Lucien Labaudt – standing, far left – with Otis Oldfield (center with pipe in hand) and Diego Rivera, sitting on left.

San Francisco, 1940

Lucien Labaudt was a painter, muralist, costume and set designer. He also ran a commercial art school called the California School of Design. After his death in 1943, on assignment as a war artist correspondent, his wife, Marcelle Labaudt, established the Lucien Labaudt Art Gallery in San Francisco, California. She specialized in giving younger or relatively unknown artists their first exhibitions and operated the gallery until 1980.

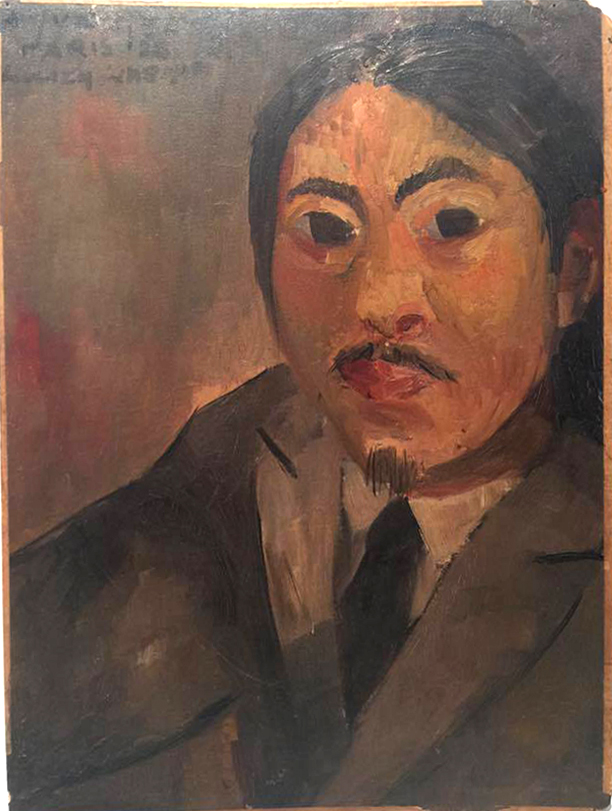

Portrait of Yun Gee by Lucien Labaudt

Portrait of Yun Gee by Lucien Labaudt

1928

Paris

![]()

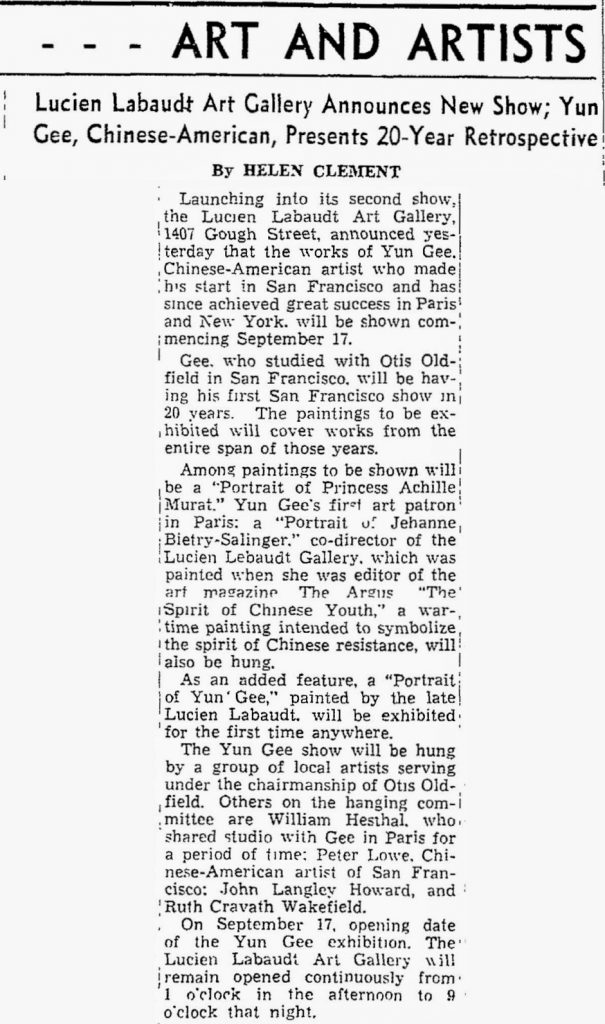

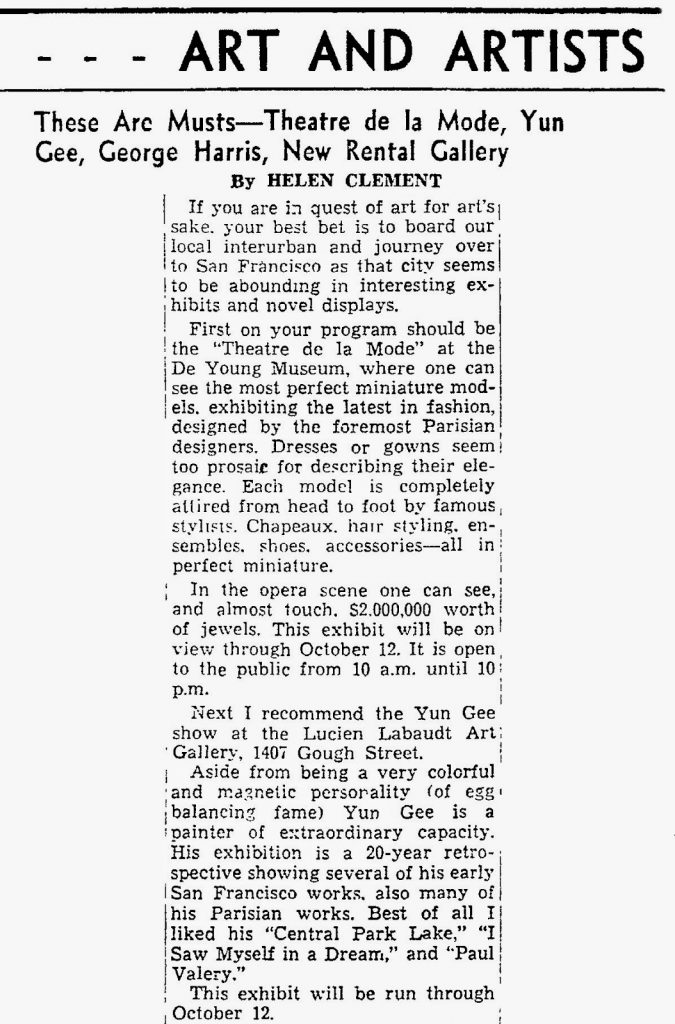

Oakland Tribune 1946

Oakland Tribune 1946

![]()

Archives of American Art Journal

Volume 24, Number 4 | 1984

West Coast

by Paul J. Karlstrom

The final quarter of 1984 saw the successful completion of two substantial pieces of West Coast business initiated a decade earlier. Certainly the most significant of these for the Archives national program, and gratifying for those of us who worked so many years toward its establishment, was the official opening of the Southern California Research Center. The November reception celebrating this event publicly marked an extremely important realignment of Archives activity in the Far West, one which has already enhanced our effectiveness as a collecting institution and which now will further extend our service to researchers in this region.

The second venture that was started in 1974 was the gathering of the Lucien Labaudt Papers. Labaudt, a French painter and dress designer who emigrated to San Francisco in 1910, is more important to the art history of the Bay Area than his somewhat faded reputation today would lead one to believe. Through Labaudt’s extensive papers, the attentive researcher gains a remarkably complete and illuminating picture of art activity in San Francisco from the teens through the war years. Rich in photographs, correspondence, sketches, and other useful documentation, the earlier Labaudt gifts have been described in previous Journal reports (see especially 1975, 14:4).

Labaudt’s close friendships with other artists, including Post-Surrealists Lorser Feitelson and Helen Lundeberg in Los Angeles, emerge in letters that help trace professional relationships and affinities in California at the time. His prominent role in the artist community is made clear by his organization of the artists’ balls, and his Bohemian Club activities. It is, however the close connections with French modernism, the art and the artists themselves, that make Labaudt and his papers so intriguing.

Labaudt’s true relationship to modernism, and by extension that of the broader San Francisco art community, was at best problematical. His own brand of Cubism was rather mild, if not thoroughly conservative. Judging from his work, he would seem an unlikely candidate for the role of a leading West Coast source and conduit for advanced ideas in the 1920s and 1930s. Nonetheless, he seems to have occupied jus that position, primarily if not entirely because of his contacts with artists in France, including Matisse, Léger, and many others of lesser stature. Indeed, his French connection led directly to the School of Paris and no doubt provided San Francisco with a degree of international involvement that it would not otherwise have enjoyed at the time.

Labaudt was not the only artist living in California, native or foreign-born, who was familiar with the developments in Europe and was closely identified with the modernists. A few had actually been on the scene in France and – most notably in the case of Stanton Macdonald-Wright – had even been direct participants. Anita Delano, a colleague of Wright’s and founding member of the UCLA art department, is another Californian whose correspondence in the Archives reveals a cordial and mutually stimulating relationship with artistically progressive Europeans, in this case Sonia and Robert Delaunay (see Journal 1975, 15:3). But nowhere, so far, is this somewhat unexpected phenomenon, a serious professional exchange between Paris and the American West Coast, documented as thoroughly as in the papers of Lucien Labaudt.

In this respect, the highlights of the first donations of Labaudt papers were communications from Matisse after his 1930 visit to San Francisco, during which Labaudt apparently serves as his host and, most likely, interpreter (see Journal 1975 14:4 and 1976 16:2). Several years earlier Labaudt had provided his fellow San Franciscans with an opportunity to see a selection of contemporary French art at first hand. Evidence of the exhibition of the École de Paris, held at the East West Gallery in late 1928, survives in the form of correspondence and a few clippings and photographs in the final group of Labaudt papers. Apparently Labaudt was the chief organizer of what one published account called “the first group of modern French paintings ever sent for a nation-wide showing.” Labaudt spent the summer of 1928 in Paris making his selection of works by younger as well as established French painters. There are in the papers a number of letters documenting the development of the exhibition and the collaboration of participants such as André Lhote, who wrote on August 10, 1928 to Labaudt:

. . . What is happening with our exhibition? I could not find my two canvases by Vlaminck. . . . However, I sent works by Picasso, Rouault, Braque, Derain from my collection, brought two Mouillet, one Simon Lévy, replaced Mlle [illegible] who had nothing, by Mlle Nora Vilter, same school, asked Gleizes and Delaunay again. Unfortunately, the former wrote me that he was in the countryside and that he knew no one in Paris to make the selection in his studio. has Delaunay, to whom I particularly wrote, sent? He did not answer me. If nothing happens, you could ask Léger.

In any case, write to tell me where you are with it and if you are satisfied with the participants. [Translation by Thierry d’Allant]

Lhote, described by a local reporter as “one of the leaders of the post-Cezanne movement in France,” was singled out for particular praise, as were other “famous moderns in Paris today” such as Marcel Roche and Oudot. Roche’s quite conventional reclining nude seemed to be a unanimous favorite of the San Francisco press. Picasso, on the other hand, fared less well. According to the critic Jehanne Bietry Salinger, “It was perhaps appropriate to have included one of his simplified cubistic experimentations that ‘retails’ for several hundred dollars. But, honestly, it is not worth a cent to the genuine art lover who . . . wants now to look at pictures.” Without a catalogue or checklist of the exhibition it is difficult to reconstruct contemporary French art as selected by Labaudt or to determine how successful he was in seasoning the conservative with more radical examples. Nonetheless, this exhibition must have had an impact on San Francisco and the other cities to which it traveled (on the West Coast, Portland and Los Angeles). The nature and extent of its influence would be a question well worth pursuing as part of a broader study of early modernism in California. The Lucien Labaudt Papers, now complete at the Archives, will be a resource essential to such a study.

The Northwest Oral History Project, underway a mere two rather than ten years, was also being brought to conclusion during this final quarter of 1984. The project, modeled on the earlier California Project and skillfully coordinated from Seattle first by Sue Ann Kendall and then by Barbara Johns, officially concluded at the end of the year. The project office at the Seattle Art Museum will be closed early in 1985 and transcripts of the thirty interviews created will be deposited at the University of Washington and Oregon Historical Society. The most recent transcripts prepared were of interviews with Alden Mason, Maurine H. Roberts, and Pietro Belluschi.

•BACK•