Revolutionary Artists

By Anthony W. Lee

Excerpt from the book Picturing Chinatown – Art and Orientalism in San Francisco

We know very few details about a remarkable artists’ collective in 1920s Chinatown, the ambitiously named Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club. It has left little trace, though some important facts remain. The club was formed during an intensely anti-Chinese moment in San Francisco – just two years after the passage of the 1924 Immigration Act, the harshest legislation yet passed to exclude the Chinese from the United States. The club was devoted to “doing [modernist oil] work that is essentially Chinese,” the San Francisco painter Otis Oldfield once tried to explain. Its studio was located in a small, cramped room at 150 Wetmore Place, on the western fringe of Chinatown. All its initial members were young Chinese immigrant men, most of whom had been working in oils for only a few years. They apparently took each other, Chinatown’s streets, its population, and several selected studio props – mostly objects from Chinatown’s stores – as their primary subjects. They were led by a charismatic immigrant named Yun Gee, who had arrived in San Francisco in 1921 and was probably the only member of the group to possess American citizenship. Although easily the most accomplished and experienced painter among them, Gee was only twenty years old when the club was founded.

What was perhaps the club’s most important public event – certainly the one for which it is best remembered – took place in late 1930 or early 1931, when it hosted a much anticipated reception for the great Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. Rivera visited the city to work on what became two of his most celebrated American murals, Allegory of California, at the Pacific Stock Exchange Lunch Club, and The Making of a Fresco, Showing the Building of a City, at what is now the San Francisco Art Institute. Once in the city, he quickly drew the attention both of high-society San Francisco and of a small yet intense subculture of radical-political artists, and he spent most of his time shuttling back and forth between the scaffolds and the two groups of admirers. But he accepted the young men’s invitation to visit their studio and take a drink with them. Surviving accounts suggest that the reception for Rivera at 150 Wetmore Place ended up being quite inclusive; the club members were considerably outnumbered by the muralist’s upper-crust traveling entourage. The event must have bordered on the sadly-comic: San Francisco’s cultured elite, probably including many supporters of the Immigration Act, crowded into a small, upstairs room in Chinatown, where they quickly consumed the food and drink; the young men who were trying to pay homage to Rivera, perhaps trying to learn a few lessons on the easel from him, found their reception overrun by people they did not know; faced with few chairs, the party spilled out into the hallway usually frequented by Chinatown’s poor. Not only was the large Rivera physically uncomfortable on the club’s tiny, square, lacquered stools (“he overflowed on all sides,” a guest happily reported, which “must have cut him in two”), but he was also unable to communicate directly with most of his young hosts, since they spoke no Spanish, French, or Russian, the languages he knew. To compensate, Rivera is said to have lectured with exaggerated gestures; he spoke sometimes in Spanish, sometimes in French, hoping that a familiar word or two would find a comprehending ear. He apparently listened patiently and graciously to the members’ questions, whether he understood them or not. And he concluded by delivering a lengthy, convoluted pronouncement, a was his occasional wont, on the artistic and political implications of a mural practice, though none of the young men was likely to undertake anything so artistically ambitious.

It is unclear how Rivera’s grand visit affected the club’s members, if it did (they certainly hosted no other events of similar magnitude); but it is a fact that soon after, they admitted their first and only female member, Evan Chan… Their efforts at a new inclusiveness won the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club a brief write-up in the San Francisco Examiner, which praised the “boys” for their “bravery.” The writer was probably referring as well to the painter’s new manifesto proclaiming their determination to establish a “Chinese academy of art, where [we] can spread [our] theories of art to all Chinese students.” But their new resolve to reach out to Chinatown’s other youth – an ambition perhaps nurtured by the socially minded Rivera, himself a recent member of Mexico’s San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts – apparently came to naught. The club disbanded only a few years later, during the city’s most violent era of labor strife. In the late 1930s, some of its former members and fellow travelers continued to paint, to promote the work of Yun Gee (who had already left San Francisco), and to encourage the artistic efforts of an even younger generation of painters. By the early 1940s, however, the club was largely forgotten. Very little of its members’ work survives. As far as we know, the young men themselves held rare, irregular exhibits during the decade or so of the club’s existence, and only Yun Gee ever went on to show his work outside 150 Wetmore Place to any kind of wider critical acclaim.

The club members seem to have barely marked the larger artistic scene, either in the exhibits they staged, the works they left behind, or the direct, discernible influence they had on other painters. Indeed, in the years since its quiet dissolution, the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club has remained important only as a footnote to understanding the more famous Gee. Though even he usually merits only a passing reference in histories of Bay Area and California art, Gee can at least be identified against the backdrop of recognizable exhibitions and artistic movements. His more conventional career took him from the club to San Francisco’s mainstream galleries, and then to Paris’ famous salons, where, in the early 1930s, his work seemed to fit nicely with a general School of Paris style. He had his modest beginnings in a local, hardly note-worthy painting group, or so the histories go.

Yet we do a youthful Gee and the club’s other members an injustice if we cast them as simply another Saturday afternoon painting group . . . And we certainly read their ambitions too narrowly if we see them only in the context of the city’s regular mill of professional exhibitions and criticism. They did, after all, constitute a necessarily segregated painting collective and must have had some sense of the possibilities within their marginalized space – visions that may not have been captured in the institutional or critical categories developed by the city’s increasingly sophisticated network of dealers and critics, visions that were surely distinctive and fraught with contradiction during a moment of explicit antagonism against Chinatown’s inhabitants.

This chapter tries to reconstruct the early ambitions of the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club, especially the efforts of Yun Gee. It takes “revolutionary” seriously and argues that the term took into account not only the club’s artistic precociousness – its turn to cubist-derived experimentation when most of San Francisco’s art world was still preoccupied with more conservative styles – but also its political beliefs and affiliations. Furthermore, it describes Yun Gee’s effort to link the two spheres, modernist art and revolutionary politics, suggesting both the historical basis for that effort and the immense difficulties involved in maintaining it.

I begin by retracing the footsteps of Yun Gee himself, from his birthplace in Guangdong and the political and cultural developments of his youth in the new Chinese republic, to his experiences as an immigrant in San Francisco, and finally to his introduction to and quick embrace of Parisian painting styles. That narrative will help us make sense of the work done inside 150 Wetmore Place and the meanings behind his revolutionary paintings of Chinatown.

REPUBLICAN VISIONS

We know very little about Yun Gee’s education in Guangdong, but there are slivers of evidence to suggest that he was very much a product of the New Culture Movement, reflecting its urbane sophistication and showing an early interest in the theories of the radical left. He very likely trained as a painter in the studio of the famous Gao brothers, Jianfu and Qifeng – politicized Guandong artists who, among their many radical exploits, used a painting store as a front for a bomb factory for Sun’s Tongmenghui. Gao Jianfu held official military posts during the revolution and in 1911 was briefly military governor of Guangdong. After the failure of Sun’s provisional government, he and his brother retreated to their home and pursued painting as full-time careers, attempting all the while, like Sun, to reestablish a regional base for another Nationalist uprising.

In the late 1910s, when Yun Gee was a young art student, the Gao brothers proclaimed a new school, appropriately named the New National Painting, to readdress and reexpress revolutionary and nationalistic goals in art. Most of the developments in the new studio reflected their search for an iconography appropriate to the stalled republic. The historian Ralph Croizier notes the studio’s sustained interest in portraying the lion (a symbol of the awakened, untamed revolutionary urge – Gee would later call such imagery the “newly awakened spirit”), though many of the painters had not previously used any kind of animal imagery. It was a subject to which Yun Gee would return during important moments in his own career. Other works included decidedly Kuomintang content, as in images of railroads and factories (such as Sun had dreamed of building). Furthermore, the New National Paintings accommodated modernist ideas (imported through Japan) about style and technique; these included the dramatic atmospheric effects established by late nineteenth-century French landscape painting, the streaky, thickly loaded brush of impressionist paintings, the eccentric play with fixed perspective found in most Parisian work at the turn of the century, and more. While the artists borrowed these features, they did not simply imitate European art but rather put them into tense dialogue with more traditional elements in Chinese painting. In doing so, Gao Jianfu and his studio visually declared the presence and carefully managed the intrusion of Western thought in a Chinese republican art. They were, to borrow Crozier’s cogent summary, “smuggling” in foreign ideas, in part to vex “the traditionalistic polemicists and the patriotic art vandals.”

The New National Painting’s relationship to the radical left is less direct. The evidence suggests that the Gao brothers generally held to Sun’s more cautious and pragmatic approach to the Russian alliance. Gao Jianfu did, after all, become a professor at Sun Yat-sen University and the National Central University in the 1930s, two Nationalist (not Communist) institutions. But Sun called on their close colleague, Chen Shuren, to oversee the reorganization of the Kuomintang during its historic alliance with the Soviet Union, when it admitted the Chinese Communist Party. And in places, the Gao brothers’ theories about New National Painting echo the enthusiasm for vanguard proletarian theory found among members of the May Fourth Movement, as if they, like many others in the Warlord Period, were feeling their way toward a new revolutionary stance that would require new attitudes toward the masses. “All art not compatible with the masses’ demands definitely must fall into decay,” Gao Jianfu declared in a lecture at the National Central University. “It first must have lively truth adequate to move a general audience’s hearts, minds and spirit. In other words this is called ‘popularization.’” Gao’s use of the term “popularization” – which refers to an aristocratic art and privileges the vernacular even as it is directed at members of the elite university and urban masses who were his actual audience – suggests that he had some kind of truck with the most radical proponents of New Culture critique.

The Gao brothers, Chen Shuren, their colleagues, and their students had ample opportunity to explore the potential of the New National Painting. Throughout the Warlord Period, they undertook commissions to promote the cult of Sun and expand on his republican ideas. In 1926 they were named the official painters for the Sun Yatsen Memorial Hall, thereby becoming among the most important early caretakers of his apotheosis. In keeping with Gao Jianfu’s call for popularization, the studios organized public exhibitions, including the Guangdong Provincial Art Exhibition in 1920, which was one of the first government-sponsored art exhibitions in China. The event took place less than a year before Yun Gee set sail for San Francisco and may well have helped shape his sense of how artists’ collective should address its community. But there is, unfortunately, no evidence that he or his paintings were at the show. And so we can do no more than imagine him there, perhaps standing beside his old teachers, perhaps displaying his own early examples of New National Painting – and perhaps looking toward San Francisco as the next venue in which he could experiment with a visual language that suited a growing commitment to revitalize the Nationalistic cause.

NATIONALISM AND EXCLUSION

Yun Gee’s father was a paper son. That is, he gained his right to claim citizenship and enter the United States under a false claim, and he passed that right on to his son. Most working-class Chinese men who immigrated to San Francisco in the 1910s came under similar pretenses. Their numbers, though small compared to the huge influx of workers in the 1850s and 1860s, were nonetheless significant. The historian Ronald Takaki estimates that every immigrant who claimed legal status to enter the country in the era of paper sons could have been a child of a San Francisco Chinese only if each Chinese woman living in the city at the time of the earthquake had borne eight hundred children. The swell of Chinese arriving by boat, despite the exclusion laws still in effect, caused non-Chinese San Francisco no end of concern. Beginning in 1910, the government opened an Ellis Island-style processing center on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay; officials interrogated each Chinese arriving by boat in an attempt to separate legal from illegal immigrants. The arrivals were detained long and interrogated relentlessly; and the experience often bred intense rancor toward non-Chinese authorities. (As one immigrant wrote in a poem on the wall of an Angel Island prison cell, “Leaving behind my writing brush and / removing my sword, I came to America. / Who was to know two streams of tears would / flow upon arriving here? / If there comes a day when I will have / attained my ambition and become / successful, / I will certainly behead the barbarians and / spare not a single blade of grass.”) Even in the transcripts of Yun Gee’s interrogation, one senses a barely contained hostility between interviewer and immigrant. “What kind of an artist do you claim to be?” the immigration officer asked, as if he found the claim difficult to accept (perhaps the official had been numbed, or made cynical, by the outrageous claims made by the hordes of Guangdong peasants coming off the planks; how many “professionals,” “artists,” and “students” could there possibly be?). “Oil painter,” Gee replied simply and perhaps flippantly.

…

The increasing suppression of Chinatown provides an important backdrop for understanding Yun Gee’s experiences in his new home, especially his attempt to found a revolutionary artists’ club in the mold of the Gao brothers’ New National Painting studios. I will try to recover something of the earnestness but also the near absurdity of that goal – to organize an artists’ group intended to promote a republican state founded on egalitarian principles on the other side of the Pacific when he himself, like most working-class Chinese in Chinatown, enjoyed few political and legal rights. Indeed, the very terms under which he entered the city were in the process of being outlawed. Furthermore, the appeals to embrace Western thought and progressive thinking, issued by the leaders of the May Fourth Movement and their sympathizers, were generally ignored by white San Franciscans, who preferred to view the Chinese as unable to Westernize.

When Yun Gee arrived in San Francisco in 1921, Chinatown had already become an important base for the embattled Kuomintang, and those associated with the Gao studios seem to have played an instrumental role in that development. Under orders from Sun, Chen Shuren had traveled to the city to help raise funds for another protracted military struggle in China and to agitate for the cause as North American editor of the party’s New Republic Newspaper. There is no evidence that Yun Gee was directly involved in these party affairs, but he very likely found his way through Chinatown’s social and political labyrinths by observing Chen Shuren’s lead and taking advantage of the extend Gao studio network of immigrants. He later claimed that he had “entrée to the very center of activity in Dr. Sun’s quarters,” making his affiliation though not his exact role in reestablishing the Kuomintang.

At the time of his arrival the Kuomintang cell, whipped into nationalistic fervor, was remarkably active. Its members had disrupted the plans of the Chinese merchants (the Six Companies) to form an alliance with the Yuan warlord government, and they were ceaseless in their effort to preserve the quarter as a republican domain. They attempted to build a Nationalist air force; and however absurd the ambition may have been (“national salvation through aviation,” the slogan went), they actually succeeded in purchasing a few planes, training a few pilots, and even sending them to Guangdong to enlist Sun’s military. Gee also found a Kuomingtang faction increasingly interested in Leninist ideas. This interest can be attributed in part to the increasing leftward drift of the New Culture leadership, in part to Sun’s own concerns for party rigor, and in part to Chen Shuren’s position. But local forces were also at work. The political imagination of Chinatown’s revolutionaries was shaped by Chinatown’s own demographics, which made desirable a theory of revolution that did not require a mass industrialized base. Indeed, Chinatown’s working classes were largely unskilled, still trapped in the restaurant, laundry, and tourist trades. Moreover, at the height of the early Kuomingtang drive in the United States in 1925, the party could claim only about twenty-five hundred members in the entire country. The rest of the Chinese population, in San Francisco at least, was split among the conservative Six Companies’ waffling allegiances; the ambitions of the so-called Xianhengdang (Chinese Constitutionalist Party, successor to the old Baohunghui), which tried to link itself to the warlord regimes; or the simply unaligned. The San Francisco Kuomingtang was, by necessity, a vanguard party and could readily – almost too easily – draw on Leninism to imagine its relation to revolution. Its left leanings were further confirmed by Sun Yatsen’s alliance with Russia in 1924.

Where should we place Yun Gee on this political spectrum, and how did he envision his Revolutionary Club functioning within it? The clues, once again, are scant and mostly circumstantial, such as his early friendship with the writer and poet Kenneth Rexroth, at that time still an ardent Communist Party organizer, or with the painter Victor Arnautoff, a recent immigrant and hard-core Bolshevik, or his later contributions to an art exhibit at New York’s John Reed Club. These all point to Gee’s paying attention to the most active pro-Communist people and organizations in the cultural sphere, and they provide an image of a young painter, like so many other politicized artists in the city, grappling with the problem of transforming art into an activist medium. “We must make art become [a] real value and to be in step with Dr. Sun’s Three Principles,” he would soon write, without referring explicitly to the bias of his new artist friends toward the Communist Party. “Is this not what Dr. Sun said, ‘To save the world with art?’”

We also possess an early and remarkable unpublished essay by Yun Gee himself called “Art in the Chinese Republic,” with which to sketch a more concrete answer about the function of his club. It’s aim, he wrote, “is not to cultivate merely an art of compromise, nor a safe middle-of-the-road art, but to create an art that is vital and alive that will contribute to the development of Chinese painting technique. This is no easy task. But since the republic is young and art is long, time will be an ally in the successful development of the new style.” The “republic is young,” he explains, and his buoyant attitude is revealing. Yun Gee probably wrote this in the late 1920s, at a time when the Nationalist effort had taken a turn for the better. The great Northern Expedition – the military march from Guangdong to the northern provinces to engage the warlord regime – had just commenced and, with considerable help from the Chinese Communist Party, the Chinese in villages along the route were being organized and politicized. It quickly led to the overthrow of military dictatorship, and in 1928 a Nationalist government was established once more. The republic seemed to be reborn after nearly fifteen years of military rule, given added support and new life by elements from the radical left. (The marriage would be short-lived, however. In 1927, even before the formal reunification of the country was complete, Chiang Kaishek, Sun’s successor and the leader of the Northern Expedition, began to execute Chinese Communists and purge the Kuomintang of CP sympathizers.)

I believe that when he founded the Revolutionary Artist’s Club, Yun Gee was beginning to see it as a potential ally of the CP and thought optimistically of a nationalist regime that would incorporate theories and organizational skills from the Soviet Union. He was not a doctrinaire Marxist and never joined the CP despite the hankering of his friends Rexroth and Arnautoff; and the club under his leadership never formally affiliated with any of Chinatown’s openly leftist groups. But he, like many other young nationalists, recognized how the Kuomintang benefited when it admitted CP members and put its own political philosophy into dialogue with Marxism-Lenism. A tentative, anxious, but thrilling optimism, born out of partial embrace of the theories and practices of the Bolshevik Revolution – that must have been the tone underwriting the young men’s collaboration to found a new revolutionary club.

Head of Woman with Necklace ~ 1926

Between 1925 and 1927, Yun Gee took classes at the California School of Fine Arts. There, under the tutelage of Otis Oldfield, he continued the experiments with French-derived styles that he had begun in the Gao school. Oldfield was himself a Parisian-trained painter, whose bright palette and thick, rhythmic brushwork had an impact on Gee’s developing technique, and we can immediately identify his effect on Gee’s early oils, such as Head of a Woman with Necklace. The face is made up of broad facets of color, all hinged together by the abrupt contrasts of a creamy ochre and a ruddy brown. The mouth is defined by a quick dash of an aqua blue on the left, abutted by a lighter, streakier blue on the right. There is a touch of Picasso’s early cubism in Gee’s handling of the nose – a flat, thick, vertical stroke that alternately stands for bridge and shadow – and something vaguely Cézanne-like in the transitions between the different shades of ruddy brown on the cheek and in the hollow around the mouth. We see a bit of Henri Le Fauconnier in the big blue almond-shaped eyes, particularly in how they sag and extend outside the contours of the cheeks. And there is everywhere Oldfield’s own peculiar overlap of hot and cold colors, what he famously called “Color Zones.” Or take the early Landscape with Telephone Poles. It smacks of a confrontation with Cézanne’s 1880s landscapes with its fussy blocky sky, its cantilevered arrangement of vertical streaks, and its patches of barren canvas. The whole central section – the odd lining up of edges into a single crease to give the impression of a downward flow, the alternating thick and thin application of paint – is indebted to any number of paintings from the Mont Sainte-Victoire series (I think particularly of the 1886-87 Mont Saintre-Vitoire with Large Pine in the Phillips Collection). Or take Gee’s portrait of Oldfield himself. The more congested arrangement of facets suggests an engagement with the canvas of Robert Delauanay and Sonia Delaunay-Terk, André Lhote, Amédée Ozenfant, or perhaps even Roger de La Fresnaye. Compared with Head of Woman with Necklace of just a year earlier, the Portrait of Otis Oldfield is tighter and more overtly constructed. The hot and cold color contrasts proliferate throughout the composition, turning the surface into a brittle but also interlocked membrane. The lower right part of the face – Oldfield’s left jowl – is a marvelous passage, where three trapezoidal forms (the lower lobe of his ear, the rise of his neck, and the negative space between the two) meet at a point on Oldfield’s jaw-line. They pivot around a hard edge and, as they almost become detached from the task of description, pull the dark green block of Oldfield’s lower face with them. That block seems to hover half of his jaw. It becomes a detail – a self-contained form – independent of the rest of the picture. (How could Gee’s friends not think of similar passages of hovering colored blocks in paintings by de La Fresnaye?)

(Landscape with Telephone Poles) ~ 1926

These paintings suggest the quickness and ease with which Gee digested the examples put before him, and their changes in style argue for his vast appetite for new ways to attack the canvas and his willingness to experiment. They do not simple borrow features from the salon cubists and elaborate on them within the format of classical Chinese painting, as the Gao studio once advocated, but are instead a more direct confrontation with Parisian styles, immersed more fully in the logic of cubist and post cubist painting. The experiments with the new vocabulary must have been exhilarating, and Yun Gee described them in his later writings with obvious relish and sometimes melodrama: “I, Yun Gee, ask for the freedom of my art,” he would later imagine himself declaiming during this moment. “I wish to speak to the spirits of the great new masters . . . I wish to forget the merely academic . . . I wish to go to the new from the old even as my forebears went to the clean from the unclean . . . The old is dead, and only the dead can tolerate it. Lead me to the future.” Or in another recollection, he likened the experiments to finding the roots of an awakened sensibility: “This medium [i.e., oil], with its everlasting qualities, has the possibility of giving a new art a new snap, helping it to retain all its racial character, if not its primitive force.” The new paintings did not constitute, as he declared in the manifesto, “a safe middle-of-the-road art” but attempted to be alive to the most vital modernist forms available.

In their radical embrace of modernist forms, the paintings adhere even more fundamentally to the calls of the May Fourth leaders, who wanted no truck with any lingering forms of a classical culture and demanded instead a clean slate on which to write a new nationalist narrative. Gee even dated most of his paintings to the year of the Republic of China’s first founding in 1911 (thus writing “16” instead of “1927”). Furthermore, the paintings are not easily characterized by any single line of development; Gee appears to be pushing forward to explore a broad range of possibilities (his self-conscious and experimented “development of Chinese painting technique”), as if the revolutionary energy were voracious.

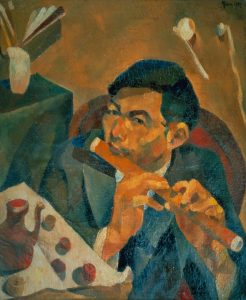

The Flute Player ~ 1928

The disparity between means and ends – between the small oil on paperboards and a larger nationalist dream – must not prevent us from seeing either the seriousness or productiveness of the project. For the dream of a nation-state could transform all kinds of subjects into metaphors of health, well-being, fecundity, and rebirth. The delicate balancing of edge with edge and volume with volume in Gee’s famous self-portrait, The Flute Player (see plate 7), posits a pictorial relationship whose logic is not only compositionally but metaphorically driven. The teapot pours apples from its pout, bringing forth sweet, ripe fruit. The apple closes to the tip resembles it in shape and color; those dropping below have become more differentiated and are now ready for the taking. The womblike teapot provides sustenance to its beholder and to those who know how to take from it. The paintbrushes and fan in the upper left jut out from a porcelain vase, like flowers in a pot. The whole assembly is raised on a pedestal of green and, through the cast shadows of the fan, is given a weight and monumentality far in excess of its modest contents. And it is the painter himself who sits amid the objects from Chinatown’s stores, playing a song to their significance and allowing them to endow him with an artist’s identity as he transforms them into a nationalist poetics. The tilt and angle of his fingers match the wisp and bend of the teapot neck, each describing the other in a rhythm that exceeds the simply compositional.

Gee’s paintings between 1926 and 1927 were among the most adventuresome being done in San Francisco. Already in 1926, he was courted by a group of avant-garde artists, including Otis Oldfield, to collaborate in exhibiting their works. He was the only member of the Revolutionary Artists’ Club invited. Together, the avant-garde collective founded the Modern Gallery on Montgomery Street, just outside Chinatown (for the first time since William Clapp had taken the reins of the Oakland Art Gallery in 1918, a gallery was showing highly experimental work on a regular basis). In November 1926 the collective gave their first one-person exhibition to Gee. By most accounts, the show was a success, with most of its seventy-two paintings sold (admittedly a hyperbolic claim, both in the number of paintings hung and sold, and there is nothing to corroborate it). The show gave the young painter much more visibility among the city’s dealers and critics than he had ever enjoyed before, and he began to receive favorable newspaper reviews. (The acclaim was short-lived in San Francisco. By 1933 the critic from the Argus had had a change of mind, calling Gee’s paintings from the 1926 show “ultramodernistic, ultra-abstract and, in our opinion, ultra-terrible, artistically, from any point of view”). Gee’s growing reputation may have first brought the club to Rivera’s attention.

Those Bay Area art histories that actually mention Gee tend to see in the show at the Modern the rough beginnings of his rise as a conventional kind of modernist. They find supporting evidence in events both before and after the exhibition. In lat 1925 or early 1926, just before the founding of the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club, Gee burned all of his previous work – presumably, the paintings he had either brought from China or made in San Francisco in the style of the Gao studio, which he claimed totaled some two hundred works – in a celebrated bonfire. (There are no known photographs of the event, but I like to imagine it along the lines of the Chinatown Squad’s opium burning.) This was the sort of gesture one came to expect of an avant-garde artist, an identification he confirmed by joining the Modern just a few months later. After the show, he rehung the unsold paintings for the occasion of Oldfield’s wedding, whose ceremony and reception he orchestrated. Apparently, the event was a bohemian success. When asked if he minded that the paintings had slipped sideways because of all the thumping and dancing, Gee is said to have responded, in good modernist argot, “Oh, no, it just gives them movement!” Less than a year later, Gee left San Francisco for Paris, as if not only Chinatown but San Francisco itself were too limiting for such talent. There, he met Ambrose Vollard, André Lhote, and Gertrude Stein and became a friend of Prince and Princess Achille Murat, wealthy patrons of the newest Parisian style of painting. For a time he lived a bohemian life in the grand manner of a Montmartrois. He studied at the Luvre (every day, so he claimed) and after looking carefully at the work of Courbet, imagined himself as a similar kind of painter-rebel, complete with wispy goatee. In December 1927 he obtained a solo exhibition at the Galerie Carmine and in April of the following year, another at the Galerie des Artistes et Artisans. In 1929, he exhibited in that most hallowed of modernist venues, the Salon des Indépendants; later in the year he had yet another solo show, this time at the venerable Galerie Benheim-Jeune. From periphery to center, from club painter to modernist artist, from the ancient East to the modern West – so Gee’s career has usually been traced.

The conventional assessment is not entirely wrong. Clearly Paris held allure for the aspiring artist, as did the truculent Courbet, especially for a painter trained by the Francophile Oldfield. And Gee undoubtedly became more interested in aesthetic theories of the most intricate and esoteric kind (he soon developed a theory of “Diamondism,” a derivative of Orphism.) But the usual story makes of Gee’s career an unbroken sweep toward modernist glory, and it suggests that his reasons for leaving San Francisco’s Chinatown and the club he founded were purely artistic. I will only remind us of those brief moments of optimism, in the middle years of the 1920s, when the experiments in modernist styles seemed to Gee like a possible solution to the call for a New National Painting. But I also wish to suggest how, under the sign of anti-Chinese sentiment and the 1924 Immigration Act, they took him on a different course.

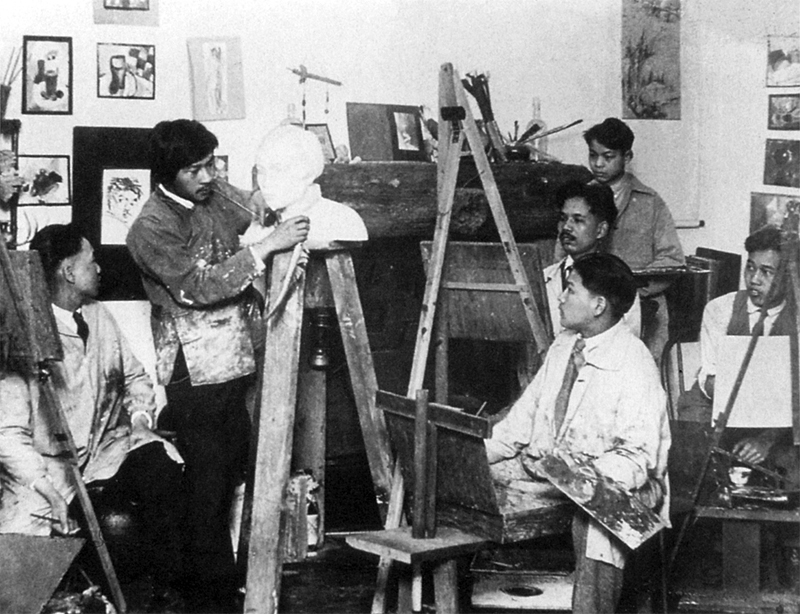

STUDIO AND STREET SCENES

Gee led a threadbare life in Chinatown. He had no steady job (and perhaps no work at all during his stay in San Francisco) and probably survived on the few dollars provided to him by his working father. The studio on Wetmore Place probably doubled as his bedroom, and he very likely shared a bathroom with a dozen families. Like most working-class Chinese, he rarely ventured outside Chinatown and relied on friends like Oldfield to escort him to art classes or even to the opening of his own show. Because he spoke English poorly (though he wrote it fairly well), few teachers at the School of Fine Arts wanted to work with him. Still, he probably had a better command of English than the other members of the Revolutionary Artists’ Club, who were mostly cooks and launderers in Chinatown’s back rooms. The other members remain largely unknown – there were probably a dozen at most – and perhaps were marginally better off than Gee, but they most likely had to pool their meager funds to buy and share precious art supplies. Gee himself painted primarily on paperboard, a much less expensive surface than primed canvas, and legend has it that for many years he used a laundry board as an easel. Given the group’s poverty, it is all the more remarkable that they gathered in such finery for a photograph, which, on closer inspection, has the look of being carefully staged to announce publicly the club’s existence. The suits, vests, and ties must have cost them a small fortune.

The Revolutionary Artists’ Club

I know of no other group photograph of artists in Chinatown from this time, and [the photograph above] may be the first of its kind. Only one other contemporary photograph displays the interior of a Chinatown studio, and the differences between the two are instructive. Whereas the old man in [the photograph below] is presented as if in a domestic space (the Victorian wallpaper, squat fireplace, and display of stringed instruments, precisely arranged, are all given careful attention), the Revolutionary Artists’ Club members choose to accentuate their studio as a working space. Whereas the artist-musician strums a tune for the benefit of his photographer in an ostensibly spontaneous performance, the club members prefer to ignore the camera and stage themselves attending instead to their leader, as if they are caught in the action of New National Painting. Whereas the paintings in [the image below] are arranged for the benefit of the viewer (the large landscape has been taken off its hook, set against a table – we glimpse the white tablecloth jutting out in front of his left knee – and angled to fit into the viewfinder), the club members prefer to hide their work behind the monochrome of wood panels. The comparison suggests that the photograph of the Revolutionary Artists’ Club is full of the painters’ self-consciousness, revealed in their strategic gestures and dress, careful orientation of bodies and easels, hidden paintings, and deliberate congestion. The members understood the importance of putting on a public face in non-Chinese San Francisco, registering their efforts as serious and determined, and presenting a formal collective identity – as if they had learned that painting for the revolution abroad still had a local significance and a local audience, some of whose members (the patrons of the Modern Gallery and other venues) cared little about New National Painting, only about identifiably modernist work.

The self-consciousness inscribed in the group photograph can also be discerned in Gee’s paintings of Chinatown’s streets, but the experience of living in a segregated, racist city could give that self-consciousness alternately brighter and darker aspects. When he painted the streets in a small oil on paperboard called San Francisco Chinatown, Gee found it best not to include any people on the sidewalks, as if the quarter was most amenable to being pictured when composed entirely of new street lamps (with bright rays jutting emphatically in all directions), tall building façades, broad roads, and sharply angled rooflines. Chinatown seemed most coherent and consistent as a brilliant spectacle, devoid of social relations and daily activity. Its identity was best understood as a carefully constructed place. A modernist, cubist-derived aesthetic lent itself to such an attitude, for it insisted on fitting together component parts into an overall set of surface relations. Brushes and strokes fell into jigsaw patterns, and the painter’s particular task was to provide a level of visual interest in the play of colored facets and edges. Look again at the painting’s middle-right side, where a red awning arches out over a bright sidewalk and reaches down toward a post (a lamppost? of the ubiquitous hexagonal style that Stellman and others observed?). That arcing creates a yawning space between awning and post that is playfully filled in with manic cream-colored and pink brushstrokes, seeming to extend the awning by giving it a ghostly (diluted) presence, beckoning it further out over the walk so that it droops down toward the post and caresses it, just barely. Or look at how the series of pitched roofs create a rhythm of their own, quite apart from the buildings they ostensibly top. The roofs form a gigantic, looping, sideways zigzag and only partially correspond to the solid buildings below. The more oblique bottom half of the zigzag to the right has the look of a halo; its lower right side flutters over a building corner and, with a messy bottom edge at right, seems to seep into the building’s side. Or consider the street lamps, whose jutting electric rays look more solid and rigid than any of the iron posts. The lamp at center-left has seen fit to obey an overall design logic, ordering its rays to cut short their reach so as to fit nicely into the building façade set aside for them. These are all playful, punning visual gestures. Paintings of Chinatown sometimes permitted this indulgence, as if New National Painting could risk the free play of a liberated sensibility and the streets of Chinatown enabled that exuberance.

At Chinatown’s outskirts, however, Gee’s attitudes toward the canvas changed. One painting, San Francisco Street Scene with Construction Workers, depicts a scene familiar to the San Francisco Chinese, the Stockton Street tunnel separating the city’s downtown from Chinatown proper. We see the cavernous mouth of the tunnel at the bottom center, just beyond the crest of a subtle rise that is the intersection of Stockton and Sacramento Streets. The location is significant because it is the very south-western edge of Chinatown, the extreme boundary of the policed quarter beyond which, through the tunnel, an entirely non-Chinese San Francisco begins. Gee places us inside the quarter; we look out, mindful of an invisible barrier, watching another city take shape over the tunnel on California Street and observing its activity from a necessary distance. The construction workers above are held on an impossibly precipitous slope, as if they are tacked onto the picture’s surface and absorbed into its fiction, as if they constitute an entirely separate tableau behind the foreground scene, beyond the quarter’s boundary. A street sign to the far right, barely legible as “Cali[fornia],” names the street above, where the workers stand, not the intersection in which we are placed. It thus holds particular metonymic value, acting as a link to the burgeoning space outside Chinatown’s closed borders and pointing toward the steep, disconnected space at the upper half. A stroller (a flâneur), deliberate in his step, makes his way past the sign on his way south toward the tunnel and an imaginary freedom – or at least one denied to most young Chinese of San Francisco. He sports a pipe and probably is a stand-in for the painter himself, who regularly was pictured with pipe in mouth. But it is a stroll that the young Gee was allowed to make only infrequently or with escort; there is pathos in the carefully measured step of the surrogate, who traverses a boundary that the painter could rarely cross. The whole scenario of flânerie must take place in the fantasy world of the painting.

Compared to San Francisco Chinatown, with its exuberance and punning, San Francisco Street Scene with Construction Workers is less clearly organized and less expertly executed. Indeed, to my eye, the painting is amazingly awkward for someone generally so accomplished before the easel. Its facets and edges have none of that tense, brittle stability Gee achieved in San Francisco Chinatown; its rectangular blocks have none of that fragile, hovering surface found in Portrait of Otis Oldfield. The upper sky, which is made up of Cézanne-like passages of edge-to-edge transitions in color, only hints at the tremulous, nervous delicacy usually found in Gee’s early landscapes. The painting is not really unified – or it is held together by its overall hue, an orange-yellow mixed into most of the pigments. Despite a more controlled palette, Gee seems unable to smooth over the intersection of Stockton and Sacramento Streets with his usual surface consistency. These differences, I believe, reflect less the constant experimentation in Gee’s working mode than the locations he was trying to picture. Or better, the experiments took on different aspects when the painter tackled such differently fraught subjects.

San Francisco Chinatown is a view inward. It is best understood as a self-sufficient image, positioning the painter himself on the streets only as a disembodied presence. Its composition aims at internal consistency with its deliberate and careful symmetry of vertical and horizontal elements and rhythm of overhead triangles, as if that kind of consistency and visual pleasure came from the place itself. Inside Chinatown, the streets and storefronts, it seems, presented a carefully arranged image the readily gave itself over to painting. At the quarter’s edge, however, the self-sufficiency of the spectacle broke down. Street Scene with Construction Workers is a view outward and thus suggests the pull of the tunnel, the distant vista, and the complex urban scene beyond Chinatown’s edge. But the painting manages that combination only uncomfortably and is interrupted by Gee’s own self-conscious desires. At Chinatown’s borders, he was most acutely aware of the meaning of his physical presence to the city outside – most aware of his difference in San Francisco – and this required that he encode that knowledge in the figure of his convulsed stroller and, indeed, in the painting’s awkward construction. On the one hand, Chinatown inspires fascination and self-reliance, the hopes for a new republic and a modern society; on the other, it gives rise to self-consciousness and loss. At one end of the quarter, the streets suggest Chinatown’s own fullness and offer the possibility of visual delight; at the other, they convey the quarter’s isolation and distance. At Chinatown’s heart, the brilliant corners and elegant lamps require no singular bodily awareness on the part of the observer but promise a collective fantasy of plenitude; at the edge, the fantasy disappears, and a simple comparison with the non-Chinese space above the Stockton Street tunnel makes necessary an imaginary surrogate to carry out the fiction.

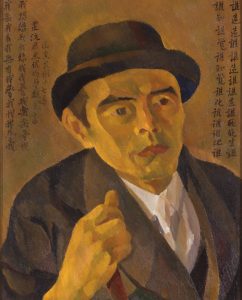

Chinese Man in Hat ~ 1928

The closest Gee came to combining these two attitudes in one painting was a small oil on paperboard, Chinese Man in Hat, probably a portrait of a Revolutionary Artists’ Club member. Running halfway down either side of the central figure is Chinese verse. On the left side, it reads:

I am thinking, thinking of me, I am thinking of me;

I am worried, I am happy, I am at once worried and happy;

I have nothing, I have something, I have at once nothing and something;

I am dreaming of myself, I am dreaming of myself.

This set of contradictory states and the sitter’s desire to see himself at a hallucinatory distance are taken up in the verses on the right:

Who creates, creates whom, who creates whom;

Who is alive, who is dead, who is both dead and alive;

Who know, who is enlightened, who knows and is enlightened;

Who changes whom, who changes whom.

“I am thinking of me,” Gee writes on the left, and as if in response on the right, he asks, “Who creates whom.” The acts of thinking and painting hinge on each other, but they are riven with a deep anxiety. It causes the painter to imagine the sitter as split into two – the “I” on the left, focuses and possessive, who alternately has an does not have, who thinks and dreams of himself, who tries to believe he is happy; and the “Who” on the right, an exteriorized and disembodied self, who changes and creates (art? The republic?) but is dead as well as enlightened. The central figure points to himself, as if to lay claim to the contradictory set of characterizations. The pathos of the image lies in the belief that the painted subject will accommodate the competing selves within his body, somehow managing the potential for fragmentation. Unlike the paintings of Chinatown’s streets, where the painter’s inward or outward gaze could address the contradiction between a national art and the racist city in which it was created, the portrait’s of the club’s members had to locate and attempt to contain these competing forces in a single figure. Their bodies became ritualized spaces that displayed the antinomies of the club’s revolutionary ambitions.

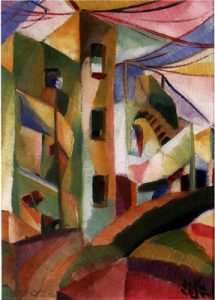

Houses on Hill ~ 1926

The argument of the paintings did not simply reside at the level of painted fiction but spilled over into Gee’s growing sense of himself on Chinatown’s streets. As the street paintings may suggest, Gee relished the sidewalks and storefronts and was sensitive to his experience of them. He frequently moved up and down the steep hills, trying to find a particularly sketchable subject. In Houses on Hill, for example, he painted the narrow façades and street lamps looming up over the arcing line of a sidewalk, stretching the windows and balconies higher and higher up the vertical of the canvas as he himself moved further and further downhill, thereby approximating his shifting physical relation to the buildings above. Like the many flâneurs before him, he walked with attentiveness and alertness, typically scouting for a useful street scene transform into subjects for the easel. What is especially significant on these strolls is that he apparently dressed for the part, too. As photographs tell us, he regularly donned the costume of the urbane stroller – fedora at fashionable angle, broad lapels pressed just so, a flowing tie knotted with the proper flourish, a walking cane with a nice, graspable hook – all these accessories for a man earning no income. It was as if he intended to masquerade as a privileged non-Chinese passing along the length of Grant Avenue, as Genthe had once done along Dupont Street. One account suggests the absurd, overproduced manner of his make-believe. Out on a stroll with Oldfield, Gee “had fitted himself out to be a Chinese carbon copy [of his teacher]; he’d gotten a beret he had a suit made that was as close as it could be, identical to the one that Otis wore most of the time; he’d gotten a cane and pipe . . . The beret stuck up on top of that wiry Chinese hair; it wouldn’t fit down on his head at all. The one that he had bought had not had that little threat that comes out of the top, so he got a piece of yarn and sewed it on. He had to have everything exact.” It is an odd, comical picture, this. We can only imagine Gee twirling his cane, jauntily stepping past the tourist shops and beneath the colorful canopies, disguised as the Francophile Oldfield down to the added yarn. There is obvious pleasure in the masquerade, in wrapping his body within the fashions of an Other. But just as in the accounts of the Chinese produced by the Chinatown Squad and its adherents, the costume is ill-fitting and suspicious, seeming not to accord with an underlying life. Its vulgar explicitness makes it parodic or even self-parodic.

Gee’s self-consciousness as an inhabitant of Chinatown suggests to me his keen awareness of the unstable nature of the Revolutionary Club’s New National Painting. It is as if the experience of living in San Francisco – his initial imprisonment and interrogation on Angel Island, the daily harassment by non-Chinese, the public burnings and police raids, the never-ending struggle of Chinese men to find a decent meal in such a pinched economy, and, yes, even the violence between the tongs and political parties themselves – made clear the idealism beneath the Kuomintang faction’s most ardent wishes and suggested that the Leninist theories of vanguard radicalism they had so recently embraced paid too little attention to the hard lives of most Chinese. Put simply, the utopian vision of radicalized painters confronted the material bases of immigrant existence. Despite the presence of an occasional celebrity like Rivera, life at 150 Wetmore Place was probably no different from that on the rest of the streets.

I have already rehearsed most of what is known about Gee’s early career and his ambitions for the Revolutionary Artists’ Club. The single extant photograph of the club can tell us only slightly more. In contrast to his masquerade with fedora and cane on the streets, Gee chose to put on a distinctly Chinese smock to create the club’s public face, allowing the splatters of paint to coat but not strip away an outwardly racial identification. If the club was indeed “Chinese” and “Revolutionary,” he was going to determine what the combination of those terms meant, or at least how it ought to be photographed, in San Francisco. The experience of living in San Francisco taught him that a Chinese artists’ collective had to hold two broad cultures, the republican East and the modern West, in some kind of awkward, explicit, visible tension. Remove Gee and his cohorts, for example, and 150 Wetmore Place takes on a decidedly different appearance. Without them the “Chinese” quality of the club quickly fades. With the exceptions of a landscape painting in the back and a teacup on the easel at right, little seems to reside in the artworks or in the characteristic procedures of painting. The sketches and drawings on the walls are vaguely cubist in style and certainly Parisian in origin (the sketch of a vase and brushes on the far right looks like a preliminary for the still life that eventually found its way into The Flute Player, but on its own it bears no strong trace of belonging to New National Painting). Indeed, the still lifes of tumblers and fruit seem better suited to a studio in the Bateau-Lavoir than on in Chinatown – this, remember, when photographs of Parisian studios amply displayed a similar ambiance and provided a ready model. “Revolutionary,” the art on the walls seems to tell us, describes more properly certain stylistic affinities with the School of Paris than the shift – the slide – between ambitious art and politics that the club stood for. Only that white bust of a man, whose features on closer inspection are seen to be Yun Gee’s, may give away the studio’s regular inhabitants. But even this detail is not without ambiguity, for it represents the painter in the most realistic terms possible and does not seem to match any of the stylistic experiments on the walls. We cannot even tell if the sketches in the background belong to the club’s seated members, since the painted surface before each is turned strategically away from us; the one to the right that actually faces us is decidedly, declaratively, empty.

The photograph is indicative of the tension in the entire project of the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club, which attempted to balance its explicitly modernist ambitions for paintings, the republican visions those paintings were to encompass, and the unusually harsh life in Chinatown. Art and politics meet, the photograph seems to say, but is unclear how (under what set of terms, given the conditions in San Francisco) the meeting was or might be productive. This general tension and ambiguity, the pathos and reality of the members’ lives and the historicity of their efforts, are what we must firmly grasp if we are ever to understand the conflicted, anxious vision of an early Chinatown’s artists’ collective and its practice. In painting Chinatown’s sidewalks and buildings, its simple teapots and the small commodities sold in its tourist shops, and its people, the club’s members attempted to imagine an ideal model of nationalist artistic production to accompany a nationalism that had been rejuvenated in China itself. They developed their model in an increasingly hostile Western society that, in this early moment of early modernist art, still permitted those painters on the margins to express collective meanings in avant-garde works. That project in San Francisco ahs been all but erased, though in the previous pages I have tried to hint at its conflicts and complexity. Though the club’s vision now seems hopelessly utopian, it is still important to grab hold of, especially if we are ever to recover a culture of immense commitment that once existed in touristic Chinatown. Otherwise, we face its complete erasure. Otherwise, two cultures had met, a certain modernist cultural history happily exclaims when confronted with the photograph of the club, and it must have been a moment of charming innocence – before one culture completely absorbed the other.

Anthony W. Lee is an art historian, critic, curator, and photographer. As a critic and scholar, he writes about American photography and modernist painting in the period between 1860 and 1960. As a photographer, he documents ethnic and immigrant communities. Lee teaches a series of lecture courses on art since the French Revolution and seminars on photography before and after World War II. Many of his seminars have resulted in exhibitions curated by students.

Lee is the recipient of the Charles C. Eldredge Prize for Distinguished Scholarship in American Art, given by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American Art, and the Cultural Studies Book Prize, given by the Association of Asian American Studies. He is founder and editor of the acclaimed series Defining Moments in American Photography.

•BACK•