The Not-So-Still Life: A Century of California Painting and Sculpture

Excerpt from: “Before the World Moved In – Early Modernist Still Life in California 1920-1950”

As California artists began to embrace new ways of seeing in the late 1910s, still life seemed an ideal vehicle for the formal innovation and unconventional subjects that came to characterize modernism. This neglected, often unpretentious genre had the advantage of being less ideological than religious or history painting, and its boundaries could easily be stretched, as Cezanne had clearly demonstrated.

Adapting some of the stylistic modes of European modernism – Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism as well as variants of Symbolism and Surrealism, Geometric and Biomorphic Abstraction – a few bold California artists experimented with new pictorial languages. Their experiments expanded the definition of American still life beyond realistic depictions of arranged objects to avant-garde formulations. During the first half of the twentieth century their imagery became more abstract, more subjective, and at times laden with symbolic meaning. In Southern California’s “artistic dessert” innovation took hold earlier than in the north, which remained more conservative until the late 1940s.

Traditionally, a mastery of still life skills had been required before an artist was ready to work in the more complex, more elevated genres of religious or history painting. San Francisco artist and teacher Otis Oldfield carried on this tradition, insisting that his beginning students in drawing and painting produce conventional still life studies. At the same time Oldfield, who had been exposed to Cezanne and European modernist movements during his years of study in France from 1911 to 1924, made his students aware of the tenets of modernism.

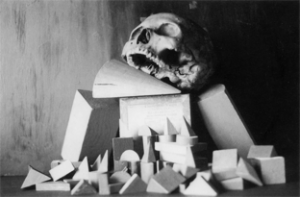

In the mid-1920s Oldfield developed his Color Zone theory to teach his students the “simultaneous contrast of color and the rapport of contrasted objects.” Inspired by the trends he had observed in Paris, including Cubism, Sychromism, Orphism, and Futurism, Oldfield demonstrated his theory with handmade blocks in many shapes and colors. Using his method, students then composed paintings by laying distinct strokes or planes of pure color directly on the canvas in methodically constructed zones based on a “nucleus key tone.” The goal was to retain the freshness and strength of unmixed color without concern for details of from. But Parisian experiments with color as the primary element of painting had led to abstraction, whereas Oldfield’s students’ paintings, like his own, were representational, not abstract. Oldfield idolized Cezanne, and his still lifes of apples or oranges embody this reverence.

Otis Oldfield ~ Skull and Color Blocks

Otis Oldfield ~ Skull and Color Blocks

One of Oldfield’s students was the talented young Chinese American Yun Gee, whose still lifes of 1926 and 1927 reflect the importance of color and rhythmic flow of forms. Yun Gee’s Skull of 1926, a small oil on paper, is a mimetically correct portrait of an actual skull from an archeological dig – an untreated skull that was not cleaned, bleached, or wired together, its jaws still askew. A photograph from the Oldfield Estate shows a still life setup with the same skull.

Although Skull suggests the influence of Stanton Mcdonald-Wright’s Synchromist work, Yun Gee could not have seen Wright’s work until 1927, when it was first exhibited at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor. And it is unlikely that he studied Wright’s 1924 Treatise on Color, because his English skills at that time were limited. The only plausible explanation for Gee’s treatment of form lies in Oldfield’s Color Zone theory. Yun Gee’s remarkable creativity allowed him to take Oldfield’s teaching method one step further to a high level of personal expression.

Yun Gee ~ Skull (1926)

Yun Gee ~ Skull (1926)

Yun Gee’s small, semiabstract still life compositions are closely related to Synchromism and Orphism with their energetic surface of irregular arcing planes, shapes, and triangular facets. Skull, art historian Joyce Brodsky observes, “unites object and color into a dynamic vortex of rhythmic intensity that almost anticipates Picasso’s skull studies of the 1940s. . . . This is no decorative synchromy but an evocation of radiant force . . . that bears comparison with the work of American painters like Arthur Dove or Georgia O’Keeffe.” While a student at the California School of Fine Arts, Gee established the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club in San Francisco’s Chinatown, where he taught classes in advanced forms of Western art to other Chinese immigrants. The term “Revolutionary” has led several scholars to suggest that the club had a radical political agenda rather than a strictly cultural one. Although San Francisco’s restrictive conditions for Chinese immigrants could have motivated a political agenda, the club was in fact formed to create an awareness of current trends in art. Its aim, said Yun Gee, was “not to cultivate merely an art of compromise, nor a safe, middle-of-the-road art, but to create an art that is vital and alive that will contribute to the development of Chinese painting technique.”

Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s most San Francisco artists continued to embrace Impressionism, Postimpressionism, and academic realism. The dominance of conservative styles was reflected in submissions to the San Francisco Art Association annuals, which typically featured just a sprinkling of modern works. The more progressive artists exhibited their work at small boutique galleries, such as the Paul Elder Gallery, Galerie Beaux Arts, and East West Gallery of Fine Arts. Private collections of modern art were occasionally shown in San Francisco during this period, but there was no bona fide venue for exhibiting modern art until the San Francisco Museum of Art (now the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) was founded in 1935. In 1926, a group of younger progressive San Francisco artists, including Yun Gee, organized the cooperative Modern Gallery in the heart of the studio quarter on Montgomery Street. Although it enjoyed the support and encouragement of established modernists Gottardo Piazzoni, Ray Boynton, Ralph Stackpole, Lucien Labaudt, and Otis Oldfield, the overarching exhibition schedule proved too difficult to maintain, and the gallery was closed in January 1928.

Patricia Trenton, independent curator, is the editor of Independent Spirits: Women Painters of the American West, 1890-1945 and California Light, 1900-1930, as well as the principal author and curator for the Irvine Museum’s Joseph Kleitsch: A Kaleidoscope of Color.

•BACK•