Yun Gee was a prodigy. Born in 1906, in China, he moved to the United States when he was 15 years old. It was a long way, geographically and culturally, from his birthplace, the village of Kaiping, in Guangdong Province, to San Francisco, where he joined his father, who had settled in the city there a few years earlier and established himself as a merchant. Soon Yun Gee enrolled in the California School of Fine Arts (renamed the San Francisco Institute of Art in 1961). His talent immediately manifest, he quickly found his way into a circle of avant-gardists that included the painter John Ferren and the poet Kenneth Rexroth. With these and other members of the group, Gee founded the Modern Gallery, in the heart of San Francisco. He was just 20 years old. A few years later, he launched the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club. There he taught theory as well as technique, and from his teaching emerged a style that counts as an original contribution to the history of modern painting. He called it Diamondism

(Woman With Earring)

(Woman With Earring)

From early Fauvism Gee took bright, sometimes almost dissonant colors; sharply angled and boldly faceted, the shapes of his pictorial elements have roots in Cubism. In a 1937 statement, he said, “Diamondism acts as a prism, a one-way glass. It is … not a cause but a power.” Its power is to give the surface of a subject — a face, a body — the solidity of its underlying structure. We see the architecture of a form. We also see the light-gathering, light-reflective quality of the surface itself, but not in a sedately realistic mode. Diamondism shows ordinary perceptions transformed and heightened. In (Woman With Earring), thought to have been painted in 1925, the woman’s face is built from angular patches, each a slightly different shade of blue and modulating to mauve at certain moments. This portrait is at once intimate and monumental.

(Abstract Figure Painting)

(Abstract Figure Painting)

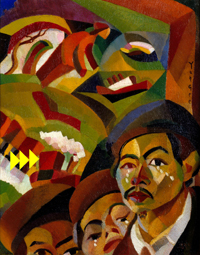

Untitled (An Audience)

Untitled (An Audience)

Cubism, Futurism, and every other modern style tended toward abstraction, and Diamondism is no exception — a point Gee acknowledged in Untitled (Abstract Figure Painting), a work from the mid-1920s. We could see this painting as a play of pure color, and yet it also presents us with the image of a human form bending intently over a canvas. Bringing us to the border where representation meets non-representation, Gee leaves it up to us to decide which reading to favor. The foreground of Untitled (An Audience) (1927), is filled by the backs of heads, rendered quasi-realistically. Half-hidden by these members of the audience is a flurry of brushstrokes we would see as abstract if it were not so clear that they indicate the object of the audience’s attention — a group of performers moving about on a brightly lit stage.

How I Saw Myself in a Dream

How I Saw Myself in a Dream

Modern styles evolve. By the end of the 1920s, Gee’s Diamondism, which put so much emphasis on surfaces, began to open onto depths. In How I Saw Myself in a Dream (1929), Gee pictures himself as a tall, spindly figure guided as much by his cane as by vision. As the street behind him recedes into the distance, the angularity of curbs and buildings softens a bit. Sinuosity has entered his art, as we see in the serpentine flow of Moonlit Stream (n.d.) and the rhythmically curving trunks in Tree Lined Street With Figure on Bicycle (n.d.). We are now in the space of reverie and dream. Light no longer shines from an external source; forms glow from within. See especially the luminous flesh in (Nude Woman Painting) (n.d.). A contrast comes into focus: Diamondism is a dispassionate vision of the world we share, whereas Gee’s later work evokes inward experience. Yet this is not entirely accurate. Where Is My Mother (1926–27), a formally brilliant example of Diamondism, was inspired by the great sorrow of Gee’s life. Because of restrictions on immigration, his mother could not follow him to the United States; after he left China, he never saw her again. Hence the tears flowing from the eyes of the figures in this painting.

Where Is My Mother

Where Is My Mother

In the late 1920s, Gee moved to Paris, where he quickly found recognition in avant-garde circles. His paintings were included in the Salon des Indépendants’ exhibitions of 1928, 1929, and 1930. Restless, he settled in New York for a few seasons, then returned to Paris. Though he showed his work frequently in both cities, he felt more at home in Paris and no doubt would have settled there permanently if the onset of the Second World War had not driven him back to New York, where he met and married Helen Wimmer. Their only child, Li-lan, was born in 1943. Two years later, they filed for divorce.

Gee’s paintings were included in many group exhibitions during the 1940s, including Portrait of America, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York. However, those were the years of Abstract Expressionism’s ascendency, and his career went into an eclipse that lasted until his death in 1963. Since then, there has been an ongoing and, in recent years, accelerating process of rediscovery. Yun Gee is now recognized as one of the most innovative artists of the 20th century.

Li-lan spent her childhood and adolescence in New York’s Greenwich Village, a neighborhood of artists and poets. After graduating from the city’s High School for the Performing Arts, she became not an actor or a musician but a painter. For her, the solitude of the studio was more congenial than collaboration, whether in the concert hall or on the stage. Throughout her life, she has been animated by a quiet rebelliousness that shows, obliquely, in the independence characteristic of her art at every stage of her career. Though Yun Gee painted several pictures of her as a very young girl, his work had no discernible effect on hers. Li-lan has always gone her own way, even when she swerved close to territory occupied by other artists — for example, in her version of Minimalism. During the 1970s, she constructed images of straight lines and right angles as severely geometric as any Minimalist box. Yet those objects are militantly non-representational, while her images picture the lined pages of notebooks and ledgers. Thus she turned the premises of Minimalism on their head.

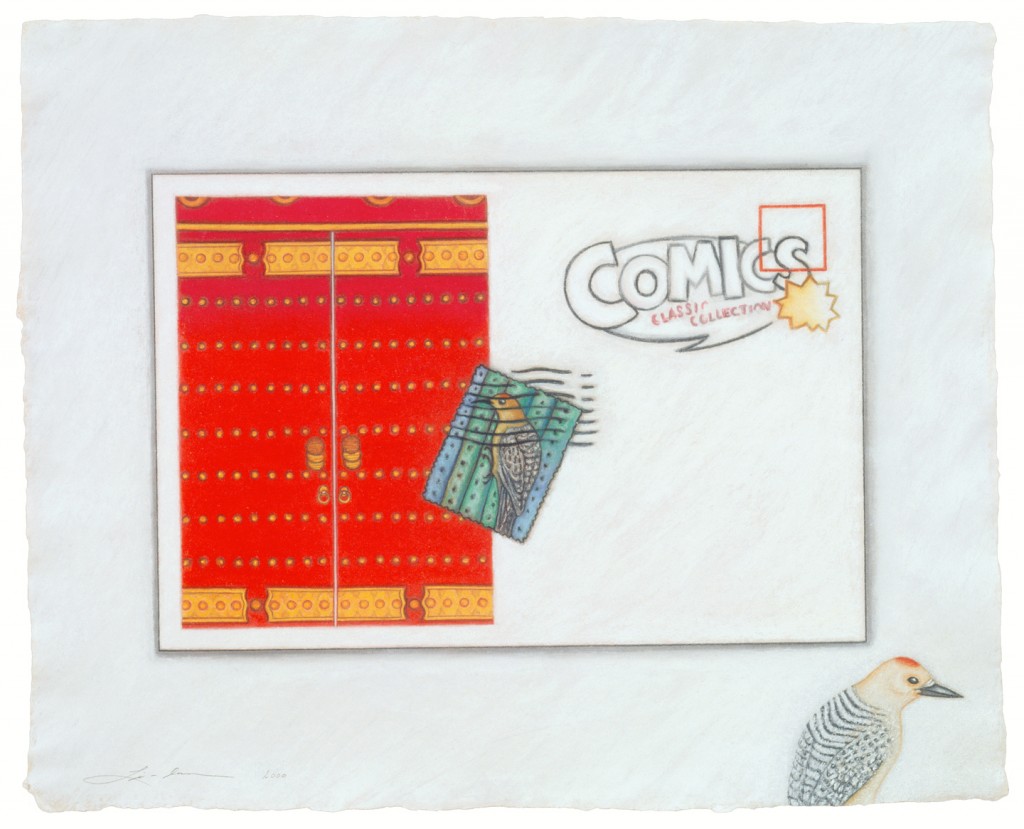

China: 30 Yuan

China: 30 Yuan

The precision of these paintings persisted as she turned to envelopes and stationery. In China: 30 Yuan (1993), she conveys the irregularities of the postmarks with astonishing accuracy. Though the artist’s display of virtuosity is fascinating in itself, the main development in this period is her introduction of new themes. Depictions of envelopes with air mail stamps symbolize communication across great distances. Scale is shifting from the intimacy of the notebook paintings to the vastness of the entire globe. As if in response to a new openness, images begin to migrate from their original places. In Comics: Classic Collection (2000), the bird who appears on a postage stamp, half hidden by a cancellation mark, reappears, unobscured and vivid, in the lower right-hand corner of the painting.

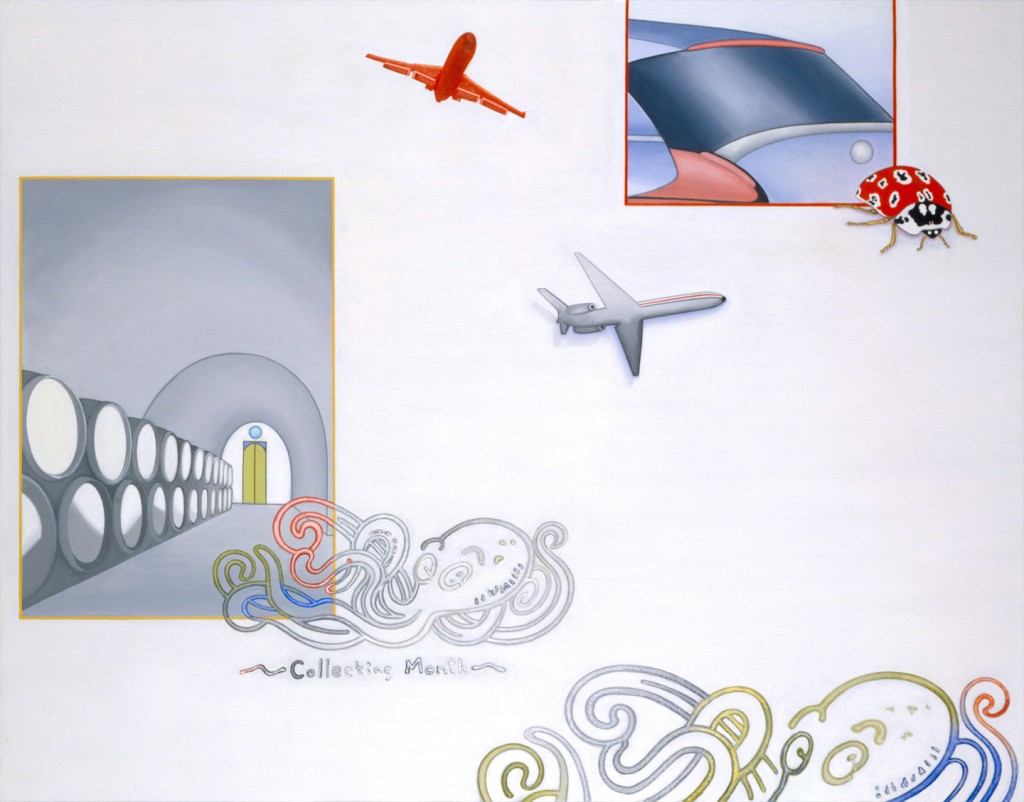

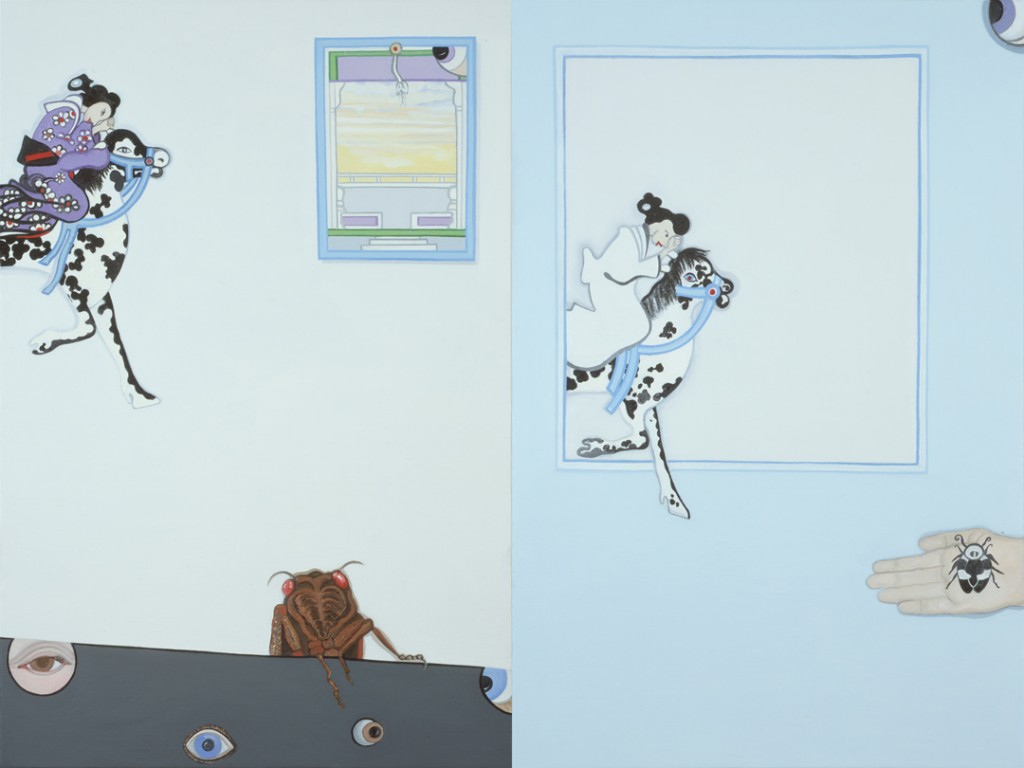

Running: Day to Night (diptych)

In Journey: Round Trip (2001) and Air Space (2002), airplane images of the kind that embellish airmail stationery fly free, through space that extends, in imagination, far beyond the frame. In paintings from the early 2000s, Li-lan began to evoke the infinite and to punctuate it with pictures of architecture’s orderly enclosures — as in Echo (2005), where a long arcade, painted in the subtlest shades of gray, slants into the depths. Running: Day to Night (2012), brings a surprise: the mode of transportation in this painting is not an airplane but a horse. The rider is a woman in a traditional Asian costume. Perhaps time had always been an underlying theme of Li-lan’s art, but now it is explicit. With this painting she marks the passage not only of hours but also of centuries, for the rider’s apparel is pre-modern, even ancient. Temporally and spatially, the scale of her art is always expanding.

Comics: Classic Collection

Life’s Cycle

Birds, frogs, horses, insects — Li-lan long presented them with meticulous exactitude. In this respect, she remained a realist, even as she dispensed with ordinary pictorial structure and thereby invited the infinite into her paintings. Every striation and spot of color marking the bird in Comics: Classic Collection is defined well enough to satisfy an ornithologist. But no handbook of the birds or the butterflies contains the winged creatures that have been appearing in Li-lan’s paintings during the past half-decade. Early stages of this evolution from scientific accuracy to imaginative freedom appear in Life’s Cycle (2014), which is inhabited by a bird with wing and tail feathers like the diaphanous fins of a goldfish. There is also an animal with wings like a griffin, a mythical beast, and a couple of insects with astonishingly unfamiliar anatomies. With her recent paintings, Li-lan ushers the cycle of life into new territory.

Flying

Dance of the Birds

A moth with a ghostly human face hovers at the center of Flying (2017). Elsewhere in this painting are abstract forms that seem to be taking on the shapes of animals — or are they escaping those shapes, to inhabit some as yet unimaginable state of being? Though ambiguities like this pervade Li-lan’s paintings of the past few years, she is not trying to mystify us. Rather, she invites us to see — and to feel — the fluidity in all things, including the means of depiction. The cardinal that perches on the right-hand edge of Dance of the Birds (2018) is rendered with a touch of her previous realism, while, just below, a cluster of non-figurative circles and curving lines resolves itself into something like a duck. Or possibly a duck-billed platypus. We needn’t settle on one interpretation or the other, for Li-lan is telling us, with her manifold images and modes of depiction, that the real is not static. It is inexhaustibly renewable, as we see in the work of an artist who has imagined for herself an unlimited range of options.

There is no end to the speculations prompted by the captivating presences that give her paintings their intense life. So we wonder how it is that, in Sharks’ Song (2018), even the shark with bared teeth looks welcoming. Why, in Dancing in the Sky (2019), does the shadow of the dancer in a white dress appear in front of her, not behind her? Questions like these pose themselves not to demand answers but to draw us more deeply into the richness of Li-lan’s art. Interspersed with the flora and fauna of her paintings are female figures in vivid robes. Dancing, playing a flute, exchanging gazes with a bird, or sitting in contemplative poses, they are surrogates for the artist. Or so it seems sensible to suppose. For they have a grace that looks like a visible manifestation of something invisible: the calmly creative energy that has guided Li-lan from the luminous accuracy of her early work to the deeply imagined, splendidly realized universe we encounter in her recent paintings.

Carter Ratcliff is a poet and art critic. His writing on art has appeared widely in journals and museums in the United States and abroad. Among his books are The Fate of a Gesture: Jackson Pollock and Postwar American Art (1996) and Out of the Box: The Reinvention of Art 1965–1975 (2000), as well as monographs on Alex Katz, Andy Warhol, John Singer Sargent, and others.