After leaving his village near Canton, China, and arriving in the United States in 1921 when he was 15, the poet and painter Yun Gee (1906-1963) enrolled in the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) and quickly came under the sway of American modernist teachers there, such as Otis Oldfield, a creator of Cézanne-inspired canvases. Prompted by developments in China under the New Cultural Movement, which called for an art that expressed both modernity and the national character of the recently established Chinese Republic (1911-49), Gee sought to develop a style of Chinese painting that would incorporate the progressive esthetic resources of the Western avant-garde (he founded the Chinese Revolutionary Artists Club in San Francisco, where he taught classes devoted to this program).

Despite that artistic mission, the canvases shown at Marlborough from his early years seem largely to draw from the by-then-familiar styles of Cézanne and early Cubism. Two highly finished oil-on-board portraits, Head of a Man and Female Portrait (both from 1927), for example, are composed of patches of color that both for a facetlike skein over the surface plane and convey shadow and volume through the alternation of cool and warm hues.

At one point Gee lived in Paris among Gertrude Stein, Paul Valéry and other denizens of the city’s avant-garde. He then settled in New York, where, in the early 1930s, he created what may have been his most original work: canvases with motifs organized so as to radiate around a single point or overlap as they ascend the picture plane in a way that suggests the composition of traditional Chinese painting. Sun Bathers (1932), for example, shows a group of angular nude women on beach chaises – in poses reminiscent of those in Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon – in a flattened composition within which they seem to rotate pinwheel-fashion around a central post. Another canvas of the same year, Merry-Go-Round, displays a rotation of carousel horses around a central axis, but the circular platform has been tipped up – as in a Cubist still life – to be nearly parallel to the vertical picture plane. These two works, along with a third, were included in a significant exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1932, “Murals by American Painters and Photographers.”

Untitled (Oil Study for Wheels)

Untitled (Oil Study for Wheels)

1932

oil on canvas

29 x 24 inches

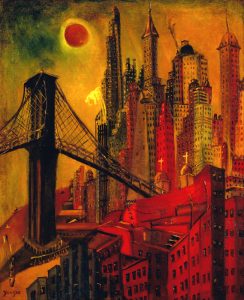

The most striking work in the show at Marlborough was the 1932 [Untitled (Oil Study for Wheels)], a painting that suggests less of the European avant-garde and more of the influence of American Regionalism and the Ashcan School. In it, grubby tenements, church domes, an imposing bridge, soot-spewing smokestacks and soaring skyscrapers are all pressed together in a densely packed mass below a bright orange and green evening sky. If such works suggest that Gee had partly relinquished his aim of integrating Western and Chinese modernism, his commitment to Chinese painting survived in a series of delicate ink and gouache drawings of flowers from around 1940. Here, the work’s ostensible pictorial subject is less significant than its graceful and self-assured calligraphic line, and the expressive power of that line’s gesture, speed and movement within the paper’s empty field.

•BACK•