San Francisco, Paris, and New York: Works by Yun Gee from 1926 – 1933

by Robert E. Harrist, Jr.

Many decades before a current generation of young Chinese artists living in the United States achieved international recognition, Yun Gee (1906 – 1963), a restlessly inventive painter, sculptor, poet, and performer born in Guangdong province, held one-man shows in San Francisco, exhibited in Paris galleries, and gave classes in “New Cubism” in his Greenwich Village apartment – all before reaching the age of thirty. Although Yun Gee rarely exhibited during his later years, he is by no means forgotten, and growing interest in twentieth-century artists who bridged cultures and nationalities has focused new attention on his work. The present exhibition offers a good opportunity to study paintings, drawings, and works of sculpture from the most productive period of Yun Gee’s life. Between 1926 and 1933, Yun Gee explored a startling broad range of styles, reflecting his intense engagement with avant-garde art in the United States and Europe. The works in the exhibition, all of which focus on the human figure, also embody a confluence of artistic practices, which in some cases make explicit Yun Gee’s identity as a Chinese-born artist. The latest paintings in the exhibition, a set of three studies for his now lost Last Supper of 1933, reveal a different and quite surprising dimension of Yun Gee’s career – his investigation of the traditional iconography of Christian art.

The California Modernist

Yun Gee was born, as he liked to point out, on George Washington’s birthday, February 22nd, 1906, in Kaiping county of Guangdong province. His original name was Gee Wing Yun, which he transformed into the two-character name he used in the West, Yun Gee. He apparently studied traditional Chinese painting or guohua before leaving China in 1921 to join his father in San Francisco. No examples of Yun Gee’s guohua paintings in brush and ink have survived; any he might have brought to San Francisco with him or produced after he immigrated probably were among the paintings he burned in 1926 in a pyromaniac renunciation of his early work. Yun Gee once mentioned favorably the paintings of Gao Jianfu (1879 – 1951), who with his brother, Gao Qifeng (1889 – 1933) attempted to modernize Chinese painting by applying vaguely Westernized pictorial styles they learned in Japan to the representation of contemporary subject matter; the Gao brothers’ activities as revolutionaries also appear to have inspired Yun Gee. There is no documentation, however, that Yun Gee had any contact with these artists or their followers, who were teaching in Guangdong while he was a boy, and his surviving paintings display no traces of their style.

Of far greater importance to Yun Gee’s future as a painter than anything he might have encountered during his youth in Guandong – it is important to remember that he was only fifteen when he left China – were developments taking place in the San Francisco art world that made the city one of the most vital centers of American modernism outside New York. By the beginning of the Twentieth Century a school of California impressionism was well-established in the Bay Area, producing pleasant though intellectually undemanding images suffused by brilliant light and color. Against this local artistic background, the European modernist paintings shown in the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 were a revelation. Encompassing many of the works included in the New York Armory Show of 1913, the Exposition had an electrifying effect on local artists. In the words of the critic Willard Huntington Wright, by 1919 the San Francisco art scene was marked by curious transformations: “Sargent evolving into Matisse, Whistler fading out in Signac, Bougereau metamorphosing into Picasso.”

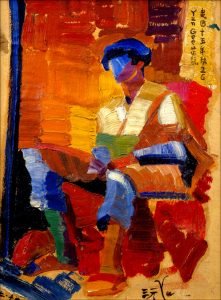

Man in a Red Chair

1926

oil on paper board

10 x 8 inches

An East Bay group known as the Society of Six, made up of self-consciously bohemian artists, produced rough-hewn interpretations of European modernist styles and began holding annual exhibitions that continued into the 1920s. During the same era, Modernism became entrenched at the California School of Fine Arts, where Yun Gee became a student in 1924. By far the most important member of the school’s faculty for Yun Gee was Otis Oldfield (1890-1969), who became the younger artist’s life long friend. Living and painting in Paris from 1911 to 1924, Oldfield had a superb knowledge of the various “isms” of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century art. As a teacher, Oldfield advocated a theory of “Color Zones” – his personal adaptation of the theories of Orphism and its American counterpart, Synchromism, founded by Morgan Russell and Stanton MacDonald-Wright. Oldfield required his students to paint in oil on paper, creating zones of color “methodically constructed in juxtaposition from the nucleus key-tone without preliminary sketch, and in pure color only.” Dated to the fall of 1926, Yun Gee’s Man in a Red Chair reflects Oldfield’s pedagogical method. The body of the seated figure emerges not from the presence of defining outlines but from the juxtapositions of roughly applied areas of color. Ocher, orange, and white in the upper body are set off by tones of red and orange that push the figure forward in space. Similar effects in the arrangement of colors in the legs, painted in orange, blue, black, green, and ocher, give the figure a compelling plasticity. Also essential to the building up of forms is the assertive directionality of the viscous brushstrokes. In Head of a Woman with Necklace, datable to 1926, the planes of color are broader and the paint thinner. Although this painting seems to be a product of Oldfield’s “Color Zones” theory, the huge eyes, starkly angular features, and intense colors strongly recall the work of Alexej Jawlensky, which Yun Gee almost certainly saw in an exhibition of the Blue Four-Feininger Jawlensky, Kandisnksy, and Klee – shown at the Oakland Gallery in 1925.

Drawings in the current exhibition from 1925 and 1926 show that Yun Gee had mastered a technique of rendering powerfully volumetric forms through the dramatic shading of faceted shapes derived from analytic Cubism. In figure paintings from 1926 – 1927, he created similar effects in a dazzling palette of intense colors Seated Man Reading depicts a massive figure, apparently a Chinese man, engrossed in perusing an open book. At the same time that the separated areas of color coalesce into shaded cubes and facets that seem strongly three-dimensional, they shift back and forth between appearing to be convex and concave surfaces, especially in the figure’s jacket and face. The cropping of the head and right shoe, as well as the massive proportions of the head and right hand, make the figure seem too large to be contained within the framed space of the picture.

Untitled (Seated Man Reading)

1927

oil on paper board

24 x 19 inches

It is hard to imagine a greater contrast than that between Yun Gee’s surviving paintings from his years in San Franciso and the traditions of Chinese guohua he had encountered as a Buddhist artist in China. In guohua, lines drawn with a flexible, pointed, animal hair brush define form; in Yun Gee’s paintings from 1926-1927, planes of color applied with a brush made of stiff, flat bristles build up pictorial shapes. Modulated, calligraphic outlines play almost no role in these paintings, nor do his later works reveal any greater sense of calligraphic line than can be seen in the works of artists with no connection to China. Yun Gee’s paintings also differ radically from those of Gao Jianfu and his followers. What those artists brought to Chinese painting was essentially an approach to modeling derived from Japanese interpretations of Western art. This is exactly the pictorial language that Yun Gee’s California paintings reject: planes of intense color, no gradations of light and shade, give paintings such as Seated Man Reading their volumetric presence.

The Languages of Yun Gee

It is not through their pictorial style or their subjects, which include Chinese figures and scenes of San Francisco’s Chinatown, that Yun Gee’s early paintings call attention to his Chinese origins; nor do his later paintings of Chinese subjects, such as Butterflies: Dream of Chuang-Tze, look even remotely like Chinese pictorial art. What does assert, powerfully and unmistakably, a connection between Yun Gee’s work and the art and culture of China is the presence of Chinese writing on many of his paintings and drawings. These inscriptions consist of Yun Gee’s signature, often combined with a date and sometimes a statement about where a work was made. In the upper right corner of Man in a Red Chair, the lines of writing include Yun Gee’s name in roman letters followed by the characters “Gee Yun,” a linguistic reversal of his name that he sometimes used. The second line reads, “Autumn of the fifteenth year of the Republic of China (Minguo shiwu nian qiu) 26.” This practice of dating works according to the Western calendar, indicated by the number “26,” in combination with the system of dating used in the Republic of China, which counted time from the year the republic was founded, reflects Yun Gee’s strong republican sentiments, explored recently in a study by Anthony W. Lee. The dual system of dating also hints that Yun Gee was living with two different concepts of time, one generated in China, the other in the West; one based on events in his homeland, the other prevailing in the United States, where Yun Gee actually made the painting. At the bottom of the painting is the artist’s signature consisting of the Chinese character “Yun” combined with the letters “Y-u-n” to form a bilingual monograph or cipher. Similar dates and signatures appear on several other paintings in the exhibition, and on drawings in the exhibition that also bear a seal stamped in purple ink with Yun Gee’s name in roman letters and in Chinese characters.

The longer inscriptions, especially those written as a block of text and placed conspicuously within a pictorial field, as in the Man in a Red Chair, Man Writing from 1927 and Chinese Man in Hat, painted in Paris in 1928, achieve the paradoxical effect of being both traditional and radically new. Since the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), Chinese painters had inscribed their works with passages of writing consisting of dedications, poems, or short essays. These inscriptions hover in an ambiguous space shared with the pictorial images, yet they belong to a completely different system of visual communication: while even the most rudimentary formats of Western art, most notably illuminated manuscripts, did integrate pictures and texts in complex visual patterns, the Chinese practice of writing on pictures has no true Western parallel, which would have taken the form, let us say, of Giotto or Rembrandt writing poems directly on the surfaces of their paintings. Considered art historically, Yun Gee’s inscriptions were alien to most Western viewers not because they were undecipherable but because they were writing, imported into a pictorial domain from which writing was normally excluded in the West.

At the same time that they establish continuity between his paintings and traditions of Chinese art, Yun Gee’s inscriptions can be interpreted as his adaptation of modernist experiments in combining words and images. The most familiar of these is the Cubist’s practice of inscribing words on their paintings-parts of newspaper mastheads or names that point to the subject of a painting, such as Picasso’s Ma Jolie (Museum of Modern Art) of 1911-1912, in which the title is written across the bottom of the canvas. In these Cubist works, the letters lie in the same two-dimensional plane as the canvas itself, but they also seem to hover in front of, or in some cases behind, the fragmented pictorial images. Although Yun Gee’s inscriptions, following Chinese conventions, are displaced to the sides of his paintings, rather than being written directly over the painted forms, they do establish a dynamic relationship between words and images, between the two-dimensional graphic space of writing and the fictive three-dimensional space of painting.

Yun Gee had second thoughts about several of his paintings that originally included inscriptions and painted them out in later reworkings. Photographs show that his Confucius of 1929 originally included a lengthy text carefully foreshortened to appear as if it were inscribed on a hanging scroll in the upper left of the sage’s study. Yun Gee replaced the inscription with a strange, giraffe-like creature intended to represent a qilin or unicorn, which was removed after the artist’s death. David The-yu Wang believes that Yun Gee’s decision to remove the inscription may have been determined by his desire to make his painting more acceptable to an American audience during a period when discrimination against Chinese immigrants was common: emblazoned with calligraphy, Wang suggests, the painting was too “Chinese” for Western tastes. It is just as likely, however, that Yun Gee came to see that in the relatively deep illusionistic space of the painting, words and images did not interact as successfully as in earlier works from his San Francisco years, in which the more abstract, two-dimensional picture surfaces readily accommodate the insistently flat medium of writing. Sensing that the tension between writing and painting was a distraction rather than a dynamic visual interplay, Yun Gee may have revised his work for artistic rather than economic or political reasons.

Self-Portraits: San Francisco and Paris

In spite of his imperfect spoken English, his lack of any reliable income, and the entrenched hostility toward Chinese from the larger community, Yun Gee flourished in San Francisco. In collaboration with Otis Oldfield, he founded an artist’s cooperative called the Modern Gallery on Montgomery Street, near Chinatown, and exhibited there in group shows. In November of 1926 Yun Gee had his first one-man show at the newly founded gallery, selling most of the seventy-two paintings he exhibited. Also in 1926, Yun Gee founded the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club, a group of young artists who received instructions from Yun Gee himself. During this same eventful year, Yun Gee met the French aristocrats and art patrons Prince and Princess Achille Murat, who visited his one-man show, bought two of his paintings, and encouraged Yun Gee to move to Paris. Scarcely a year later, Yun Gee had a one-man show at the Galerie Carmine in Paris, where he continued to exhibit regularly during the following two years and was introduced to writers, artists, and dealers in avant-garde circles, including Gertrude Stein and Ambrose Vollard, Picasso’s early dealer and friend. Yun Gee’s arrival in Paris was an artistic homecoming, to the fountainhead of the modernist styles that had inspired his brilliantly colored San Francisco paintings. But within a short time, his art underwent radical changes that can be traced in his self-portraits, culminating in How I Saw Myself in a Dream, datable to 1929.

By the time of his departure for Paris, Yun Gee had depicted his own features in several works. In an undated charcoal drawing, probably from his student days in San Francisco, the artist drew his sharp, striking cheekbones in long fluid lines, as calligraphic as any in his oeuvre, and rendered his features, eyebrows, and mustache in vigorous, angular strokes. His hair is an explosion of gestural marks that vividly record the motion of his hand and arm.

Yun Gee’s earliest known self-portrait in oil is part of a pictorially and symbolically complex canvas from 1926-27, Where Is My Mother. Yun Gee had not seen his mother since leaving China in 1921, and he probably knew they would never meet again. In a poem dated May 31, 1926, he wrote of the pain of being separated from her and of his fantasy of seeing his mother looking in on him while it was midnight in China but high noon in California. The final lines of the poem read:

I dreamed that I could bring her close,

Created the painter’s art

On the canvas

Mother looking out of the door,

By the mountain road a cart,

A plane in the air,

The ship of the sea,

Could I find my mother again?

In his painting, Yun Gee appears in the lower right. Pearl-like tears, defined by touches of white paint, stream down his cheeks. Set at a rakish angle on his head is a blue beret-headgear Yun Gee emulated Otis Oldfield in wearing. His arched eyebrows, drooping mustache, and goatee, painted in dots of purple and brown, are distinguishing features that recur in his later self-portraits. To the left and slightly behind Yun Gee is the head of a woman in a brown hat, tears falling from her eyes. This figure, depicted from a much lower vantage point that makes her seem to be peering down at something the viewer cannot see, is presumably Yun Gee’s mother, who he speaks of looking in on him in his poem. In the lower left of the painting is another man also wearing a brown hat whose identity is unclear. Behind the figures is a framed painting shown at a slight angle, clearly the canvas mentioned in Yun Gee’s poem through which he dreamed he could bring his mother close. While the three figures in the foreground are rendered in a relatively naturalistic mode, the pictorial style of the painting behind them is done in radically simplified planes of color. There remain legible, however, the figure of Yun Gee’s mother “looking out the door,” as his poem states, and the forms of a tree, steamship, and train.

At the same time that it expresses Yun Gee’s sorrow over parting from his mother, the painting is a brilliant demonstration of the artist’s flexibility and his skill in using color contrasts to create both strongly volumetric forms, in the foreground figures, and complex two-dimensional designs, as in the framed painting behind them. Where Is My Mother summarizes what the beret-clad Yun Gee had achieved as an artist during his years in San Francisco. The Flute Player, done in Paris and thought to date from 1928, reflects several new developments in Yun Gee’s art and in his conception of how he wished to present himself in self-portraits. In this work his palette darkened, transitions between areas of color achieve a new subtlety, and the pictorial space, defined by the red chair and two tables, is more assertively three-dimensional than in any of his earlier paintings. Yun Gee is dressed in Western clothes, and his signature is in roman letters only, but the pipes hanging on the wall, calligraphy brushes and fan displayed in a vase, and the Chinese chess pieces in the foreground surround the artist with reminders of Chinese art and culture. These objects, as well as the instrument Yun Gee plays, demand that the viewer recognize the artist’s identity as a Chinese musician, while the painting itself demonstrates his mastery of the language of Western pictorial art.

Yun Gee’s initial reaction to Paris was love at first sight. Recalling his early days in the city, he spoke of the delight of finding himself in “the seat of an undying, eternal culture” and of his discovery of temperamental similarities between French and Chinese people, founded, he believed, on “their individualism and their cultivation of the art of living.” The exhilaration he experienced in Paris no doubt arose also from leaving behind the racist attitudes toward Chinese that seemed inescapable in the United States. But his views of Paris changed. In 1931, after taking up residence in New York, he wrote: “Paris is a liberal city. Only that liberality is limited to certain nations among which are not the United States and China.”

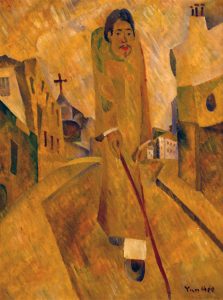

How I Saw Myself in a Dream

1929

oil on paper

19 3/8 x 15 1/8 inches

Yun Gee’s more sober view of life in Paris may be embodied in one of his strangest and most haunting paintings, How I Saw Myself in a Dream, undated but probably done in 1929, after he had been in Paris for about two years. This self-portrait shows the artist walking down and eerily vacant street of the Latin Quarter, over which a huge cross on a neighborhood church looms. A gaunt figure in a changpao or Chinese scholar’s robe and cloth Chinese shoes, Yun Gee holds a long cane, which he seems to tap the lower border of the painting. The skewed recession of the street, lined by buildings drawn in inconsistent perspective, defines an unsettling spatial setting for the walking figure. The dazzling colors of Yun Gee’s San Francisco years are replaced by an overall tonality of ocher, broken patches of green and red applied in remarkably consistent diagonal strokes that unify the surface of the canvas.

Photographs of Yun Gee from his first stay in Paris, from 1927 to 1930, show the young artist in suit and tie. But in his dream self-portrait, he chose to depict himself wearing Chinese clothes, markers of ethnic and cultural identity more immediately recognizable to a Western audience than the props in his Flute Player. He wears the same garb in another self-portrait, The Charm of Music, from 1929-30. Seated on the floor of a dimly lighted room, sharing the space with a small menagerie of sinister pets, Yun Gee peers out at the viewer while playing a dulcimer-like Chinese instrument known as the yangqin. Not only the artist’s clothes and the instrument he plays but also the material of the painting, silk, and its original mounting as a hanging scroll, are Chinese.

Knowledge of Yun Gee’s ambiguous status is Paris, where he was doubly foreign, both American and Chinese, inevitably shapes interpretations of his self-portraits, which can easily be read as expressions of his personal alienation or as emblems of a retreat into his cultural and ethnic origins. Seen within a broader context, Yun Gee’s self-portraits reflect developments in the surrounding artistic and intellectual milieu, including the emergence of Surrealism. In both his dream vision of himself walking down a Paris street, and in his self-portrait playing the yangqin, Yun Gee evokes irrational forces over which the conscious mind has only limited control-forces that André Breton’s reading of Freud had led him celebrate in the Surrealist Manifesto of 1924. Whatever their relationship to his private, interior life and his psychological state, Yun Gee’s self-portraits are carefully constructed compositions in which he self-consciously performs the role of being Chinese, presaging the dance and musical performances he would later give in New York dressed in Chinese costumes. As in other paintings of Chinese subjects from his period – the Tang dynasty beauty Yang Guifei and a series of philosophers, which appear to have won favorable responses from French critics – Yun Gee may have been giving his Parisian audience, however liberal their thinking might once have seemed to him, precisely the kind of orientalizing imagery they expected from the young Chinese artist, welcomed into avant-garde circles but still essentially an exotic outsider. This attitude, simultaneously admiring and patronizing, lingers in a comment from 1939 by the French writer, Pierre Mille: “Among the Orientals and Chinese who have come to us, Yun Gee is one of the most remarkable because his race remains evident in his work and because our Occidental gift flourishes there like a well-planted seed.”

How I Saw Myself in a Dream and The Charm of Music invite us to see the artist returning to his cultural and ethnic roots, but he appears in a different and equally authentic guise, devoid of props or unusual costumes in The Blue Yun of 1929, it’s titled taken from a signature the artist sometimes used, “Yun Gee of the Blue Five Continents.” His face shaded by a broad brimmed hat, a lighted cigarette dangling from his mouth, his wispy goatee rendered in lightly brushed strokes, Yun Gee gazes obliquely out of the painting, his look of alert skepticism more expressive than the elaborately staged self-presentations in the overtly “Chinese” self-portraits with which this painting starkly contrasts.

The Last Supper

In February of 1930, Yun Gee married the poet Paule de Reuss, whom he had met two years earlier. His new wife’s family strongly disapproved of the marriage and withdrew their support from her, leaving the couple to fend for themselves as the worsening global economic depression dried up sources of patronage for Yun Gee’s art. Leaving de Reuss in Paris, Yun Gee returned to the United States and settled in New York, where he hoped to replicate the early success he had enjoyed in France. Although he exhibited in several galleries and in shows sponsored by the Brooklyn Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art, he never made enough money to bring his wife to join him, and they divorced in 1932.

Walking Couple, a bronze sculpture based on an original in wood from 1932, recalls the Cubist-inspired work of Jacques Lipchitz and demonstrates Yun Gee’s continuing experiments with avant-garde styles after he arrived in New York. During this same period, responding to the burgeoning interest in American themes that marked the New York art world in the early ears of the Depression, Yun Gee began producing works with titles such as Houses in the Bronx, Modern Apartment, and Welders: Industries of New York. His spectacular Wheels: Industrial New York, depicts a circle of polo players – signifying captains of industry at leisure – in the foreground, while the Brooklyn Bridge and the skyscrapers of Manhattan rise in the distance. This work, along with three smaller paintings, including Modern Apartment, were Yun Gee’s entries in an exhibition of 1932 at the Museum of Modern Art titled Murals by American Painters and Photographers. Organized by Lincoln Kirstein, the exhibition was intended to promote American muralists, whose works in the mural format had been overshadowed by Mexican artists such as Diego Rivera, recently chosen to decorate the lobby of the new RCA building in Rockefeller Center.

Yun Gee had begun working on large-scale paintings shortly after his arrival in New York. In 1931 he was asked to paint wall panels for a country club in Baltimore, and in September of that year he exhibited a seventeen-foot long mural in Chinatown depicting floods that had recently struck China. It was these monumental works, as well as his entry in the MOMA mural exhibition, that prepared him for a commission to paint a large altarpiece representing the Last Supper for St. Peter’s-in-the-Bronx Lutheran Church. His patron for this commission, finalized on March 29, 1933, was one of his own students, Frances Freeman Burhop, who had joined classes to whom Yun Gee taught “New Cubism” I his apartment and led on expeditions to paint outdoors.

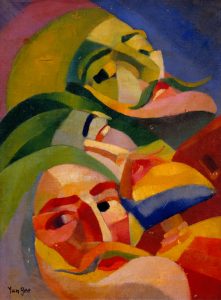

Burhop’s choice of an arch-modernist to paint such a work was a daring move, but Yun Gee had painted Christian subjects earlier in his career. My Conception of Christ, from around 1926, depicts the heavily bearded and mustachioed head of Jesus three times in starkly arbitrary colors. Read from top to bottom, the heads turn toward the viewer, gradually revealing more of Christ’s face as the dominant colors change from green, to lavender and blue, to red and pink. Yun Gee is quoted as saying that he believed that Christ “was not static,” and his synchronic sequence of three brilliantly colored heads may have been his solution to expressing this notion of dynamism. David Te-yu Wang has pointed out that Yun Gee used a similar synchronic mode in his large hanging scroll done in Paris, Resurrection. Surrounded by a nimbus of light set off against the murky sky, Christ appears as seven overlapping bodies rising upward at dawn on Easter morning, while a vulture, presumably a symbol of conquered death, perches next to the empty tomb.

My Conception of Christ

1926

oil on paper board

19 3/4 x 14 7/8 inches

The Resurrection

1929

oil on silk

67 7/8 x 30 inches

Yun Gee was not a Christian, and his interest in painting religious subjects might have stemmed from his interest in addressing the artistic challenges posed by the complex iconography of Christian art. It is tempting, however, to believe that Yun Gee may have felt a spiritual attraction to Christian themes. His poem dated April 28, 1928, “Resurrection (Ascension) Messiah,” speaks in the voice of Christ:

this I have heard

that is why I am here

this, the reason I must go

up up up to the blue

where there, everything

everything is not at all

my lost lamb ahead of me

whom I shall save . . .

Although the meaning of this poem to Yun Gee himself is a mystery, its content presages his painting of the Last Supper. In a later passage of the poem Christ addresses his disciples an order that differs an order from that found in the Gospels and may be Yun Gee’s own invention: Peter, John, Bartholomew, James (the son of Zebedee?), Andrew, Thomas, Thaddeus, Philip, Matthew, James (the son of Alphaeus?), Simon, and Judas. With the exception of the final two disciples, whose positions are reversed, this is the same order in which Yun Gee placed the figures with Christ in his Last Supper.

The reception of Yun Gee’s painting was mixed. It received some favorable critical notices, though one reviewer, writing about a study for the painting, complained that he could not tell which figure was Christ. For the members of St. Peter’s congregation, who had not formally agreed to accept Burhop’s gift, the modernist style of the painting seemed out of place in their neo-gothic structure, and the huge canvas was placed in storage at the church. A number of years later, Yun Gee dispatched a truck and two workmen to recover the painting. If it still exists, its whereabouts are unknown.

Judging from a photograph that shows Yun Gee at work on the Last Supper, the painting was about five feet high; another photograph, beneath which Yun Gee wrote the names of the figures, shows that the painting was square. Unlike any of his earlier paintings, The Last Supper demanded that Yun Gee conform to a well-established iconographic tradition, familiar to all his viewers. His key decision was to reject the format of Leonardo’s mural, the most famous image of the subject in Western art, in which the table is parallel to the picture plane; instead, following the model of Tintoretto and other artists, Yun Gee chose to show the table receding diagonally away from the viewer. In a study known through a photograph, Yun Gee experimented with a rectangular format for the composition. His decision to use a square format for the final version allowed him to create a more dramatic recession into space, pulling the viewer’s eye to the figure of Christ seated in the upper left at the head of the table bisecting the canvas. On the right an opened window reveals the rising sun and silhouetted stalks of bamboo – a Chinese pictorial motif rare in Yun Gee’s paintings.

The raised right hand of Christ is the focal point of The Last Supper, and it is from Christ’s hand that an arc of light descends to envelop the disciples, who respond in dismay to Christ’s announcement that one of them would be his betrayer. The order of the seated and standing disciples, as noted above, corresponds with only one exception to the list of names in Yun Gee’s poem of 1928, “Resurrection.” Christ’s raised right hand and his left hand held against his chest in the painting also recall lines from the poem spoken by Christ foretelling the wounds of his crucifixion: “watch my hand / also my chest.”

The features of Christ, who wears a long mustache extending horizontally from his face, recall those in Yun Gee’s My Conception of Christ, while the features and attributes of several of the disciples make them really identifiable. John, a young, beardless man, whom the Gospels tell us Jesus loved best, sits nearest Jesus, just as he does in Leonardo’s Last Supper. Thomas, the doubter, is sunk in despair, his head held between his hands. Judas, the betrayer, is a young, beardless man; although he grasps the bag holding his thirty pieces of silver in his left hand, he listens coolly as Philip, Matthew, and James address him with accusing gestures.

DaVinci’s The Last Supper

Yun Gee’s The Last Supper

The three studies for The Last Supper in the exhibition focus on three groups of figures. Inset within the larger compositional units of two of the studies are small fragments enclosed within arcs of light. The surfaces of these paintings in oil on canvas are dappled with small panes of color, many of which evoke the faceted shapes of diamonds. David Teh-yu Wang has argued that these shapes are pictorial manifestations of Yun Gee’s “Diamondism,” a complex theory that attempted to explain the cerebral, physical, and psychological dimensions of artistic creativity. Yun Gee explained Diamondism in a brochure that he had printed in the 1940s, thus joining the ranks of Twentieth-Century modernists who could claim to have founded their own “isms.” Whatever their function as manifestations of Diamondism, the studies for The Last Supper were important to Yun Gee and were exhibited at the American Art Association in New York and in group shows in Paris and Lausanne.

The unfortunate reception of The Last Supper and its obscure fate were emblematic of Yun Gee’s unrewarding years in New York during the early 1930s, when he felt he was treated not as an artist but as “an Oriental from Chinatown.” In 1936, Yun Gee returned to Paris. Forced to leave Europe at the outbreak of World War II, he lived and worked in New York for the rest of his life, plagued increasingly by illness and financial worry. Although he exhibited only rarely, the final two decades before his death in 1963 witnessed transformations in his art as dramatic as those from his early career traced by the current exhibition, and Yun Gee’s late works await fresh study and appreciation.

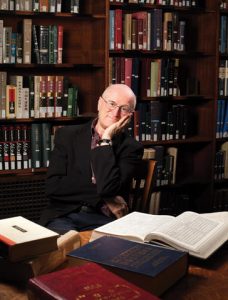

Robert E. Harrist, Jr.

November, 2001

Robert E. Harrist Jr. has published books and articles on Chinese painting, calligraphy, and gardens, as well as on topics such as replicas in Chinese art, clothing in 20th-century China, and contemporary artists such as Xu Bing. His most recent book, The Landscape of Words, which studies the role of language in shaping perceptions of the natural world, was awarded the Joseph Levenson Prize in 2010.

•BACK•