subsequent interest. In 1979 the William Benton Museum of Art organized the first retrospective devoted to the artist’s entire career. Since then Gee has been repeatedly “rediscovered” and “reclaimed” in numerous newspaper and magazine articles, books, and catalogues. Despite this quarter of a century of attention, the name of Yun Gee stirs little recognition in the minds of most art lovers. Why?

The simplicity of this question betrays the complexity of its answer. People consider history as the straightforward record keeping of events as they really happened. But history books are actually fictitious narratives. As theorist Donald Preziosi explained, writing about art is “a uniquely powerful medium for fabricating, sustaining, and transforming the identity and history of individuals and nations.”(3) Writing about the past is as much an act of creation as is the painting of a canvas. From the vast array of artists active during a certain era, authors select only a few, whom they rank as great, to demonstrate their interpretation of a particular movement. Preziosi concluded that “the principal product of [writing] art history has . . . been modernity itself.”(4) The concept of “the modern” as it applies to painting dates from the nineteenth century and has been identified first and foremost with Frenchmen such as Monet, Cézanne, Picasso, and Matisse. Historians constantly retell the biographies of these masters and repeatedly praise their art, while remaining silent about most other painters.

Modernists in France reacted against established customs to create a new art that was more in accord with their contemporary circumstances. Progressive trends continued to dominate through the first half of the twentieth century, expanding geographically in Europe beyond the borders of France to the United States and elsewhere. Originating in nations with strong imperialist ambitions, modern art became a crucial export in the colonizing process, demonstrating alongside technology the superiority of all things Western. The construct Modernism = Western culture = White was implied in the early histories. In these books Gee had no place, just as during his life he remained an alien.

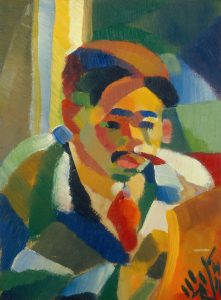

Untitled (Self-Portrait)

Untitled (Self-Portrait)

1926-27

oil on paper board

9 1/8 x 7 inches

It was only in the 1990s that postmodernist methodology solidified Gee’s reputation. Postmodernism marked a radical break with the modernist belief that art should be devoid of any content outside the object itself. Dissatisfied with established assumptions based on a male-dominated, white and Western hierarchy of domination, historians adopted broader and more varied intellectual approaches in accord with the ever-increasing diversity and globalization of the world’s artists and audiences. Issues such as race, Orientalism(5), and reception (both patronage and criticism) became popular avenues of investigation.

American art historians began studying artists marginalized due to their race, religion, ethnicity or other factors. By doing so they expanded the canon of American art, creating a more accurate, inclusive and truly national history. The recent English-language publications that reference Gee or focus solely on him have such postmodernist agendas. The artist has become a star in studies on Asian American art as well in regionalist histories focused on West Coast modernism. Just two years ago, scholar Anthony W. Lee, the leading authority on the artist, edited a monograph about Gee’s art, poetry, and writings.

And for the first time, Gee’s reputation blossomed in Asia. With the advent of a truly global art scene, that continent finally accepted its own modernist heritage. In 1992 the Taipei Fine Arts Museum celebrated Gee’s art with a major retrospective and sizable catalogue. In 1999, the first biography on the artist was published in Chinese. That same year works from Gee’s ex-wife’s collection brought soaring prices at a Taipei auction.

In this twenty-first century world without aesthetic borders, Yun Gee has at last been granted his place in the history of modern art.

Ilene Susan Fort is The Gail and John Liebes Curator of American Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

1. Gao Jifeng (1879-1951), founder of the Lingnan School and his brother Gao Qifeng (1889-1933) were both enthusiastic promoters of the Xin Guohua painting, literally: New National Painting (new ink painting), emphasizing national character & modernity.

2. Yun Gee, “Art in the Chinese Republic,” late 1920s, unpublished manuscript, quoted in Anthony W. Lee, Picturing Chinatown: Art and Orientalism in San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), p. 218.

3. Donald Preziosi, ed, The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology. Oxford History of Art series (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 18.

5. Orientalism was a term invented in the late eighteenth century by Westerners to signify their superiority and political dominance of non-white Arab and Asian peoples.

•BACK•