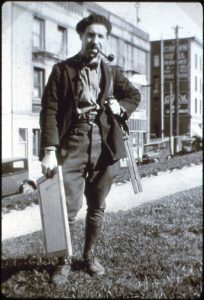

Yun Gee – San Francisco

Yun Gee – San Francisco

Among the most advanced modernist painters active in California during the 1920s, Yun Gee forged an international career that began in his native China, included two sojourns in Paris, and ended in New York City with his death in 1963. Plagued by chronic alcoholism, depression, and professional disappointment, this remarkable innovator’s story is far from a happy one. It nonetheless provides an enlightening case study of the obstacles encountered by American artists of color who aspire to full participation in the international (meaning at the time Western) cosmopolitan creative community.

The issues that Yun Gee’s career as a painter raise are multiple, ranging from the inevitable struggle advanced artists encounter as they seek acceptance for their work, to the limitations – and opportunities – imposed by race. The picture is further complicated by individual and group expectations involving responsibilities to race and community on the one hand, and concomitantly “appropriate” subjects and style on the other. As a Chinese American, Yun Gee, whatever his personal aesthetic and career goals, functioned within a complex of identity-inflected forces that many other white American artists were spared. Race is far from the only factor that informs the work and career, but it surfaces in the art of Yun Gee as a dialogue between international modernism and a powerful inclination to give visual expression to personal life experience. With this in mind, my primary goal in this brief essay is to indicate several general themes that, at least for me, emerge from a consideration of Yun Gee and his paintings: modernist personalism, race and cosmopolitanism, and eroticism.[1]

The paintings of Yun Gee are self-consciously modernist and stylistically sophisticated. But at the same time there is a strain of personalism that informs the work. In this respect Yun Gee could well bring to mind fellow artists such as Marsden Hartley, whose German Expressionist-derived modernist paintings cannot really be understood without reference to the events of his life and the longings, going back to childhood, that conditioned his experience of the world. At any rate, this autobiographical inclination is an aspect of modernity that informs the work of a number of twentieth-century artists but has yet to be fully acknowledged as a potent force within the work of many of them, including Yun Gee. Herein lies one of the alternative features that continue to expand our understanding of what twentieth-century modernism involved. It becomes clear that the forms alone do not signal modernist art. The expression of individual experience and interior life can count for as much as the influential example of avant-garde experimentation in an artist’s rearranging the visible world.

In the United States during the 1920s, but especially in the years following the 1913 Armory Show, European modernism found scores of imitators: Expressionism, Fauvism, Futurism, Surrealism, and especially Cubism. Much American art declared its modernity by “cubifying” the subject, in a form of the movement that hovered close to the surface, generally without a deep understanding of the structural and perceptual issues involved. Yun Gee’s modernism was more sophisticated, drawing upon various sources as fruitful stylistic alternatives in a focused artistic quest. The forms chosen for exploration were not ends in themselves, but rather part of an ongoing search for expressive meaning. Yun Gee’s Cubism was inflected by a personal narrative in which the “self” is revealed in the forms. This was a strain of modernism not previously acknowledged, at least within accounts of mainstream developments, to the extent it is today. Numerous artists are being rediscovered and/or reexamined as a result of post-modernist revisionism and the confessional art of the 1980s and 1990s. An expanded notion of modernism is the result, allowing a more nuanced and less exclusively formal interpretation of works of art, leading to a greater understanding of the role played by identity and life experience.[2] The insertion of self may be seen as part and parcel of a developing – and most significant – strand of modernist practice. Search for the universal within one’s individual experience is, after all, still consistent with the dehistoricizing goals of most modernist theory.[3]

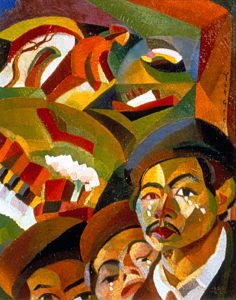

Where Is My Mother

Where Is My Mother

1926-27

Perhaps the most famous example of this personalism among Gee’s paintings is the poignant Where Is My Mother, a work that stands as a shared lament for family, friends, and compatriots left behind in China.[4] Included in the poetry section of this volume is the companion piece to this painting, the poem bearing the same title, expressing the sense of great loss not only at being separated from a mother but also in severing ties with home and country. The forms, literary and visual, are secondary, providing the vehicles for expression of deeply felt personal experience.

How I Saw Myself in a Dream

How I Saw Myself in a Dream

1929

Portrait of Paule de Reuss

Portrait of Paule de Reuss

1928

Another important example in Yun Gee’s oeuvre is How I Saw Myself in a Dream (c. 1929). The direct connection to a poem does not appear in this case. But the autobiographical impulse and sentiment behind the work is similar. Less well-known works that equally demonstrate the personalism of Yun Gee’s art include examples such as Portrait of Paule de Reuss (c. 1928), a picture of Gee’s first wife. A companion poem, The Poetess, takes on a poignancy (and even eroticism) based on their forced separation while she waited for him to bring her to the United States.

As the notion of Yun Gee as an autobiographical modernist is more fully developed, an important but as yet unexplored connection emerges. What familiarity Yun Gee had with the early work of Diego Rivera is less than clear. However, the affinities they shared in imposing a modernist cubist structure on personal and ideological themes is both evident and revealing. Yun Gee and Rivera missed one another in San Francisco by only a few years. The famous Mexican muralist arrived with his colorful and flamboyant wife, Frida Kahlo, in November 1930, by which time Gee had returned from Paris to New York. Since by then Rivera was one of the most famous artists in the world, and especially admired in the San Francisco Bay Area by Gee’s friends and associates, such as Victor Arnautoff and Kenneth Rexroth, it is virtually certain that Gee was familiar with his work. The Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club that Yun Gee organized invited Rivera to a reception at the club’s studio when he arrived in San Francisco. [5] And although there is no record that the two met, there is indirect evidence that Gee may have communicated with Rivera.

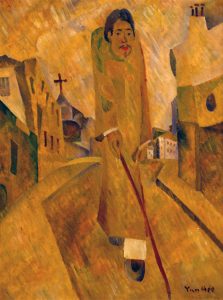

(China and Manchuria)

(China and Manchuria)

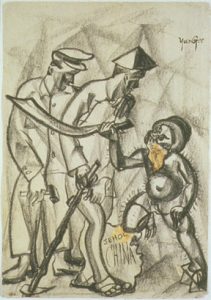

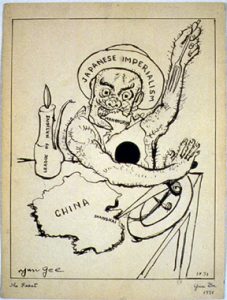

The Feast

The Feast

1931

It is tempting to think that Rivera’s well-known left-wing political sympathies, and later the anti-fascist elements that appeared in his work as World War II expanded in Europe and the Pacific, encouraged Yun Gee’s political drawings dating from about 1931 [China and Manchuria]. Gee’s political thinking could sometimes rile his emotions, as in his drawing of the Japanese invasion of China, The Feast (1931), in which a demonic figure sits at the dinner table making a meal of China. The hairy beast, with the rising sun emblazoned on his bib, wears a hat with the words “Japanese Imperialism” on the brim while chewing on a Manchuria that has been severed from the map of China placed before him. A vessel sitting on the table carries the inscription “League of Nations,” a reference to the Paris Conference peace treaty compromise in which Japan would keep Germany’s economic holdings in China and at a later date return the strategic Shantung peninsula. (The outraged Chinese delegates refused to sign the treaty. Another compromise permitted the Japanese to also keep, as a mandate from the League of Nations, the German islands in the Pacific that were used as bases against the United States in World War II.) In his political imagery, Yun Gee lacks the complexity and breadth of vision encountered in Rivera’s murals, notably Pan American Unity (1941), now installed in the Diego Rivera Auditorium at San Francisco City College. However, the personal concerns and experiences, the tendency to insert autobiography and self-revelation into a utopian or at least idealistic political statement, are to some degree shared. [6] Above all there is the willingness to appear as an actor in the painted world of the artist’s creation. Rivera just had the opportunity to do so on a far grander, wealthy-patron and state-supported, scale.

The list of talented painters who were ignored or rejected by a capricious art world is depressingly long, and it includes the names of some whose work deserves greater historical recognition. Yun Gee is solidly within this group. There are many reasons why an artist is passed over, and they remain almost as mysterious now (especially for serious artists trying to establish or revive careers) as they were then. Some of it has to do with the individual; some of it with the work. And much of it has to do with the art market and advocacy within the critical/curatorial establishment. At one time, not too long ago, it was fashionable to imagine that great art would declare itself to a receptive and grateful art world – that eventually those individuals and institutions involved in making the judgments would recognize and honor significance. The stories of artists such as Yun Gee remind us that this is not the case.

Otis Oldfield – San Francisco

Otis Oldfield – San Francisco

Every artist is vulnerable to the shifts in fashion that cultural “progress” brings. Yun Gee’s friend and teacher, San Francisco modernist Otis Oldfield, wrote to his former student letters expressing deep disappointment as he and his work were increasingly marginalized. [7] For Oldfield, as well as for Yun Gee, the promise and excitement of the Paris years – and the expectation of a distinguished career back in the United States – remained essentially unfulfilled. The disillusionment of gifted American artists such as Oldfield was real and understandable. But Gee’s difficulties were also undoubtedly compounded by issues of race. [8]

The unavoidable question is to what extent, and exactly how, did being Chinese American affect the artist’s career? Would his work have been received more generously if he had been white? Would his modernist vision have taken a slightly different form? In other words, just what is the role of racial identity in the broader picture of American art? How are we to untangle the threads that connect the individual to context in order to better understand the forces underlying creative activity and, ultimately, the art itself? Perhaps two other more or less contemporaneous American artists, George Tsutakawa in a specific way and Jacob Lawrence as a more generalized model, will bring the issue of race into focus in a way that may be useful in considering the experience of Yun Gee. Tsutakawa, a prominent Seattle fountain sculptor, taught for years at the University of Washington but kept strong connections to family and friends in Japan. He observed that in Japan his work looked very American, but in the United States the work struck many as very Asian. When asked whether he was a Japanese or an American artist, he responded, “I am neither, I am both.” [9]

At issue is one’s identity in America as an artist and on what it depends. This is a key question in connection with Gee, as it is (or was) for all artists of color despite the differences in their actual experiences. The two issues upon which the question turns are Yun Gee as a modernist, characterizing his individual accomplishment without regard to race and, second, the role of race in his career, the imagery itself, and reception of the work. Both involve his self-conception and aspirations. Who was he? Where were his loyalties? Who were his people? What were his goals as an artist, beyond the individual acts of creation? Beyond but related to this matter of the possible limits imposed by race and personal identity is an even bigger issue, at least from the standpoint of the reception of modernist art and therefore the fortunes of those who produce it. This question goes to the heart of cosmopolitanism by asking what critical or aesthetic judgment requires Asian-American artists to remain somehow “exotic” rather than being allowed to bring yet another set of traditions to the common table, thereby enriching the cultural and stylistic panoply that in fact defines modernism.

Jacob Lawrence is a kind of general model, and to my mind an instructive one despite his unique status in connection with racialized art, for a discussion of race in the United States as it affects creative activity. Although it would be a serious mistake to apply Lawrence’s experience to all African Americans, and even more so to Asian Americans and other artists of color, there seems to be a basic dilemma that many of them have had to face. First there is inescapable identity, which has typically determined, to a degree, one’s place in the white-dominated world. Along with this may come a sense of personal obligation to race, or at least some vague feeling of community solidarity. At the same time, there is the need of the individual artist to function as an independent creative spirit. It seems to me that Lawrence managed to achieve a remarkable balance between these several, often competing, forces. [10]

How did Yun Gee position himself within the inevitable limitation of this unavoidable American situation? As he encountered discrimination in Paris as well as in San Francisco and New York, the burden of racism was a discouraging and debilitating factor, one that inevitably surfaced in his work. Yun Gee sought through his art and related activities, as did Lawrence for African Americans, to provide a means for his Chinese countrymen to participate more fully in modern life and culture as found in the West. The “practical” local manifestation of this idealistic goal was primarily evident in his early efforts to promote the New National Painting through his Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club. [11] Of course Lawrence, with the legacy of slavery, had a far more difficult and socially comprehensive challenge in that regard.

Unlike Yun Gee, with his far more limited efforts, Jacob Lawrence with consistent and sustained determination dedicated his entire career to the betterment (largely through education) of his people and their community. There seems to be little evidence that such a grand ambition was ever a part of Yun Gee’s aspirations for the New National Painting and the few artists he brought together in Chinatown’s Revolutionary Artists’ Club. Richard Cándida Smith has insightfully put his finger on the fundamental difference within the context of a modernist movement, both internationally and within the United States. He argues that Yun Gee sought to be part of a global cosmopolitan movement but was excluded from full participation by being racialized. Lawrence’s participation, on the other hand, was largely the result of racialization. [12] This inverted race-based judgment made a virtue of the faux-primitivism many critics and the market embraced in his depictions of Harlem and the black experience. In effect, Lawrence’s colorful and simplified forms were accepted as the appropriate modernist design devices for the depiction of Negroes in America. Despite his atypical success, and the esteem in which he is now held, Lawrence and his work remained (favored) representatives of difference, the quality that American race-consciousness consistently emphasized over legitimate aesthetic and conceptual considerations. This seemed also to be the fate of many less prominent artists of color, at least in terms of their posthumous reputations. The question of just how Yun Gee fits into this pattern of racial definition, exclusion, and typical neglect still leaves ample room for further study.

San Francisco Street Scene with Construction Workers

San Francisco Street Scene with Construction Workers

1926

Having acknowledged the differences between these two artists, it is still interesting to look at the Chinatown street scenes of Yun Gee with Lawrence in mind as a provocative and possibly revealing contemporaneous comparison. Anthony Lee has described these early San Francisco paintings in terms that emphasize the personal aspect, not only Yun Gee’s sense of a discreet community in which he played the flâneur, strolling up and down the steep streets of the policed Chinese quarter, but more tellingly the sense of the city beyond in which he and other residents were unwelcome. According to Lee, paintings such as San Francisco Street Scene with Construction Workers (1926), display “Gee’s growing sense of himself on Chinatown’s streets” and an awareness of the restricted freedom his new circumstances in America imposed. Furthermore, Gee’s depiction of a man strolling with pipe in mouth in San Francisco Street Scene with Construction Workers “probably is a stand-in for the painter himself.” [13] This personal identification with Chinatown and its inhabitants, and the implied conditions resulting from racism and poverty, suggest an art – like that of Jacob Lawrence – that transcends an exclusive or (at least in Lawrence’s case) even primary interest in the formal and expressive experiments of early twentieth-century modernism. In neither case are the depicted scenes picturesque, nor are they simply urban landscapes put to the service of the perceptual or structural investigations of modernist art. They are painted reports from ghettos in American cities in which the reporters have shared the experiences of those who have been subjected to the disadvantages, inequities, and indignities imposed by a racist society. These social and autobiographical qualities, this personalism, introduce compelling reasons to reconsider and possibly adjust the identifying features of Yun Gee’s modernist persona.

The great stylistic variety of Gee’s art is immediately striking. From his earliest recorded career, as a student at the California School of Fine Arts, Yun Gee seems to have been aware of advanced European painting, the features of which he freely incorporated into his own work. In fact he did so more than any of his San Francisco contemporaries who come to mind, including his teachers, Gottardo Piazzoni and Otis Oldfield. David Teh-yu Wang speculates about the various sources from which the young artist drew – what he may have seen – and the impact of these models on his work. The Oakland painters who exhibited together as the Society of Six are mentioned as probable influences. And they were indeed among the most progressive artists working in the Bay Area during Gee’s presence there. But their decorative post-Impressionist styles were not as radical as Gee’s student works such as Chinese Musicians (1926-27), Man Writing (1927; plate 7), or even Street Scene, San Francisco (1926). What set Gee apart was not only his stylistic receptivity but also his structural use of color. His two portraits of Otis Oldfield, Portrait of Otis Oldfield (1927) and Head of a Man (1926-27; plate 1), are accomplished cubist paintings in which blocks and planes of color interlock to form a unified expressive whole. The same may be said of the portraits and landscapes done in San Francisco and during the subsequent Paris years, as in Mrs. Salinger in Paris (1927).

Untitled (Mrs. Salinger in Paris)

Untitled (Mrs. Salinger in Paris)

1927

This practice has been credited to Oldfield’s “color zone” teaching program, which no doubt was the case. [14] Furthermore, this direction was reinforced by contact with Orphism and especially Synchromism in the 1927 joint exhibition of Morgan Russell and Stanton Macdonald-Wright. [15] The direct impact of these sources is indeed evident in the paintings of this period. However, some of the works from around 1927 are more faceted and cubified than is consistent with the Synchromist example, suggesting analytical cubist influence.

Another likely source quite directly displayed is German Expressionism, examples of which Gee could well have seen at Galka Scheyer’s Blue Four exhibitions starting in 1926 at the Oakland Gallery. Portrait of a Woman (undated), with its highly arbitrary, expressive color, brings to mind Alex Jawlensky and even the Fauve-period Matisse. Another possible source for this tendency may have been Edward Hagedorn, a fellow student at the California School of Fine Arts. Hagedorn’s German Expressionist-inspired work was all but unique in the Bay Area at a time when Cubism and, a bit later,Surrealism were the major European influences. Like Yun Gee, Hagedorn himself is only recently receiving serious attention. But the possibility that they crossed paths at that time is intriguing.

All of this is, of course, speculative. Without documentation of the sort that the following sections of this book are bringing to light, we cannot be sure just what the artist saw or did not see, other than the work of his teachers. Certainly Oldfield had an impact, as did Piazzoni, to a lesser degree. Oldfield’s method does seem to have been dutifully incorporated into Gee’s student work. However, no explanation has been provided to explain Yun Gee’s early ability to go beyond these sources, making them his own. Oldfield’s actual paintings rarely kept pace with his theory. Were there other factors, even available models, that contributed to the sophistication of Gee’s youthful work? It may well be that Yun Gee’s modernist sensibility and left-leaning political views were established, as Lee suggests, in China. [16] And this is particularly possible if we recall that modernism is more an attitude, a way of seeing the world, than a prescribed menu of styles and formal devices.

Yun Gee’s determination to reinvent himself as a modernist painter is evident in the burning of about two hundred of his early works.[17] In this act we are reminded of similar obliterations of the past by David Park and John Baldessari, both of whom torched a significant body of early abstract painting. Still, many writers on Gee have tended to focus on his Chinese background, looking to ethnic identity and experience in China for answers about his art as it diverged from Western modernist models. As was the case with George Tsutakawa, there seemed to have been a determination to tease out the “oriental” qualities in Yun Gee’s work. [18] And there is no question that he, again like Tsutakawa, saw himself as a bridge between two cultures and artistic traditions. Perhaps he saw modernism as a means to move beyond both without rejecting either, a strategy for his own survival in a new and not always hospitable environment. Certainly his founding of the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club signaled a desire to enhance the lives of overseas Chinese by introducing them to progressive art and thinking. [19] It was as if a kind of redemptive progress could be achieved through art, a belief entirely consistent with high-modern precepts.

In October 1926 Gee had a solo exhibition at the Modem Gallery in San Francisco. Of the seventy-two paintings on display, most of them reportedly sold. This would count as an extraordinary debut for any artist at any time. For a Chinese American it was almost unimaginable, or so we would assume. But during his early career Yun Gee often met with this kind of reinforcing acceptance and support, in Paris and New York as well as in San Francisco. The show put Gee at the forefront of the San Francisco art world and also provided him an opportunity to go to Paris and study, a goal of many American artists at that time. While in Paris he had multiple shows, and that at the age of twenty-three. This seems close to unprecedented for a young foreign artist. Even Picasso had to wait longer for that kind of attention. What is the explanation? One is tempted to ascribe this interest, at least in part, to exoticism and a fascination with the “other.” According to Wang, “Gee’s work was regarded and welcomed [in Paris] as an embodiment of Oriental mysticism.” [20]

In his later accounts of life in Paris, Gee recalled almost daily visits to the Louvre:

When I visited the Louvre day after day, the masterpieces there spoke to me in a language which was neither French nor Chinese but which transcended time and place. Here was something universal [emphasis added] which had meaning for every man regardless of race or state. A painting by Cézanne or Courbet became as close to me as any of the scrolls by the Chinese masters with which I was so familiar. And I realized that East and West were not so far apart, for in their finest creative effort, there was something very much akin. [21]

This is a revealing statement in terms of the artist’s self-conception as an exponent of up-to-date European-derived modernist art, but still determined not to abandon Chinese style and tradition. This actually is a familiar predicament in which emigrant groups and individuals find themselves in the United States. Again like George Tsutakawa, Yun Gee found a way to proudly acknowledge national origin while demanding independence to develop as an artist. In this respect and others, Yun Gee displays the internationalist that he aspired to be as an antidote to the discrimination he experienced as a Chinese American and the eventual disappointments he encountered as an artist.

Yun Gee’s art and life seem to be stamped with longing and desire, always seeking something beyond what was at hand. Perhaps at the bottom of it all was a desire to be fully accepted into the society in which he lived. How he felt about the art community in which he operated is not documented. He may have realized that there was not much he could do about his reception in the art world and, especially, the wider New York social milieu. But there was one area in which he felt that he could exert some control, and that was in his relationships with women. [22] He was married twice, first to the poet Paule de Reuss and then to Helen Wimmer, both for only a few years. A third domestic relationship (with Velma Aydelott) lasted for a longer time. Each woman was white, and it is likely that Yun Gee was attracted to and enjoyed relationships with other white women along the way. (It must not be forgotten, however, that for most of those years Chinese women were usually barred from entering the United States by the Chinese Exclusion Act.)

Linda Darnell

Linda Darnell

1951

The paintings may present some evidence of a need for the validation provided by women. At any rate, in a subtle way, this ever-present enthusiasm of his life occasionally comes to the surface (literally) of his canvases. The nudes alone do not make the case, but some of the portraits suggest more than a detached, professional encounter. The Sunbathers (1932), which depicts nudes together on a New York City rooftop, may result from a situation Yun Gee observed; but it is more likely that the scene is a product of his imagination, a stimulating fantasy that was constructed to be realized only through art. Although admittedly speculative, this may also apply to his correspondence with film actress Linda Darnell, whose portrait he painted twice, the first in 1950 and the other a year later. Judging from photographs, the works are uncharacteristically glamorous and slick – a marked stylistic departure – and present a romantic and frankly sexy image of a movie star. This attraction to Hollywood and the romance associated with films could well bring to mind Joseph Cornell and the gentle longing that characterizes his otherwise surrealist art. The mostly long-distance infatuation with this well-known actress meant a great deal to him. And perhaps it is not going too far to suggest that it also meant a great deal to his own self-image as an effective player in the cosmopolitan game, whether as an artist or as a lover of women, at a time when his career and personal life were unraveling. [23] Among the works that (always subtly) point to that aspect of Yun Gee’s autobiography is Modern Apartment (c.1932), in which two abstracted figures, seemingly women, interact within a vaguely cubist framework. We have no idea what is going on, but an affectionate and sensual moment is evoked.

A strain of autobiographical self-revelation reappears in different forms throughout Yun Gee’s work. And this appears to be the nature of Gee’s modernist art. The life does not determine the very effectively deployed modernist forms; but the forms are drafted into service as a way to control and manage an unruly world that promises more than it delivers. The way to successfully accomplish that, as Yun Gee and a score of other gifted artists discovered, is to bring words and pictures, poems and paintings, together to express a vision of how our lives, and the people who touch them, should be perceived, remembered, and – in some cases – honored. This personalism is one of the features that gives the modernist art of Yun Gee its distinctive character, its unique and very touching voice.

Paul J. Karlstrom, former west coast regional director of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, is the editor of On the Edge of America: California Modernist Art, 1900–1950 (UC Press) and a co-editor of Asian American Art: A History, 1860–1970. He is coauthor of Turning the Tide: Early Los Angeles Modernists, 1920–1956 and author of Raimonds Staprans: Art of Tranquility and Turbulence. Most recently Karlstrom wrotePeter Selz, Sketches of a Life in Art (UC Press).

Notes

- Fortunately we do not have to start from scratch with Yun Gee. There are several important studies, notably those of Joyce Brodsky and especially Anthony W. Lee, that provide a solid basis for further work. See Brodsky’s The Paintings of Yun Gee (Storrs, Conn.: William Benton Museum of Art, University of Connecticut, 1979) and Lee’s chapter on Yun Gee, “Revolutionary Artists,” in his Picturing Chinatown: Art and Orientalism in San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001). Several friends and colleagues have been extremely helpful to me in bringing this essay into its present form. In this regard, I would like to especially thank Richard Cándida Smith, Mark Johnson, Li-lan, Anthony Lee, and Gordon Chang. Their readings and comments helped me to better deal with many of the difficulties encountered in a necessarily speculative approach to a complex subject that turns on questions of race and personalism in modernist art.

- See the author’s study of Jacob Lawrence in Peter Nesbett and Michelle DuBois, eds., Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2000). The idea of an alternative, non-mainstream modernism reflecting and emphasizing life experience is further expanded in my “Modernism Through a Wide Angle Lens,” in American Modems: 1900-1950, ed. Francesca Rose (Giverny, France: Musée de Art Américain Giverny, 2000). This essay is available on the Museum’s website at www.maag.org.

- 1 have the insights of Richard Cándida Smith to thank for the formulations of these specific observations on personalism within the framework of modernist cosmopolitanism. He has also suggested that eruptions of personalism among progressive artists may have had a particularly strong presence in California, as for example in the work of Rex Slinkard and Mabel Alvarez. E-mail to the author, 10 March 2002.

- The U.S. Chinese exclusion policies of the time allowed qualified working men to enter the country but not female family members. The situation for Yun Gee was typical. For an account of the difficulties faced by Chinese and other groups in this respect, see Judy Yung, Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995).

- See Lee, Picturing Chinatown, 201-6.

- For discussion of Yun Gee’s politics, with an implied comparison to those of Diego Rivera, and his hopes for the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club, see Lee, Picturing Chinatown, 216-19. Lee also points out that, although Gee found himself in the company of some of the most active pro-Communist individuals in the San Francisco cultural world, the very people who attached themselves closely to Rivera, he never himself joined the Communist Party or adopted doctrinaire Marxist views.

- Otis Oldfield’s letters to Yun Gee are in the collection of Gee’s daughter, Li-Ian. As best as can be determined, only one response is preserved in the papers held by the Estate of Otis Oldfield. Conversation with Oldfield’s daughter, Jane Blatchley, April 2002.

- Jane C. Ju, “In Search of Yun Gee, the Chinese, American, and Modernist Painter” in The Art of Yun Gee (Tapei: Tapei Fine Arts Museum, 1992), 57.

- Video interview conducted by Mayumi Tsutakawa, Kyoto, Japan, 1988. Produced by Paul Karlstrom and directed by Ken Levine for the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art. A twenty-eight-minute edited version (Karlstrom and David Bolt, Miramar Productions) is entitled George Tsutakawa: An Artist’s Pilgrimage.

- See my essay in Nesbett and DuBois, Over the Line, 229-45. Each contributor to this anthology who dealt with social context had to acknowledge the role of race in the unfolding of Lawrence’s career.

11 See Lee, Picturing Chinatown, 216-18.

- E-mail with Richard Cándida Smith, 10 March 2002.

- For Lee’s descriptions of Gee as a stroller or flâneur in Chinatown, and the contribution of that experience to his paintings, see Picturing Chinatown, 228-29, 233.

- See David Teh-yu Wang, “The Art of Yun Gee Before 1936,” in The Art of Yun Gee.

- For an account of the 1927 Stanton Macdonald-Wright/Morgan Russell exhibition in San Francisco and a discussion of Wright’s color theory, see Will South, Color, Myth, and Music: Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Synchromism (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Museum of Art, 2001).

- Lee, Picturing Chinatown, 211-13.

- As reported in several documents, including “Yun Gee Speaks His Mind,” an essay included in this book.

- Despite their deep involvement in and sophisticated appreciation of Western modernist art, both Gee and Tsutakawa incorporated features of Chinese and Japanese art, respectively, in their own work and occasionally in details of their dress and other aspects of their lives. In so doing they seemed to be inviting or at least allowing an association with Orientalism, a position that could be viewed simultaneously as strategic, in terms of establishing a market niche (that apparently worked to Yun Gee’s advantage in Paris), and authentic in its acknowledgment of the links to heritage and early training. In other words, identity emerges as an operative factor.

- For the specifics of how these idealistic goals were to be accomplished see the descriptions of the objectives of the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club and of Yun Gee’s politics in Lee, Picturing Chinatown, 216-19.

- Wang, “The Art of Yun Gee Before 1936,” 22.

- From “East and West Meet in Paris” (1944), an essay included in this book.

- Objections that all heterosexual men love women (a debatable point), and that depicting the female (or male) nude is never a neutral activity, should not disqualify this line of inquiry in individual cases where desire seems to play a role in the selection of subjects and the creation of images. See the author’s “Eros in the Studio” in Sounds and Gestures of Recollection: Art and the Performance of Memory, ed. Richard Cándida Smith (New York: Routledge Press, 2002). What does matter to understanding both the art and the artist is the degree to and manner in which eroticism is permitted to come forward, contributing to (frequently inadvertent) self-portraiture. Again, Marsden Hartley is a compelling American example of the fusion of desire and modernist form, at least suggesting one way to approach Yun Gee and the complexity of his creative situation. Modernism is a language as well as a set of attitudes about the world and our place in it. What is important in individual cases is how the language is deployed and to what ends.

- Author’s conversations with Li-Ian in June 2001 and 14 February 2002. In the second conversation, Li-Ian reported that she recently was contacted by an elderly couple in Florida, Joseph and Salvadora Imperial, about her father. According to Mr. Imperial’s account, Yun Gee discovered his wife in a thrift shop in New York and asked her to pose. He admired her high cheekbones, apparently finding them similar to those of Linda Darnell. The woman agreed to “sit in” for the actual subject of the portrait on the condition that her husband accompany her. The couple found him “a gentleman” and “very kind.” They also commented that he was always offering to make them boilermakers. This seemingly affectionate memory portrait suggests another, contrasting side to the less happy picture of Yun Gee’s last years while at the same time alluding to the alcoholism that contributed to his death.

•BACK•